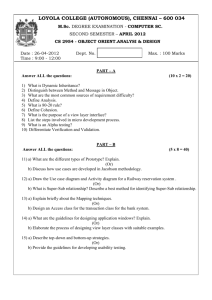

ESIGN ACTS

advertisement