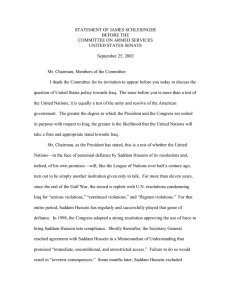

( WHAT’S NEXT IN THE WAR ON TERRORISM? HEARING

advertisement