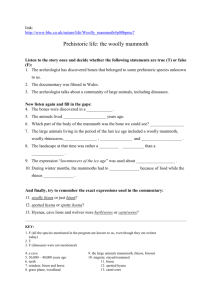

Burlington Hawk Eye, IA 09-25-07 Woolly weather

advertisement

Burlington Hawk Eye, IA 09-25-07 Woolly weather By KILEY MILLER kmiller@thehawkeye.com Seventy-five degrees. That's what the weather experts expect today. Seventyfive degrees and a chance of rain. Such joint-soothing heat makes it hard to believe that on this day 65 years ago it snowed in Burlington. And not just a dusting either. We're talking an honest-to-gosh whitewashing that prompted this newspaper to run a photo of a six-year-old boy tugging his sled. A headline above the picture read, "Well, it's only 91 days until Christmas." That, plus the traffic accidents that accompanied the storm, suggests folks here were surprised by Old Man Winter's premature appearance. Apparently, they hadn't been watching the woolly bears. That's right, woolly bears, nature's infallible forecasters, who in their black-brownblack bodies hold more information than any farmers' almanac about the coming season's snow, ice and cold. No fuzzy science here, no Doppler radars and sunspots. The truth is only an inch away -- the blacker the caterpillar, the worse the weather. Not so fast, says Donald Lewis, a bug guy at Iowa State University. Lewis ought to wear a T-shirt that says, "Entomologists have more fun," because he is one witty fan of the insect world. And no woolly bear is going to pull the wool over his eyes. "As for the belief that they can predict the weather," Lewis said last week, "that is simply not scientifically valid." When his listener laughed, he added, "I love to say scientifically valid. It sounds so much better than calling it hogwash." First, let's be clear. There are plenty of caterpillars out there, some red, some green, some all black, but we are only interested in the striped variety. Called woolly worms in the south, these two-toned titans of folklore are the larval form of the Isabella tiger moth. A medium-sized fellow with yellow-orange and cream-colored wings dappled by black spots, the Isabella is common from the top of Mexico to the bottom of Canada. Here in this neck of the woods, two batches of the woolly ones hatch each year, one in spring and the other in mid-summer. The early arrivals spend about eight weeks munching dandelions, clover and other green goodies before hiding in a cocoon for the caterpillar version of a mid-life identity crisis. They emerge from this forced rehab as moths, woolly no longer. Second-cycle bears aren't so lucky. Lacking time to turn into moths before the temperature drops, they must wait out the winter just as they are. This is why fall is the perfect time to spot woolly bears -- or to squish them under your car tires. "One of the great disappointments of my career," Lewis said, "is the fact that I haven't been able to come up with a clever answer to this question, 'Why did the woolly bear cross the road?' " (At this point, one of our reporters suggested, "To justify the entomologist's job.") Lewis might lack a clever answer, but he does have a scientific answer. Because woolly bears won't be protected by a cocoon, they have to search out rock crevices and other sheltered spots in which to hibernate. The woolly bears seen creeping suicidally across country pavement are out house hunting. In an interesting, if tangential, bit of trivia, woolly bears have a cousin in the arctic that lives up to 14 years, freezing solid in the winter and thawing each summer. Of course, people in the arctic don't need insect meteorologists. They know its going to be cold. But here in the lower latitudes, the mercurial weather demands some means of prognostication. While Lewis may bristle at the woolly bear, others are far less skeptical. Next month in Banner Elk, N.C., up to 20,000 people will turn out for the annual Woolly Worm Festival. The signature event is the woolly worm "waces," in which whiskery athletes sprint up suspended strings in pursuit of fame and more than $1,000 in prize money for their trainers. Last year's winner was a speedy little pipe cleaner named Jerry Garcia. In addition to the prize money, he had the honor of being used in Banner Elk's official winter weather forecast. Selecting a specimen in this way eliminates one of the chief inconsistencies of woolly bear watching; namely, that they are not all created equal. Two found side-by-side might wear totally different coats. In fact, this article wriggled to life when a young man in Henry County reported seeing almost totally black "bears" on the back roads of Henry County. That would seem to ensure a severe winter, except ... "I found one the other day that was blond," said Jack Thomas, a retiree and parttime farmer from rural Lowell. "What do you make of that?" Polar bear, perhaps? Even if the woolly bear population were whittled to one, there would still be an argument over how to interpret his body language. "It all depends on the farmer you talk to," said Rick Van Winkle, a Mount Pleasant man who grew up in rural Lee County playing with "woolly boogers" instead of woolly bears. "Are they going from west to east, or east to west. Are they more black or more brown." The most common method seems to be one in use at the Woolly Worm Festival in North Carolina. A woolly bear's body is broken into 13 segments. According to the festival system, these represent the 13 weeks of winter. Each black ring indicates a week of frigid, windy misery, while each brown ring suggests happier skies. That means a caterpillar like Jerry Garcia, with his long brown body and only a touch of black around his head, foretells a biting December followed by gentler weather in January, February and March. In 23 years of the festival, the woolly oracles have proven accurate 57 percent of the time. Those numbers may be somewhat suspect, though. That's why we owe a debt of gratitude to C.H. Curran. Back in 1948, Curran, then the curator of insects at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, got the happy-go-lucky idea to judge the predictions of woolly bears upstate at Bear Mountain State Park. So he and some pals collected 50 caterpillars off the mountain, counted the brown rings and calculated the average. This not-so-intense effort continued over the next eight Octobers, with the woolly bears consistently forecasting mild winters that regularly followed. It's obvious Curran didn't take the enterprise too seriously. His band of researchers called themselves The Original Society of the Friends of the Woolly Bear and included "Planet of the Apes" actress Kim Hunter. The woolly bear counts ended in 1958 and did not begin again until three decades later when Jack Focht took over as museum director at Bear Mountain State Park. Focht is in his 70s now, but he still gets to chuckling when he reminisces about the good old days of caterpillar snatching with his friend and "folklore consultant," Clarence Conkling. "We used to always say we were 80 percent accurate," he said last week from his home in New York. "We could get away with it because nobody could remember what we'd predicted the summer before." On the rare occasions they did remember, though, things could get pretty hairy. "Some years people got really into it," Focht said. "We got pelted with snowballs and had snow stuffed down the shirt when we were wrong." Even with those hiccups, Focht thinks it is an injustice that the world's most trusted animal meteorologist remains the groundhog, Punxsutawney Phil. "We can make a prediction now about the whole winter," he said. "He has to wait until February." Focht stopped collecting woolly bears when he retired, but he couldn't help eyeballing one around his place the other day. There was a lot of brown. That doesn't quite match up with "The Old Farmer's 2008 Almanac," which calls for above average precipitation this winter in upstate New York. Then again, the almanac also claims temperatures in Iowa and Illinois will be two degrees above normal with below average snowfall, and that simply can't be true -- not with all those dark, dark woolly bears creeping around. Unless, of course, the wive's tale is wrong. According to Lewis at Iowa State, researchers have actually figured out that woolly bears have more black on them when they are young or when the fall months are unusually wet. In other words, they do explain the weather -- it's just weather that has passed. Thankfully, there are plenty of other old saws out there. Van Winkle has heard any number over the years: If there was fruit in the orchard last year but not this year, expect plenty of snow and cold; no nuts on the trees means the squirrels are hoarding. Which does he rely on? "They always told me it was going to be a bad winter," he said, "if the Indians were putting up a lot of wood."