( AMERICA AND ASIA IN A CHANGING WORLD HEARING COMMITTEE ON

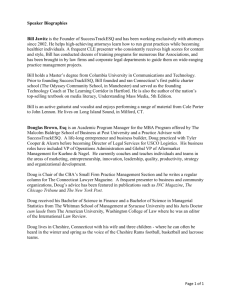

advertisement