Introduction Let me begin with a trick question: Do you know... the most rudimentary familiarity with sociology has run across this...

advertisement

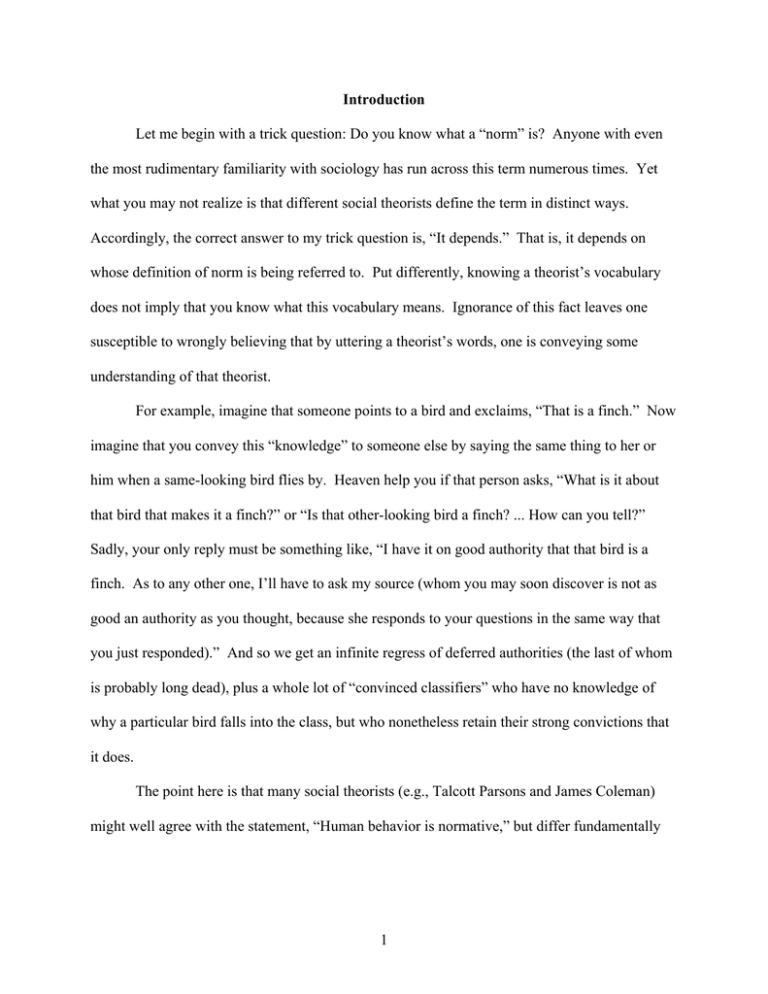

Introduction Let me begin with a trick question: Do you know what a “norm” is? Anyone with even the most rudimentary familiarity with sociology has run across this term numerous times. Yet what you may not realize is that different social theorists define the term in distinct ways. Accordingly, the correct answer to my trick question is, “It depends.” That is, it depends on whose definition of norm is being referred to. Put differently, knowing a theorist’s vocabulary does not imply that you know what this vocabulary means. Ignorance of this fact leaves one susceptible to wrongly believing that by uttering a theorist’s words, one is conveying some understanding of that theorist. For example, imagine that someone points to a bird and exclaims, “That is a finch.” Now imagine that you convey this “knowledge” to someone else by saying the same thing to her or him when a same-looking bird flies by. Heaven help you if that person asks, “What is it about that bird that makes it a finch?” or “Is that other-looking bird a finch? ... How can you tell?” Sadly, your only reply must be something like, “I have it on good authority that that bird is a finch. As to any other one, I’ll have to ask my source (whom you may soon discover is not as good an authority as you thought, because she responds to your questions in the same way that you just responded).” And so we get an infinite regress of deferred authorities (the last of whom is probably long dead), plus a whole lot of “convinced classifiers” who have no knowledge of why a particular bird falls into the class, but who nonetheless retain their strong convictions that it does. The point here is that many social theorists (e.g., Talcott Parsons and James Coleman) might well agree with the statement, “Human behavior is normative,” but differ fundamentally 1 on what this sentence means. 1 Theoretical statements are thus inextricably linked to the theorist being associated with them. Now note the almost comical dilemma to which this conclusion leads us: What about statements that compare theorists? If it is only legitimate to speak of a theorist in terms of her or his own technical vocabulary, does this imply that there is no vocabulary for distinguishing among theorists’ ideas? The usual response to these questions is to create a list. Since each theorist’s perspective is simply different from every other theorist’s perspective, our list is one of theorists’ names, followed by –ism or –ian (Marxism, Weberian thought, etc.). However, little is gained from such a radical relativism in which theoretical perspectives are as numerous as the surnames of social theorists at any point in history. So let us temper our relativism by collapsing under broader headings, those theorists who choose to identify themselves with a common label (constructionism, dramaturgy, etc.). Yet even now our original dilemma remains despite our having shortened the list of theoretical perspectives in this way. Although either list of labels provides us with a vocabulary for referencing theories, we still lack a grammar for distinguishing among them in a consistent way. Consequently, we still lack a language for discussing theories. I submit that a grammar for distinguishing among the entities in our list (namely, social theories) must be based on a definition of “social theory.” So what is a theory? A theory (my 1 Although one may be hard-pressed to find commonality in theorists’ usages of a concept like “norm,” such terms have considerable value in comparative theoretical work as “pivotal concepts” for contrasting perspectives. For example, Parsons (1951, pp. 11-13) argued that norms place self-imposed limits on how far actors’ goal pursuits may go before they threaten the survival of the institution within which they are enacted. In contrast, Coleman’s (1990, p. 243) position is that normative behaviors result only because others believe themselves to have a right to enforce conformity. Thus although norms are “socially acceptable behaviors” for both, there are fundamental differences—indeed inter-theoretical inconsistencies—in their explanations of “who” accepts “whose” behaviors. 