INDEPENDENCE PROBABILITY &

advertisement

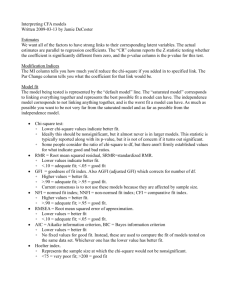

INDEPENDENCE & PROBABILITY A. Before beginning t h i s section, i t i s i m p o r t a n t t h a t a common misunderstanding i s prevented. I f t h i s s e c t i o n i s n o t c a r e f u l l y followed, i t i s easy t o m i s t a k e n l y conclude t h a t (i.e., Pr( A & B ) = Pr( A ) * Pr( B ) t h a t t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t t h e events, A and B, j o i n t l y occur equals t h e product of t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t event A occurs times t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t event B occurs). I n f a c t , f o r any g i v e n sample estimates o f these p r o b a b i l i t i e s a r e u n l i k e l y t o e x a c t l y y i e l d t h i s equivalence. So, f o r t h e record, please keep t h e f o l l o w i n g i n mind: 1. It i s always t r u e t h a t Pr( A & B ) = Pr( A I B ) * Pr( B ) (i.e., that t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t t h e events, A and B, j o i n t l y occur equals t h e product o f t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t event A occurs g i v e n t h a t t h e event B has occurred times t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t event B o c c u r s ) . 2. I n t h e s o e c i a l case when A and B a r e independent events, however, P r ( A & B ) = P r ( A ) * P r ( B ) . B. That said, l e t us now begin w i t h an imaginary p o p u l a t i o n . We draw two u n i t s ( c a l l them Joe and Mary) from t h e p o p u l a t i o n a t random and e v a l u a t e them according t o some c h a r a c t e r i s t i c (e.g., age). (Note t h a t we a r e a s s i g n i n g t h e names, Joe and Mary, i r r e s p e c t i v e o f t h e u n i t s ' a c t u a l names o r genders.) 1. A t t h i s p o i n t we might ask ourselves, "What i s t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t Joe i s o l d e r than t h e mean aqe f o r t h e p o o u l a t i o n ? " On t h e one hand, t h e age d i s t r i b u t i o n might be skewed t o t h e r i g h t ( i . e . , more younger people than o l d e r people). t h e r e may be many I f couples a r e having fewer c h i l d r e n , t h e d i s t r i b u t i o n might be more symmetric (i.e., fewer babies may be "balanced" by t h e number o f o l d e r people from l a r g e b i r t h c o h o r t s On t h e o t h e r hand, i f t h e p o p u l a t i o n i s o f people who have d i e d o f f ) . who a b s t a i n from sex a l t o g e t h e r (e.g., a r e l i g i o u s community l i k e t h a t o f t h e Shakers), t h e age d i s t r i b u t i o n might be skewed t o t h e l e f t . In t h e f i r s t case, t h e p r o b a b i l i t y would be l e s s than . 5 (because t h e p o p u l a t i o n ' s mean age, pA, would be l a r g e r than t h e p o p u l a t i o n ' s median). I n t h e l a s t case, i t would be g r e a t e r than . 5 (because i t would be s m a l l e r than t h e p o p u l a t i o n ' s median). Because t h e median i s t h e value o f a v a r i a b l e such t h a t . 5 o f t h e d i s t r i b u t i o n has h i g h e r values (and . 