USA Today 11-24-06 Experts see pros and cons in teens' online socializing

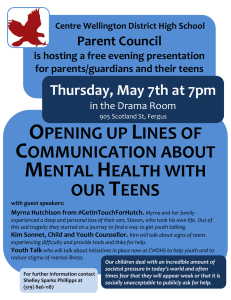

advertisement

USA Today 11-24-06 Experts see pros and cons in teens' online socializing By JANET KORNBLUM USA Today Brittnie Sarnes has 5,000 MySpace friends. Actually, make that 5,036. At last count, anyhow. About 10 people a day ask to "friend" her. Usually she says yes. She knows they're total strangers, but it doesn't matter. Each time she's asked, it feels "kinda cool — like 'Oh, this person thinks I'm cool enough to befriend me,'" says Brittnie, 17, of Columbus, Ohio. From there, anything can happen. The person might "comment" on her page. She might send her e-mail or an instant message, and they could start a conversation. They might even become real-life friends. But probably, she'll just sit on Brittnie's list, joining the 90 percent of her friends with whom she has virtually no contact. Call it a hobby. Call it an obsession. Call it the new way of socializing in the networked world. Call it "friending," the way millions of teens and young adults obsessed with social networking sites such as MySpace and Facebook are making connections. Friendship always has been a tricky game, especially for teens. But in the past it was played out in school hallways, on playgrounds and in late-night phone calls. These days it is happening in full color on the computer screen — often in front of the world. And it can be confusing, especially for teens trying to fit in. How many friends should one have? What kind of friends should they be? Are online friends "real"? Does it help boost self-esteem, or might it be harmful? There are no rules. "They're evolving," says Peter Post of the Emily Post Institute, the etiquette and manners clearinghouse. For Valerie Smithers, 17, "it's kind of like entertainment." But she adds, "My family members and all my friends make fun of me. I'm so, like, into it." But Amanda Peters, 17, worries that friending teaches teens bad social skills. "All these friendships aren't real," says Amanda, who recently wrote a story for a teen literary journal about how friending is getting out of control. "If anything happens where you get annoyed with them, you can just delete them from your list and never have to worry about them again. "If I get mad at my friend that I go to school with, I can't just erase her from my life. She's still a person. She still exists. I'm going to have to interact with her." But friends lists are filled with all sorts of friends — from best friends to virtual strangers. "The idea of actually meeting all your friends on your MySpace page is just strange," says Danah Boyd, a social media researcher for Yahoo. "You wouldn't do that." Michael Bugeja, director of the Greenlee School of Journalism and Communication at Iowa State University and author of "Interpersonal Divide: The Search for Community in a Technological Age," says real friends can never be replaced by online ones. "Friending really appeals to the ego, where friendships appeal to the conscience," he says. When people friend others online, "they're making social contacts." But those friends could develop into "more substantive" relationships, he adds. For some, friending is not just a pastime, it's also an indication of social success or failure, says Susan Lipkins, an adolescent psychologist in Port Washington, N.Y. "If you go to college and you don't have a full bunch of people on your MySpace or Facebook, then it's implying that there's something wrong with you," Lipkins says. "Listing your buddies and your friends is a way of establishing yourself, of feeling connected and feeling like you're accepted." And for younger teens, especially, "friending is a way of finding status and is the definition of who you are online," says Parry Aftab, an expert on teen safety and the Internet. "You're judged by your friends list." Just in case you were wondering: Size matters. For some, such as Brittnie, status comes with having extremely long lists of friends, although most MySpace and Facebook users have a few hundred. "Some people used to collect pet rocks or trinkets or stamps," says Amanda Lenhart, a senior researcher and specialist in teens and technology at the Pew Internet & American Life Project. "And some people collect friends — to see how many people you can put onto your network. Some of it is seen as a proxy for popularity." Lists can be faked Competition for friends can be so fierce that ad-supported Web sites are cropping up. They plug you into a system where you can start automatically generating friends — or where you can generate fake friends — to make lists look fat. Some say overly long lists can smack of desperation. When Georgia Bobley, 18, a student at George Washington University in Washington, sees a page with more than 500 friends, she thinks "it's a little creepy." But having too few friends might mean you're not very popular. "When I go onto somebody's Facebook profile, and they have four friends, I'm like, 'Oh, my God. What? They only have four friends?'" She has 329. Valerie, who has 1,327 friends, says she will sometimes ignore list length for the right reasons. If she encounters someone with "only 12 or 20 friends, but they seem like a cool person, I'll start a conversation with them … They could've just started their site, too." Mostly, for Brittnie and a lot of others, friending is a kind of game. For others, though, especially younger teens, it's not a game. "There are lots of kids who go there looking for friends because they don't have them elsewhere," Aftab says. "And they'll find different ways of getting them. The standards may not be so high." At its root, competing for friends and fighting for status is hardly new behavior, Aftab says. Kids have always judged each other by the friends they keep. The Top 8 issue, for example, constantly causes teen angst, says Amanda Peters. That's the top eight friends displayed by default on a MySpace page. The rule is, you put your most important friends on your Top 8. "Some people get really (obsessed) about it. They're like, 'I'm on your Top 8, but why am I the eighth person? Like how come I'm not No. 2?'", she says. Those kinds of feelings are natural, Lenhart says. The online world "is a proxy for our off-line experience. It's not surprising that we get hurt when you see things that in the off-line world would be pretty hurtful. When you're rejected, it's being rejected." Friending is a work in progress, says Paul Saffo, a Silicon Valley futurist and technology consultant. "It's a good social experiment. Every generation finds its excuse for people to meet people. This is just this generation's thing. It will die back a little bit, and they will keep the part that works."