2 definition) is a language for explaining sensory experiences; a social theory is a language for explaining human behavior. So what is a language? A language consists of a vocabulary plus a grammar of rules for the correct usage of this vocabulary. Mastering theorists thus involves not only memorizing their respective vocabularies, but also gaining fluency in each of these vocabularies’ correct usage. In many respects, studying a set of social theories is like studying the same number of foreign languages. Yet the former is much more difficult, given that social theorists are notorious for not setting out their grammars in straight-forward, axiomatic ways. Instead, they tend in their writing simply to apply their grammars and to leave their readers the task of inferring underlying grammars from their usage. The student’s skill is more sophisticated than that of the child who learns to mimic its parents’ use of, say, Norwegian, however. Reading social theory calls for making explicit (or deconstructing) the grammar underlying each theoretical perspective at hand. Of course, familiarity with a spectrum of theories is a laudable objective for readers. But the more important outcome—the one that allows this spectrum to expand—is the development of the deconstruction skill itself. It is my hope that this objective is not only your motivation in studying social theories, but also the outcome this course of study affords you. Returning to my above definition of theory, one notes that a link is presumed between theoretical languages and sensory experiences. Ferdinand de Saussure ([1915] 1983) is credited for having first emphasized the distinction between language (langue) and articulation (parole), where the former establishes a static set of expectations regarding the latter. Yet for de Saussure the experiential world consists of static units to which linguistic signs simply correspond. This assumption of an intact world of referents has perhaps been most sharply criticized by Jacques 3 Derrida (e.g., [1967] 1976), who argued that concepts’ links to sensory experiences (or ‘traces’) are just as tentative as their links to language. Derrida proposed “the hinge” as a metaphor for a concept’s simultaneous relation to both language (through articulation) and sensation (through différance). Whereas articulations vary in the degree to which they accord with expected language usage, immediate différance varies in the degree to which traces accord with expected (i.e., a history of past) sensory experiences. Thus there is a “dual life” in people’s expectations regarding the concepts they apply to their existence—grammatical expectations potentially at odds with a present articulation and sensory expectations potentially at odds with immediate différance. Figure 1 provides a graphic depiction of the concept’s dual life as a hinge. At one end of the hinge is a theory’s static grammar—its rules for the proper articulation of this among other concepts in its vocabulary (i.e., for its proper conceptualization). At the other end of the hinge are immediate experiences that may or may not jibe with one’s expected sensations regarding these concepts (i.e., one’s conceptions). Although not acknowledged in Derrida’s writings, this metaphor has long been grasped by the scientific community in the sense that scientific theories are simultaneously logically consistent and open to empirical verification. Each theory’s grammar affords logically consistent rules for articulating the concepts in its vocabulary. Yet these concepts must each have an operational definition (i.e., measurement criteria) before verification can proceed. That is, not only must scientists’ hypotheses be expected (i.e., logically derived) in accordance with a theory, sensory expectations regarding the concepts in these hypotheses must also be agreed upon beforehand. 4 Grammar Conceptualization/ Conception Sensory Experience, or “trace” Figure 1. Derrida’s “hinge” depicts concepts’ dual nature as conceptualizations articulated according to a grammar and conceptions having différance with sensory experiences (from Roberts [2008, p. 7]). Complexity is added to scientific endeavor when the subject matter of inquiry shifts to creatures—namely, humans—with conceptions of each other that likewise hinge between language and experience (i.e., when we restrict our attention to social theories). In such cases, scientists must specify the language that their subjects use when referring to each other’s motivations. Accordingly, social theories are languages about people’s languages regarding each other. (And, yes, my efforts here are to develop a language regarding these languages about languages.) So how many of these languages-of-motivation are there? My answer to this question is based partly on the nature of the hinge itself, and partly on the fact that every language-of-motivation must incorporate a concept of “person.” First, although concepts’ dual life can be depicted graphically as a hinge, these lives can only be discursively addressed one at a time. Consider the challenge one faces in discarding an old trashcan. Despite one’s tenacity, it is repeatedly left at the curb. Trash handlers’ expectations for a 5 trashcan are that it indicates (or signifies) trash. As such, its existential status is “Is Not”, making it transparent to the handler. Likewise, linguistic competence is defined precisely in terms of the transparency of one’s speech and