5 has lower values) on t h e v a r i a b l e , i t i s o n l y i n t h e second case (when t h e d i s t r i b u t i o n i s symmetric and mean=median) t h a t we may conclude t h e f o l l o w i n g : Pr( J ) = .5 , where J i s t h e event t h a t Joe's age > pA . a. The p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t a s i n g l e event occurs i s sometimes r e f e r r e d t o as t h e MARGINAL PROBABILITY o f t h e event. It i s the p r o b a b i l i t y o f an event i r r e s p e c t i v e o f whether o r n o t any o t h e r events may have occurred. b. Note t h a t t h i s use o f t h e P r ( * ) n o t a t i o n i s somewhat d i f f e r e n t from our e a r l i e r usage. The use o f J here (and M, A, B, e t c . l a t e r on) corresponds t o a s p e c i f i c event, n o t u n l i k e t h e d i s c r e t e a t t r i b u t e s o f nominal-level variables. P r i o r references t o Pr( X > k ) allow X t o t a k e values along a continuum, n o t u n l i k e t h e a t t r i b u t e s o f r a t i o - l e v e l variables. 2. O.K. Then l e t ' s assume t h a t Joe and Mary were randomly sampled from a p o p u l a t i o n w i t h a symmetric age d i s t r i b u t i o n . A JOINT PROBABILITY i s t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t two o r more events occur. Accordingly, we might 40 ask, "What i s t h e j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t g r e a t e r t h a n t h e p o p u l a t i o n ' s mean age?" both Joe's and Mary's ages are To h e l p i n answering t h i s question, we can use a 2 x 2 t a b l e t o d e p i c t t h e f o u r r e l e v a n t combinations o f events r e g a r d i n g Joe's and Mary's ages: Joe above be1 ow above Mary below I f Joe and Mary were sampled a t random, then t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t Mary's age i s g r e a t e r than t h e p o p u l a t i o n mean i s independent o f ( i .e., u n e f f e c t e d by) whether o r n o t Joe's age i s g r e a t e r than t h e mean. Note t h a t whenever two events are independent (as are u n i t s o f a n a l y s i s ' s values on v a r i a b l e s a r e when t h e y a r e sampled a t random), t h e j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t i e s o f t h e events equals t h e product o f t h e marginal p r o b a b i l i t i e s o f t h e events. Pr( J & M ) = Pr( J ) Using p r o b a b i l i t y n o t a t i o n , Pr( M ) = .5 . 5 = .25 . Accordingly, t h e j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t y represented by each c e l l i n t h e t a b l e equals . 2 5 . Thus " t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t EITHER Joe's OR Mary's ( b u t NOT BOTH'S) ages are g r e a t e r than t h e mean" can be c a l c u l a t e d as f o l l o w s : NOTICE t h a t t h i s ONLY HOLDS WHEN Joe's and Mary's ages a r e RANDOM events, as t h e y would n o t be were Mary and Joe m a r r i e d t o each o t h e r , f o r example. 3. DEFINITION: Two random variables are s t a t i s t i c a l l y independent i f the "conditional distribution" o f one I s the same within each l e v e l o f the other variable. Thus, i f Joe has one l e v e l o f t h e age v a r i a b l e (e.g., being o l d e r than t h e mean age), t h e p r o b a b i l i t i e s a r e .5 t h a t Mary (when selected) w i l l be younger than t h e mean age and .5 t h a t Mary w i l l be o l d e r than t h i s . I f Joe's l e v e l on t h e age v a r i a b l e i s "younger than t h e mean age," these p r o b a b i l i t i e s remain t h e same (i.e., the conditional d i s t r i b u t i o n o f Mary's age i s t h e same no m a t t e r what Joe's age l e v e l i s ) . Got i t ? C. Knowing a STATISTICAL DEPENDENCE when you see one L e t ' s now consider an example t h a t s h i f t s our t h i n k i n g from p r o b a b i l i t y d i s t r i b u t i o n s f o r two u n i t s o f a n a l y s i s , t o e m p i r i c a l d i s t r i b u t i o n s f o r two groups ( o r c l u s t e r s ) o f these u n i t s . I n examining people's general a n x i e t y about l i f e , you might hypothesize t h a t t h e more r e l i g i o u s people are, t h e l e s s anxious they are. This can be shown g r a p