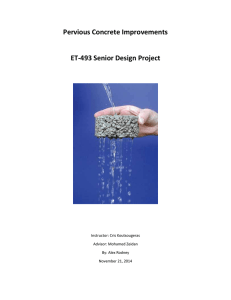

ForConstructionPros.com, MD 11-08-07 Pervious Concrete FAQs

advertisement

ForConstructionPros.com, MD 11-08-07 Pervious Concrete FAQs Green Building Philip Kresge, National Ready Mixed Concrete Association Pervious concrete is not new. Studies show that pervious concrete was first used in 1852. However, pervious concrete is enjoying a new popularity, to the point that pervious concrete pavement is the hottest topic in today's sustainable development design community. As a senior director of national resources for the National Ready Mixed Concrete Association and a member of the NRMCA's National Accounts promotion program, I have given numerous presentations on pervious concrete. These seminars have been attended by architects, engineers and specifiers as well as representatives from local and state regulatory agencies. Nine out of 10 requests I receive are for information regarding some aspect of pervious concrete. While nearly everyone understands the concept of pervious concrete and its contributions to reduction of stormwater runoff and pollutant removal, I am continually asked the following questions: "Where has pervious concrete been used? How does pervious concrete hold up to freezing and thawing? What about clogging? Does my state's environmental regulatory agency accept/approve pervious concrete for stormwater management?" In short, the answers are, "everywhere, very well, no problem and depends." But you deserve better answers than these, so let me address each of them separately. Where has pervious concrete been used? Pervious concrete pavements have been identified dating back to 1985. There may be older existing projects still waiting to be identified, though. The confusion is that back then the product was known by such names as no-fines concrete, enhanced porosity concrete (EPC) and even "popcorn concrete." The NRMCA is in the process of compiling a national database of pervious concrete projects. Of the over 250 projects currently listed in the database, 60 percent are located in the Southeast United States, with the majority being in North Carolina. Another 20 percent are located in California. The remainder is spread across the country and includes northern regions such as Pennsylvania, Ohio, Vermont and Minnesota. The projects vary in size and function and include sidewalks, cart and walking paths, driveways and even local streets. The lion's share, however, are parking lots. This is not surprising since it is where pervious concrete can best provide its most desirable benefits of reducing quantity and improving quality of stormwater runoff. The sizes of these lots range from as small as several parking spaces to projects of one or more acres. The largest site in the database is a 7-acre parking lot in Westminster, Md. Additionally, a 71⁄2-acre project is soon to be completed in Williamsburg, Va. The fact that most of these pervious sites are located in more temperate climates can be attributed to the apprehension that spawns our second inquiry. The freeze-thaw question? Many design professionals have the initial perception that, because of its porosity, pervious concrete would have little or no freeze-thaw durability. And yet, it is actually the porosity that accounts for pervious concrete's ability to withstand severe cold climates. Due to the average 20 to 25 percent void structure of pervious concrete, stormwater passes directly through the pavement and into the aggregate subbase and the subgrade below. The pavement itself is rarely in a fully saturated state. In the event that there is moisture present at freezing temperatures, the void structure of the pervious concrete provides ample room for expansion, minimizing the undue pressures that would normally be exerted on the concrete. Researchers at Iowa State University recently completed a study to develop an optimum cold weather mix design for pervious concrete. Numerous concrete mixes, with varying chemical and mineral admixtures, were subjected to freezethaw testing per ASTM C 666, Standard Test Method for Resistance of Concrete to Rapid Freezing and Thawing. The samples were fully saturated and experienced four to five freeze-thaw cycles per day for a full 300 cycles. Results of the testing showed that the inclusion of a small amount of fine aggregate, as well as air entraining admixture, provided the best freeze-thaw durability with less than 2 percent loss of mass after 300 freeze-thaw cycles. The NRMCA conducted a field study of 10 pervious concrete pavements, ranging from 2- to 13-years-old, in various freeze-thaw climates. The most moderate climate in the study area experienced an average of 50 freeze-thaw cycles per year while the most severe averaged 210 freeze-thaw cycles, with an average below freezing for 60 days. The results of the study (available at www.nrmca.org) show pervious concrete that is partially saturated should have "sufficient voids for the movement of water and thus demonstrate good freeze-thaw resistance." The key point here is that total saturation should be avoided for optimum