Sioux Falls Argus Leader, SD 03-04-07 Can $400M change a city?

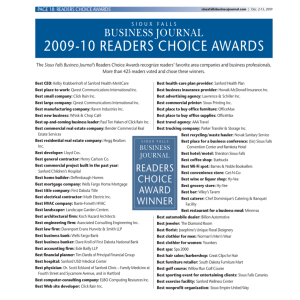

advertisement

Sioux Falls Argus Leader, SD 03-04-07 Can $400M change a city? Sanford gift could reshape Sioux Falls' image, fortunes By Jon Walker jwalker@argusleader.com Sioux Falls is full of ideas. Some are found in the words of people with power and money. The rest belong to lesser- known residents who wonder today what's ahead for their community. They say the $400 million banker T. Denny Sanford gave the former Sioux Valley Hospitals and Health system - now Sanford Health - has changed Sioux Falls or even vaulted it to a higher status among American cities. But that idea itself is a hard sell. To many, the city actually is a town locked in adolescence, a place for teenagers to grow up and leave. "There's a life out there," said Nicole Wermers, 18, who plans to make her exit soon after graduating from Roosevelt High School. She hopes to become a doctor. To them, the power of Sanford's gift is not that it changes the everyday thinking on the streets or turns a happy burg into a mecca of culture and opportunity. Instead, the donation finds its place on a timeline that shows Sioux Falls with its share of faults but also growing in prosperity and population. "I don't see it as starting a revolution. I think it's a piece of a larger picture," said Rich Bowman, religion professor at Augustana College. The magnitude of the donation is difficult to conceive. A sum of $400 million is more than 5 percent of the $7.6 billion total of assessed value on property in Sioux Falls. It's spawned some chest-thumping that cuts against the grain for residents who value modesty. One billboard trumpets Sanford's donation as though Isaiah the prophet had dropped in to declare: "A gift has been given." But if Sanford had put $250,000 into a brown bag and secretly dropped such a bag once a day, every day, at the front desk in the Sioux Valley lobby, it would have taken 41/4 years to complete his donation. It's a lot of money. More difficult to conceive is its effect on the character of the community. Sioux Falls is a town where an innocent man, Thomas Egan, was hanged in 1882. It once was a divorce colony and a nest for the Ku Klux Klan. Today, graffiti is front-page news and business is humming at 146 gambling establishments. Sioux Falls also is among the most generous spots on the map and in 1992 scored Money magazine's mark as the best city in America. It's become a racial melting pot where the economy, known once for its smokestacks and aroma on cloudy days, is a white-collar haven for banking and medicine. The young might leave, but the net gain still is 10 people a day. The population, 148,000, has doubled in 30 years. Pamela Riney-Kehrberg, professor at Iowa State University, said, "Midwestern cities are having a hard time." As such, Sioux Falls bucks a trend, she said. Climate's a problem. Two interstate highways meeting here is a benefit. A gift such as Sanford's should be seen for what it is, she said. "If you set out to say we have the resources and want to be the regional medical center for the Northern Plains, that's entirely possible," said Riney-Kehrberg, head of agricultural history and rural studies at Iowa State. "It all depends on good planning and hard work." Most ambitious pursuits have met mixed results But it's difficult, she said, for one gift to change a community mind-set about getting over the hump to address problems or set ambitious priorities. Sioux Falls has tasted triumph and defeat in chasing bold ideas. The Washington Pavilion rescued an old high school and became a regional landmark. Falls Park is clean again. The Lewis & Clark pipeline stands to clear up doubts about water supply. On the other hand, a plan to punch a road through the country clubs to connect east and west fizzled. So did an effort to bring in a pro football summer camp. When residents were asked 15 months ago to build a $32 million rec center, twothirds said "no." Sanford's plan for a dome on an expanded hospital campus recalls that others for years have thought a dome would make sense at Howard Wood Field. Mike McCurry, extension rural sociologist at South Dakota State University, said a good deal is at stake in how Sioux Falls sees itself. "You've moved past a city. It's a metropolitan area," he said. Sanford's gift could accelerate the transition, just as availability of health care grows as an issue in defining the state's quality of life. "We're going to wind up with an urban area along the east edge of South Dakota, a bit around the state capital and a touch in the Black Hills," McCurry said. "We wind up with so much more remote area, making it much harder to live in rural South Dakota." Keeping that gap from making life worse