h i c a l l y as f o l l o w s : r e l i ious 4 Not anxious not r e l i ious 4 Very anxious Since t h e d i s t r i b u t i o n o f a n x i e t y i s d i f f e r e n t f o r d i f f e r e n t r e l i g i o s i t y l e v e l s , a n x i e t y and re1 i g i o s i t y a r e s t a t i s t i c a l l v d e ~ e n d e n t . NOTE: I f you assume t h a t each o f these superimposed d i s t r i b u t i o n s are normal, you might wish t o t e s t whether t h e mean a n x i e t y scores o f t h e i r corresponding subpopulations are significantly different. This is what is done when you use a t-test, which we shall discuss at length later in the semester. D. random s a m ~ l i n q so im~ortant 1. Random sampling is a data-collection strategy for ensuring statistical independence of observations among units of analysis (like Mary and Joe). As a consequence, any dependence found in one's data matrix can only have originated in one of two ways: a. On the one hand, the dependence may be due to nonrepresentative peculiarities among the units of analysis randomly selected into the sample. This is what statisticians mean when they speak of results' being due to s a m ~ l i n gerror. Always recognizing this possibility, but armed with the central limit theorem, the statistician estimates the probability that this has occurred. If this probability is sufficiently small (commonly, less than .05), the dependence may have an a1 ternati ve, "nonerroneous" source. b. On the other hand, if one's units of analysis are representative of the population from which they were sampled (i .e., if sampling error is not the culprit), then any statistical dependencies detected in one's sample must reflect de~endenciesamonq variables in this larger population. Accordingly, given that their random sampl ing allows them to assume observations among subjects to be statistically independent, statisticians generally speak of independence and dependence among variables (not subjects). 2. Statisticians tend to think of statistical independence and dependence i n terms o f t h e "random v a r i a b l e s " o f a data m a t r i x . For example, consider t h e f o l l o w i n g m a t r i x w i t h data on "n" u n i t s o f a n a l y s i s and "k" variables: V a r l Var2 Var3 4 2 person $1 2 5 7 . person $2 1 2 4 person $3 3 . . . Vark .... ... .... .. 3 2 3 Each number i n t h i s m a t r i x i s t h e value taken by a RANDOM VARIABLE. Imagine t h a t you have n o t y e t c o l l e c t e d y o u r data and t h a t you have j u s t made plans t o i d e n t i f y t h e a t t r i b u t e s o f "n" persons on "k" v a r i a b l e s . Before c o l l e c t i n g y o u r d a t a you can t h i n k o f y o u r s e l f as having an empty d a t a m a t r i x w i t h n - t i m e s - k place-holders f o r values t h a t w i l l be s e t o n l y once you have randomly selected t h e persons t o be i n c l u d e d i n your sample. These n - t i m e s - k place-holders are t h e random v a r i a b l e s t h a t you have a t y o u r d i s p o s a l . Note how t h e values taken by a " v a r i a b l e " (i.e., t h e values down a column o f t h e m a t r i x ) a r e t h e values taken by t h e "random v a r i a b l e s " associated w i t h i t . Because random sampling ensures t h a t d a t a on persons ( o r , more g e n e r a l l y , on u n i t s o f a n a l y s i s ) a r e s t a t i s t i c a l l y independent, any dependencles found among one's data are most likely due to statistical DEPENDENCE among one's variables and not unong one's subjects! T h i s i s important because researchers a r e g e n e r a l l y NOT i n t e r e s t e d i n p a r t i c u l a r u n