Pronunciation in the Language Teaching Curriculum Iowa State University

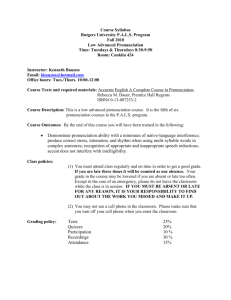

advertisement