writing. Speakers who are unable to overcome a strong accent or severe lisp may never achieve linguistic competence in the “eyes” of their audience. The lisper’s words go unnoticed (i.e., they are “not”) until they fail to direct others’ attention elsewhere but call attention to themselves. Similarly, for the trash handlers the old trashcan’s status as a sign for trash remains “Is Not” until it fails as a signifier of trash, presumably because it is itself so trashy that it can no longer signify trash as they expect. (Roberts 2008, p. 29) In brief, articulation (e.g., within a language of trash removal) is other-referential, whereas différance is self-referential. During discourse the hinge’s concept is either a conceptualization that directs one’s audience’s attention elsewhere (e.g., from a trashcan to its contents), or a conception that calls attention to itself (e.g., as sufficiently trashy to “be” rather than to signify trash). Communication is impossible unless a consensus exists on whether one’s utterances are conceptualizations or conceptions. One cannot communicate both simultaneously. Conceptions and conceptualizations elicit distinct types of knowledge. Operational knowledge is required for a conception to become noticeable, whereas relational knowledge is made manifest in conceptualizations. 2 Most people whose native language is not English have distinct words associated with operational versus relational knowledge. Operational knowledge is referred to by the French as savoir, by Germans as Wissen, by Arabs as Al-Elm, and by 2 Merton (1972, p. 41), James ([1909] 1955, p. 209f), Grote (1865, p. 60), and numerous epistemologists (e.g., Hamlyn 1970, p. 104f; Woozley 1969, p. 24) have written on these two types of knowledge. The novelty here is in how the distinction is tied to the just-discussed dual nature of the concept. (Also see Roberts [2008, pp. 8-12].) 6 Chinese as Zhi-Dao. Their corresponding words for relational knowledge are connaissance, Kenntnis, Al-Ma’rifa, and Ren-Shi. For example, let’s assume that “I know a woman whose name I know no longer.” Not knowing the name leaves me without a spontaneous recollection (savoir, Wissen, Al-Elm, Zhi-Dao) of a word that corresponds to her physical image, whereas in knowing the woman I have insight (connaissance, Kenntnis, Al-Ma’rifa, Ren-Shi) into her character. Ambiguous references to knowledge are not resolved in English simply by noting that we are “acquainted” with the person but “unaware” of her name, because the knowledge-distinction being drawn here also refers to objects (i.e., entities without proper names and with which one cannot make acquaintance). Besides sounding somewhat peculiar, asking native English speakers if they are “aware of” versus “acquainted with” how a car works will likely be greeted with a knowing, “Oh, you are asking whether I know how a car works,” but with total naiveté as to whether the knowledge being referred to is one of savoir or connaissance. The newly licensed driver will happily inform the questioner about nuances in turning keys and steering wheels, opening and closing doors, negotiating traffic, and stepping on pedals (i.e., about operational knowledge regarding how to “work” cars). However, the car mechanic will answer the same question in terms of combustion, suspension, and the like (i.e., regarding relational knowledge on how [that is, “the grammar according to which”] cars work). Thus it is insufficient merely to ask how a car works; one must specify whether one’s motivation in asking the question is (exclusively) operational or relational. The second distinguishing characteristic among languages-of-motivation (or modalities) is that each requires a concept of “person” (i.e., of the one who is motivated). As per the above discussion, every modality must stipulate whether utterances regarding people are to be 7 understood as conceptualizations or conceptions. Yet within these utterances, “person” might itself refer to a conceptualization or a conception, or even to the grammar or the immediate sensory experience with which each is respectively associated. • If a conceptualization, is the person … o an objective sequence of immediate conceptualizations potentially at variance with a single expected grammar, or … o the subjective origin of one of many grammars potentially expected as the basis for specific conceptualizations? • If a conception, is the person … o an objective sequence of immediate sensory experiences potentially at variance with a single conception, or … o the subjective origin of one of many conceptions potentially expected as a sensory experience? Note in these questions how the inherently public character of conceptualizations and sensory experiences is contrasted with the inherently private (or subjective) character of grammars and conceptions. That is, private grammars can only be inferred from public