i t s o f a n a l y s i s (except i n t h a t they are r e p r e s e n t a t i v e o f t h e i r populations-of-interest). Instead, t h e researcher's o b j e c t i v e i s t o understand a s s o c i a t i o n s ( o r dependencies) amonq v a r i a b l e s . When u n i t s o f a n a l y s i s have been sampled a t random, n o t o n l y does t h e c e n t r a l l i m i t theorem h o l d b u t you have ensured t h a t a s s o c i a t i o n s found i n your d a t a are ones among v a r i a b l e s . I cannot overemphasize t h e importance o f t h i s conclusion. E. Thus f a r i t has been claimed t h a t when two v a r i a b l e s a r e s t a t i s t i c a l l y independent, Pr(A&B) = Pr(A)*Pr(B) . I f A & B are two persons' values on t h e same v a r i a b l e (e.g., age) then t h i s e q u a l i t y h o l d s whenever these persons have been RANDOMLY sampled. F. Now l e t us imagine t h a t we a l s o know t h a t Joe ( t h e f i r s t person sampled) i s C a t h o l i c and t h a t t h e C a t h o l i c s i n o u r p o p u l a t i o n a r e (on t h e average) younger t h a n o t h e r subjects. (Say, t h e y have l o t s o f babies.) Then aiven t h at Joe - i s C a t h o l i c , t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t Mary i s o l d e r than Joe i s g r e a t e r t h a n t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t she i s not-assuming s e l e c t e d a t random from o u r population. t h a t Mary i s L e t ' s t a k e t h i s example more seriously: Each o f t h e f o l l o w i n g i s a CONDITIONAL PROBABILITY ( i . e . , a probability o f an event's occurrence g i v e n your knowledge t h a t an o t h e r event[s] has occurred). Taken together, t h e y b o t h comprise t h e c o n d i t i o n a l d i s t r i b u t i o n o f respondents' above- o r below-mean ages g i v e n t h a t t h e y have Roman Catholic religious a f f i l i a t i o n : ASIDE: The "I" I pA I Pr( X > pA X = Catholic ) Pr( X < X = C a t h o l i c ) = .6 = .4 i n these expressions i s read as "given." For example, t h e f i r s t e q u a l i t y i s read, "Given ( I ) t h a t X i s C a t h o l i c , t h e p r o b a b i l i t y i s . 4 t h a t X has an age g r e a t e r than (>) t h e average age i n t h e p o p u l a t i o n (bA).Ig We can i l l u s t r a t e t h i s u s i n g a VENN DIAGRAM: I f you know t h a t X=Catholic, then you are o n l y l o o k i n g a t a subpopulation o f t h e respondents. The c o n d i t i o n a l p r o b a b i l i t y r e f e r s t o how many o f t h e C a t h o l i c s are o l d vs. young. To f i n d t h e j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t someone i s BOTH o l d and C a t h o l i c r e q u i r e s t h a t we know something more t h a n i s d e p i c t e d i n t h e diagram. I f you are drawing a sample from a p o p u l a t i o n o f C a t h o l i c s , then t h e p r o b a b i l i t y o f sampling a C a t h o l i c i s one. In this case you would be "given" t h a t each u n i t o f a n a l y s i s i s C a t h o l i c , l e a v i n g t h e j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t y o f being b o t h o l d and C a t h o l i c equal t o t h e c o n d i t i o n a l p r o b a b i l i t y o f being o l d g i v e n C a t h o l i c a f f i l i a t i o n . Instead, l e t ' s assume t h a t we a r e s t u d y i n g r e s i d e n t s o f Antwerp and t h a t 70% o f t h e people i n t h i s B e l g i a n c i t y are C a t h o l i c . I.e., we have t h e f o l l o w i n g marginal d i s t r i b u t i o n o f r e l i g i o n : Pr( X = Catholic ) = .7 Pr( X t Catholic ) = .3 Now, l e t us consider t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t