freeze-thaw durability. What about clogging? The majority of pervious concrete pavements will function very well with little or no maintenance. However, there may be instances where sand, dirt, leaves and other debris may infiltrate the void structure of the pervious concrete and inhibit its permeability. In most cases, the clogging is limited to the first 1 to 11⁄2 in. of the pavement thickness. Routine cleaning can help avoid this situation and restore better than 90 percent of original permeability. A recent study by the University of Central Florida supports this claim. The research, conducted at the Stormwater Management Academy and funded by the Ready Mixed Concrete Research and Education Foundation, looked at eight pervious parking lots ranging in age from 6- to 20-years-old. These lots had seen little or no maintenance since their construction. The cleaning techniques investigated were pressure washing, vacuum sweeping and a combination of these two methods. Pressure washing dislodges the clogging particles, washing a portion offsite and flushing the remaining portion through the pavement surface. Vacuum sweeping dislodges the dirt and debris by means of the sweeping action and removes them via the vacuum. Results of the UCF study show that utilizing either pressure washing or vacuum sweeping can improve the infiltration rate of clogged pervious concrete by 90 percent. Cleaning with a combination of the two methods actually caused a 200 percent increase in infiltration rates over the benchmark infiltration rates of the clogged samples. However, the best maintenance practice appears to be prevention. Proper design and construction of pervious concrete should include consideration of the drainage of surrounding areas to prevent the flow of potentially clogging materials onto the pavement surface. Whenever possible, drainage of all unpaved areas should be away from the pervious concrete pavement. Additionally, landscaping materials, such as mulch, should not be stored on the pavement even temporarily. Your state's regulatory agency and pervious In 1972, the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) program was established under the authority of the Clean Water Act. This regulation requires communities and public entities that own and operate a municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4) to obtain an NPDES permit for stormwater discharges. As a part of the permitting process, the permit applicant must establish a best management practice (BMP) for stormwater management. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has approved several BMPs for stormwater management, and pervious concrete is among them. Though pervious concrete is not new, its use in stormwater management is a relatively new concept to the engineering community. As such, projects utilizing pervious concrete are undergoing special scrutiny. Most states include porous pavements, in general, as an accepted BMP but are reluctant to give blanket approval for all projects utilizing pervious concrete. Instead, they provide approval on a case-by-case basis, usually through special provisions to existing regulations. Tom Evans, promotion director for the Maryland Concrete Promotion Council, explains the process: "If you were going to build a road that crosses a stream, you can either build a bridge or place a culvert with backfill for an at-grade crossing. Either way, you must submit a completed design for approval. You can't just say, 'I'm going to put in a bridge.' The same applies for pervious concrete pavement. You can't just say, 'I'm using pervious concrete' and expect blanket approval. You need to submit a completed design with full details." To facilitate a smoother approval process, it helps to do your homework. The common concerns of regulatory agencies deal with pervious concrete's freezethaw durability, infiltration capabilities and pollutant removal efficacy. Research has been conducted on all of these issues, and the results are readily available. Dr. Heather J. Brown of Middle Tennessee State University and coordinator for the Concrete Industry Management Program has completed Pervious Concrete Research Compilation: Past, Present, and Future. Funded by the RMC Research and Education Foundation, the compilation serves as an index of texts, case studies and research projects for all aspects of pervious concrete including construction techniques, durability and maintenance, hydrological and environmental design, concrete mix design, specifications, test methods, and structural design and properties. The report is available online through the Foundation's website, www.rmc-foundation.org. Other supporting reports and documents are available through the NRMCA's website www.PerviousPavement.org. There are many resources for in-depth information on pervious concrete, but perhaps the best resource is your state or local ready mix concrete association. Contact them for more assistance on identifying existing local projects, assistance with the approval/permitting process, or to become a certified pervious concrete contractor.