could be one bold undertaking for the city. Yet visions of greatness need careful selection, Riney-Kehrberg said. There's a place for off-the-chart thinking, but within a framework of a city's strengths that depend more on day-to-day living than a flair for brainstorming. Sioux Falls, for example, could become a regional power in medicine, she said, but it probably never will host the Olympics. "You have to be able to see yourself," she said. "It's sad to say, but a lot of Midwestern places need to fashion themselves around modest aspirations. That's simply demographic reality. But that doesn't mean you can't be the best medium-sized city in the Midwest." N.Y. transplant sees true city emerging Richard Kamolvathin, a native of Thailand, grew up in Queens and was a bond trader on Wall Street. He's now a financial representative for Northwestern Mutual. He calls Sioux Falls his freedom and his breath of fresh air, but isn't sure he'd call Sioux Falls a city. "Is it the economy?" he asked. "Is it culture? Is it people? Does it mean skyscrapers? It's already to the point where we barely know our neighbors. If that constitutes a city, we're almost there." But not quite. He said he can't drive his silver Cadillac down 41st Street without waving to people he knows. People call him by name when he shops. He rode a bus, train and ferry to work in New York. Now, it's a five-minute drive home to eat lunch with his son. For him, Sioux Falls is a courteous community with an edge. "It's a tough town," he said. "It's a cowboy town. It's not city tough. It's a lot of grit. Be straightforward. Be blunt." Wermers, the Roosevelt student, doesn't see leaving as a rap on her hometown. "A lot of people come back to South Dakota and Sioux Falls, but a lot of people have to explore what's out there," she said. Some intent to leave, explore no matter what Bowman, 58, did just that. He graduated from Lincoln High School in 1967 and earned a Ph.D. at Union Theological Seminary in Virginia before returning in 1981 to take a job at Augustana. He and his family live in the same house he grew up in on 21st Street east of McKennan Park. Another was Bryan Bjerke, 56, a television reporter who moved to New York for two years and then returned to be closer to his family. He's from a dairy farm near Volga. Bjerke, today a public relations strategist for Paulsen Marketing Communications, thinks the Sanford announcement, along with growth plans at the Avera McKennan health system, "quickly changed the face of Sioux Falls." Residents are skeptical about how such news might affect them, but they also see a broader imprint, he said. "It gives a certain sense of optimism to people that life can be better." Optimism can lead to bold thinking, and that can be contagious. But that's an undue burden to tie to the Sanford gift, Bowman said. He wonders whether the donation will polarize the economy, with an influx of well-paid medical professionals leading to a lesser role for the middle class. He said that right now the city is striking for its personal nature and openness. He lives within a block of his state legislator and a former city councilor. "You see the mayor at Canaries games," Bowman said. Ashley Matelski, 18, said it will take more than a gift like Sanford's to change the outlook for Sioux Falls. "We're a town, not big enough to be a city," said Matelski, who counts herself among those who "definitely would leave." Robert Frazier, 19, a marketing student at the University Center, said he would classify Sioux Falls as "right now a town, but in a couple years a city." The Sanford gift may push that transition along and might even change the way people think about themselves. But he too plans to leave "to find out if we're right, that there's more out there." South Dakota law once classified communities as cities, towns and villages, but today defines them as first-, second- and third-class municipalities. That leaves talk of "city or town" a matter of context. If city sounds sophisticated and progressive, town sounds warm and personal. "It's maybe the difference between house and home," said Karly Ward, 21, an art and English student at the University of Sioux Falls. Sioux Falls would need a makeover to become a complete city in Ward's mind. She's a painter, a photographer and vegetarian who serves steamers and latte at the all-night Sankofa coffee shop on 41st Street. That such a shop is a novelty only reinforces her point. It's not a slam, she said, just an observation. She'll be interested to see whether Sioux Falls, with the Sanford gift, does become more cosmopolitan. "I plan to leave and go to grad school," she said. "It's hard to say if I'd come back because I don't know what would be here." Reach reporter Jon Walker at 331-2206 or 800-530-6397.