conceptualizations, as can private conceptions be inferred from public sensory experiences. With these distinctions in mind, we now have the makings of a language for distinguishing among social theories. Table 1 provides an overview of four types of personhood that have emerged from the preceding discussion. On the one hand, theorists may define “person” as a subjectivity within which private conceptions or a private grammar is maintained. Or they may define “person” objectively as conceptualizations or as sensations immediately accessible to others. On the other hand, theorists’ definitions may regard personhood in terms of its nonexpected différance or its 8 Table 1. Four conceptualizations of personhood “Person” is defined as the . . . subjective origin of objective manifestation of agent persona collaborator follower différance articulation expected articulation. The resulting four definitions of personhood are (as per our above discussion) mutually exclusive, and thus afford us a language for drawing clear distinctions among social theories. Let us label these (now grammatically interrelated) types of person as… • agent—a person whose subjectively-maintained conceptions (or goals) may or may not be objectively achieved at any given moment • collaborator—a person whose subjectively-maintained grammar (or culture) may or may not be objectively articulated at any given moment • persona—a person whose objective performance may or may not correspond to others’ sensory (or role-) expectations • follower—a person whose objective articulations may or may not cohere with others’ grammatical (or normative-) expectations These four types of personhood are most commonly associated with social theorists who respectively refer to themselves as rational choice theorists, functionalists, dramaturgists, and conflict theorists. Each of these four theoretical traditions is universalistic in that it treats all 9 human behavior as manifestations of a single personhood type. 3 Accordingly, many of our readings are grouped under these four headings. Yet not all social theories are universalistic. Instead, four “subversive theories” have emerged during the last half-century—theories that call into question the universalistic assumptions of each respective tradition among the previous four. Critical theorists argue that agents’ goals are themselves the product of their subjection to an ongoing barrage of advertisements. Risk theorists note that even the most devoted collaborators will bring their society to disaster if they fail to consider broader, environmental dangers. Queer theorists suggest ways that audience-expectations can be subverted and changed. Social constructionists point out that even the most appealing universalistic grammar is open to question and doubt. And so four more sections are added to our collection to accommodate these subversive perspectives. The last section of readings is by theorists who accommodate more than one motivational dynamic in their writings. Georg Simmel spent his career writing about forms of sociation (Vergesellschaftungsformen) within which persons with distinct motivations stimulate each other in ways that strengthen these motivations in the self-sustaining ways. Michel Foucault provides numerous illustrations of how people’s motivations vary fundamentally from one historical setting to another. But we are getting ahead of ourselves. These theorists’ insights are a long way from our initial thoughts on language and sensory experience—a long way from the theoretical writings of people like Benjamin Whorf, Mary Douglas, and Jacques Derrida. 3 Randall Collins (1994) should be acknowledged here for suggesting this relatively concise list of sociological traditions. My hope is this that the above discussion affords useful insights into relations among the theories in his list. 10 References Coleman, James. 1990. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. Collins, Randall. 1994. Four Sociological Traditions. New York, NY: Oxford U. Press. Derrida, Jacques. (1967) 1976. Of Grammatology. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins U. Press. Grote, John. 1865. Exploratio Philosophica. Cambridge, UK: Deighton, Bell, & Co. Hamlyn, D. W. 1970. The Theory of Knowledge. Garden City, NJ: Anchor. James, William. (1909) 1955. Pragmatism and Four Essays from The Meaning of Truth. Cleveland, OH: Meridian. Merton, Robert K. 1972. “Insiders and Outsiders: A chapter in the sociology of knowledge.” American Journal of Sociology 78:9-47. Parsons, Talcott. 1951. The Social System. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. Roberts, Carl W. 2008. ‘The’ Fifth Modality: On Languages that Shape our Motivations and Cultures. Leiden, NL: Brill. Sassure, Ferdinand de. (1915) 1983. Course in General Linguistics. La Salle, IL: Open Court. Woozley, A. D. 1969. Theory of Knowledge: An Introduction. London: Hutchinson. 11