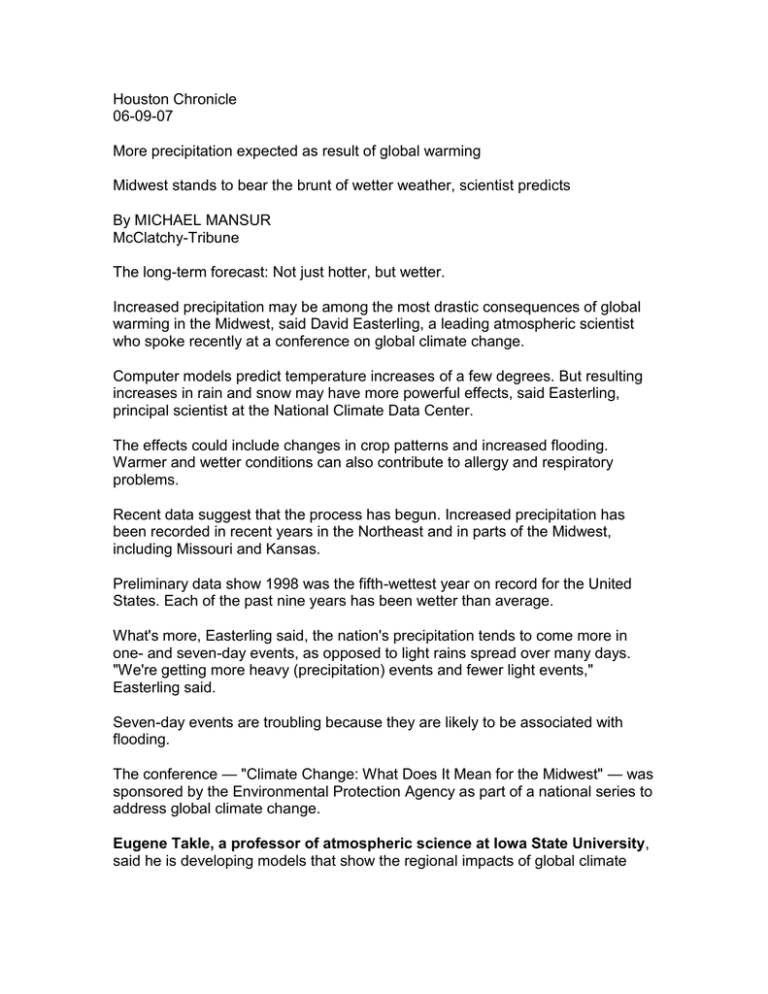

Houston Chronicle 06-09-07 More precipitation expected as result of global warming

advertisement

Houston Chronicle 06-09-07 More precipitation expected as result of global warming Midwest stands to bear the brunt of wetter weather, scientist predicts By MICHAEL MANSUR McClatchy-Tribune The long-term forecast: Not just hotter, but wetter. Increased precipitation may be among the most drastic consequences of global warming in the Midwest, said David Easterling, a leading atmospheric scientist who spoke recently at a conference on global climate change. Computer models predict temperature increases of a few degrees. But resulting increases in rain and snow may have more powerful effects, said Easterling, principal scientist at the National Climate Data Center. The effects could include changes in crop patterns and increased flooding. Warmer and wetter conditions can also contribute to allergy and respiratory problems. Recent data suggest that the process has begun. Increased precipitation has been recorded in recent years in the Northeast and in parts of the Midwest, including Missouri and Kansas. Preliminary data show 1998 was the fifth-wettest year on record for the United States. Each of the past nine years has been wetter than average. What's more, Easterling said, the nation's precipitation tends to come more in one- and seven-day events, as opposed to light rains spread over many days. "We're getting more heavy (precipitation) events and fewer light events," Easterling said. Seven-day events are troubling because they are likely to be associated with flooding. The conference — "Climate Change: What Does It Mean for the Midwest" — was sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency as part of a national series to address global climate change. Eugene Takle, a professor of atmospheric science at Iowa State University, said he is developing models that show the regional impacts of global climate change. The models must be refined over the years before scientists will have a clear picture of future impacts. Takle said the argument of persons who dismiss global climate change — that satellite temperature data contradict surface temperature data — has been largely dismissed by scientists. "That foundation is slowly crumbling," he said. Since the Industrial Revolution, increased amounts of "greenhouse" gases, including carbon dioxide, have been emitted into the atmosphere. These are known to increase warming, but the effect of the buildup won't be felt for decades. Carbon dioxide has a long life: One-third of what is released today will be around in 200 years. "One of the legacies we're leaving to future generations is the amount of carbon we're putting into the atmosphere today," Takle said. The conference also addressed some economic impacts of global climate change. Chris Horner works for the Cooler Heads Coalition, an industry group concerned about the impact on the U.S. economy of efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions. He said global climate change is too much a theory to take drastic and costly actions such as mandatory limits on industrial emissions, as prescribed in the Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty that calls for the United States to reduce its emissions of greenhouse gases to 7 percent below the levels emitted in 1990, beginning in 2008. Horner said some computer models of the economic impact of meeting those targets show the loss of 2.4 million jobs and hundreds of billions of dollars. Joe Aldy, senior adviser for the White House's Council of Economic Advisers, said the models Horner cited are flawed. The White House, under its most optimistic scenario, predicts as little as $12 billion in impacts. "It's not the 3 to 4 percent of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) that some people claim," Aldy said. "It's more like a tenth of a percent." That translates to about $110 per household each year in increased utility bills, a 5-cent-per-gallon increase in gas prices and less than half a penny more per kilowatt hour of electricity. David Gardiner, the Environmental Protection Agency's assistant administrator for policy, called the Kyoto Protocol "an affordable insurance policy." The administration thinks the effects of global climate change are likely to be "more bad than good," he said.