Report on Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan

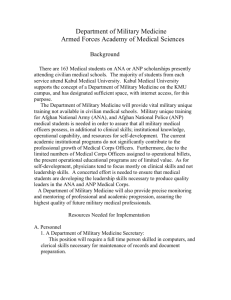

advertisement