someone i s BOTH o l d and C a t h o l i c : 1. I f we make t h e u n l i k e l y assumption t h a t age i s s y m m e t r i c a l l y d i s t r i b u t e d among Antwerp's r e s i d e n t s , we can conclude ( g i v e n t h e d i s c u s s i o n a t t h e o u t s e t o f t h i s s e c t i o n ) t h a t t h e marginal d i s t r i b u t i o n o f age i s as f o l l o w s : 2. B l i n d l y a p p l y i n g t h e formula f o r s t a t i s t i c a l l y independent v a r i a b l e s , we calculate that P r ( X > pA ) Pr( X = C a t h o l i c ) = .5 .7 = .35 . But t h i s i s NOT t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t a respondent i s an o l d C a t h o l i c , equals . 4 ! X > pA i f X = C a t h o l i c , then t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t s i n c e we know t h a t I.e., i t i s NOT .5 Pr( X > pA ) as i s i n the population. So we need t o change o u r formula s l i g h t l y : P r ( X = o l d and C a t h o l i c ) = Pr( X = C a t h o l i c ) = .7 .4 = .28 Pr( X = old I X = Catholic) (which i s c l e a r l y l e s s than .35) We can i l l u s t r a t e these p r o b a b i l i t i e s i n a t a b l e : Table 1: Table o f J o i n t and Marginal P r o b a b i l i t i e s o f R e l i g i o n and Age o f Residents o f Antwerp, Belgium. Re1 i g i o n Catholic other 01d Age Young COMMENTS: a. CONDITIONAL PROBABILITIES are c a l c u l a t e d as f o l l o w s : P r ( X > pA I X = C a t h o l i c ) = . 4 = .28/.70 = Pr( Old a C a t h o l i c ) Pr( Catholic ) X (Recall t h a t i f you know t h a t = Catholic , then you a r e o n l y l o o k i n g a t a subpopulation o f 70% o f t h e t o t a l . To f i n d t h e c o n d i t i o n a l p r o b a b i l i t y o f being o l d g i v e n being C a t h o l i c , you need o n l y ask, "How many o f these 70% are o l d ? " ) Thus, t h e r e l a t i o n among c o n d i t i o n a l , marginal, and j o i n t probabilities i s Conditional . Joint Marginal = NOTE: Be sure you can d i s t i n g u i s h among " j o i n t , " "conditional," and "marginal d i s t r i b u t i o n s " ! ! ! b. P r ( 0 & C ) = Pr( 0 ) Pr( C = Pr( C ) Pr( 0 BUT, n o t e t h a t c. When Pr( 0 & C ) t h e two events, I Pr( C = 0 ) t Pr( C ) 0 & C , are 1 I 0 ) = .5 (.28)/.5 = .28 C ) = .7 (.28)/.7 = .28 Pr( 0 Pr( 0 not I I !!! C ) C ) t Pr( C ) Pr( 0 ) , then s t a t i s t i c a l l y independent: RECALL t h a t s t a t i s t i c a l independence r e q u i r e s t h a t t h e CONDITIONAL DISTRIBUTION o f one v a r i a b l e (e.g., DISTRIBUTION (e.g., (e.s., I Pr( 0 C ) ) equals i t s MARGINAL Pr( 0 ) ) f o r a l l l e v e l s o f a second v a r i a b l e c). d. F i n a l l y , when one v a r i a b l e i s independent o f t h e o t h e r , t h e o t h e r i s s t a t i s t i c a l l y independent o f i t . That i s , Pr( C 1 0 ) Pr( 0 = Pr( C ) implies I Pr( 0 ) . Pr(C)*Pr(O I C ) = T h i s f o l l o w s , s i n c e by d e f i n i t i o n , Pr(O&C) And i f = Pr(O)*Pr(C Pr( C 1 0 ) = Pr( C ) 1 0 ) , then = Pr( 0 I C ) . C ) = Pr( 0 ) ! ! ! G. NOW, THE BIG QUESTION: What i s a knowledge o f marginal, j o i n t , and c o n d i t i o n a l d i s t r i b u t i o n s good f o r ? 1. Imagine t h a t you wish t o draw a m u l t i s t a g e c l u s t e r sample o f r e s i d e n t s from a c i t y o f 60,000. The sample i s t o be drawn i n two stages and w i t h p r o b a b i l i t y ~ r o o o r t i o n a lt o s i z e ( i . . i n a manner e n s u r i n g t h a t each r e s i d e n t has t h e same p r o b a b i l i t y o f being i n c l u d e d i n t h e sample). A sample o f 300 i s t o be obtained by randomly sampling 10 r e s i d e n t s w i t h i n each o f 30 randomly sampled blocks. 