The Hubble Constant Neal Jackson

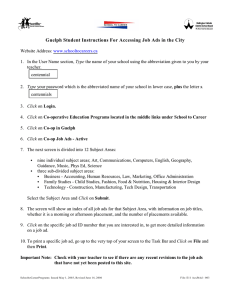

advertisement