Bismarck Farm & Ranch Guide 03/02/06 Soybean aphids continue their march northward

advertisement

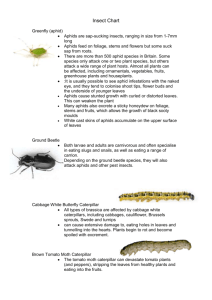

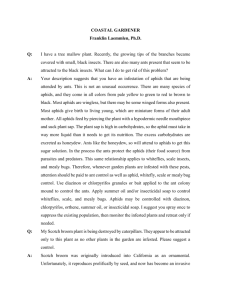

Bismarck Farm & Ranch Guide 03/02/06 Soybean aphids continue their march northward By DONNA FARRIS, For Farm & Ranch Guide In their short five-year history in South Dakota, Minnesota and Iowa, soybean aphids have spread to virtually every soybean production area. The pattern seems to be a greater outbreak in odd-numbered years with lesser problems in even-numbered years. But experts warn growers against letting their guard down based on that fact for 2006. “It would be tempting to put some reliance on the every other year phenomenon, but I wouldn't count on it,” said Ken Ostlie, University of Minnesota Extension entomologist. “I wouldn't count aphids out because every year is a problem somewhere.” Ostlie said aphids affect soybean fields throughout Minnesota. Aphids have been found in every county in Iowa, said Marlin Rice, Iowa State University Extension entomologist, with northern counties tending to have larger infestations than southern counties. “This insect has gone through biannual cycles of highs and lows, but it's only been here five full years. So I think it's premature to put much stock in the cycles that we1re seeing,” Rice said. In South Dakota, aphids have been found in most counties in the eastern half of the state. “We're finding them now in the most remote soybean production areas in South Dakota,” said Craig Rosenberg, Minnehaha County, S.D., Extension agronomy educator. For the first time in 2005, soybean fields in northeast South Dakota were treated and spraying was widespread throughout counties where soybeans are grown. “It looks like a pest that's not going to go away,” Rosenberg said. The soybean aphid has continued its spread northward and that's cause for concern, said Mike Catangui, South Dakota State University Extension entomologist. “I think the aphid will be important again. Since 2001, every year we have had to spray,” he said. Soybean aphids are an introduced pest from Asia and have been in the United States for at least six to seven years, Ostlie said. The aphid was first introduced in the vicinity of Chicago or Milwaukee. “It has spread literally across most of the soybean growing areas of the United States with the exception of the South,” Ostlie said. Aphids colonize soybeans anytime from when the unifoliate leaves appear and may remain in the field until leaf drop. The aphids insert their stylets into the plant's “plumbing,” where they suck out photosynthetic products, according to Ostlie. “They are removing products that the plant would be using for growth and yields and so in a sense, they are robbing the plant of some of that capacity,” he said. Populations in the summer can double on the plant in as little as two days. Aphids seen on the soybean plant are almost entirely female. “They reproduce essentially by cloning. They don't require any mating and produce live young during the summer. Populations can blow up very quickly,” Ostlie said. Also, the bugs are capable of long-distance dispersal. “They are at the mercy of the wind and are capable of moving fairly significant distances,” Ostlie said. When the insects are overcrowded on the plant they will form wings, Catangui said. “After they have developed wings on the soybean plants they are pretty much out of control,” Catangui said. “We have a very long window when aphids can colonize a field and infestations can build up,” Ostlie said. If aphids are abundant early enough, their damage will affect the soybean plant and stunt canopy growth. “As the populations carry over into the reproductive stage of the plant, you'll see consequences in yield, in terms of reduced pod number, reduced number of seeds and reduction of seed weight,” Ostlie said. Aphids have a fairly complex life cycle. They over-winter on buckthorn, a shrub introduced from both Europe and China. On the buckthorn, aphids reproduce sexually. Females mate with males and produce eggs. Originally, buckthorn was grown in windbreaks in the Dakotas. The European buckthorn is spread readily by fruit-eating birds. “It now occupies a major part of most farm groves as well as river forests,” Ostlie said. Experts say scouting for aphids is critical. Rosenberg recommends scouting from early July to early August. “You've got a six- to eight-week scouting window when aphids could be a threat,” Ostlie said. If aphids are present, they can multiply from 100 aphids per plant to nearly 800 in a week to 10 days. “It's not a problem you can see from the road,” until the problem is too advanced to do anything about it, Ostlie said. “Growers need to be out there scouting before things get out of hand.” Minnesota and Iowa Extension experts both recommend a threshold of 250 aphids per plant before spraying. In South Dakota, Catangui recommends lower thresholds based on the economics of the cost of spraying versus the price of soybeans per bushel and potential yield. In areas which typically see higher yields, growers can afford to spray at lower thresholds, he said. For example, it can pay to spray when only eight aphids are found on a plant at full bloom (the R2 stage), if soybeans are bringing $6 per bushel. “The economic threshold is the percent of your yield that will pay for your spray,” Catangui said. More detailed information can be found at the Web site, http://.plantsci.sdstate.edu/ent “The aphids are tiny and it's easy to underestimate numbers,” Ostlie said. They start out clumped near the top of the plant around newly emerging leaves. As the pods develop and fill, aphids are located throughout the plant with numbers peaking in the middle of the plant. Scouting recommendations are available on the University of Minnesota Extension Web site, http://www.soybeans.umn.edu Rosenberg said farmers should look for aphids on growing points. “You want to go to the newest, freshest growth,” he said. “Spread the leaves apart, look on the upper stem and look on the underside of the leaves,” Rice said. Rice said growers ought to find the threshold number of aphids on a dozen or 15 plants in a field before making the decision to spray. “One plant by itself is not anything to get excited about. If a farmer is going to spend money to control a pest he should make sure that insect is present across the field on a number of plants,” Rice said. The best time to spray is typically late July and early August, Ostlie said. Before that point, aphid populations aren't typically high enough for maximum effectiveness. Catangui said SDSU trials compared different treatments for aphids and found spraying at the right time to be more effective than seed treatments by up to 7 bushels per acre. Catangui recommends spraying when the plant is at the full bloom stage, or R2. R5, when the seed is about one-eighth inch long in the pod, is the last stage when treatment will be effective, he said. “If you want to maximize your yield you have to deal with this insect,” Catangui said. Last year, in fields where growers sprayed, they saw 4 to 17 bushel yield increases, Ostlie said. “It's well worth a grower/s time to keep track of what's happening with aphids,” he said. In test strips with high aphid populations and no treatment, researchers have seen losses of up to 60 percent, Ostlie said. “They will not totally eliminate fields, but it can be economically devastating. When you consider the cost of application is running less than 2 bushels per acre, it's extremely worthwhile to do that scouting,” Ostlie said.