2. I n t h e f i r s t stage o f your sampling, you wish t o sample each b l o c k (B) w i t h a p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t ensures t h a t each o f i t s r e s i d e n t s (R) has t h e same chance o f being i n c l u d e d i n t h e f i n a l sample. p r o b a b i l i t i e s can be c o r r e c t l y assigned (e.g., Assuming t h a t these based on census records) and g i v e n your m o t i v a t i o n t o ensure t h a t each o f t h e c i t y ' s 60,000 r e s i d e n t s has t h e same p r o b a b i l i t y o f being i n c l u d e d i n a sample o f s i z e 300, t h i s j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t y o f sampling a r e s i d e n t ' s b l o c k and a r e s i d e n t w i t h i n t h a t b l o c k would be 3. Now, imagine t h a t a b l o c k w i t h 100 r e s i d e n t s i s selected. Given t h a t 10 r e s i d e n t s a r e t o be sampled from each sampled block, t h e p r o b a b i l i t y o f t h e event t h a t one o f these 100 r e s i d e n t s i s i n c l u d e d i n t h e f i n a l sample i s We can g e n e r a l i z e t h i s r e s u l t t o r e f e r t o any b l o c k w i t h an a r b i t r a r y number (say, k ) o f r e s i d e n t s , t o y i e l d t h e c o n d i t i o n a l p r o b a b i l i t y o f t h e event t h a t one o f a b l o c k ' s "k" r e s i d e n t s i s i n c l u d e d i n t h e f i n a l 49 4. Now l e t ' s c o n s i d e r t h e " p r o b a b i l i t y p r o p o r t i o n a t e t o s i z e " question: Given t h e p r o b a b i l i t y a t which you wish each r e s i d e n t t o be s e l e c t e d and t h e p r o b a b i l i t y a t which a r e s i d e n t i s randomly sampled from a b l o c k o f s i z e , k, a t what p r o b a b i l i t y must a b l o c k o f t h i s s i z e be sampled? Here we a r e asking f o r t h e marginal p r o b a b i l i t y a t which t h e 30 b l o c k s a r e t o be sampled. The question's answer f o l l o w s d i r e c t l y from o u r knowledge o f t h e r e l a t i o n among marginal, j o i n t , and c o n d i t i o n a l d i s t r i b u t i o n s : 5. F i n a l comments r e g a r d i n g m u l t i s t a g e c l u s t e r sampling: Once you have found t h e p r o b a b i l i t y a t which blocks a r e t o be sampled, t h e r e i s sampling software t o h e l p you i n sampling b l o c k s "weighted" according t o these p r o b a b i l i t i e s . Also n o t e t h a t b e f o r e doing t h i s , you must ensure t h a t each b l o c k has a t l e a s t 10 r e s i d e n t s ( c a n ' t sample 10 i f t h e r e are o n l y 6) and no more than 2000 r e s i d e n t s (doesn't make sense t o sample a b l o c k a t a p r o b a b i l i t y g r e a t e r than one). l a t t e r p o i n t , t r y c a l c u l a t i n g Pr(B) f o r any I f you a r e u n c l e a r on t h e k > 2000 , and y o u ' l l see what I mean. H. Marginal, j o i n t , and c o n d i t i o n a l p r o b a b i l i t i e s a r e a l s o fundamental t o understanding t h e chi-square s t a t i s t i c . L e t ' s assume t h a t we have obtained a random sample o f 800 Antwerp r e s i d e n t s , and t h a t o u r d a t a are as d e p i c t e d i n Table 2. Based on these d a t a we should be a b l e t o address research questions such as, "Are C a t h o l i c s younger ( o r o l d e r ) than o t h e r r e s i d e n t s ? " Table 2: C a t h o l i c and Non-Catholic Residents by Age.* Religion Catholic Other 01d Age Young 560 * 240 800 H y p o t h e t i c a l data. 1. We can begin answering t h i s q u e s t i o n by determining whether C a t h o l i c s ' ages are d i f f e r e n t from what one would EXPECT ON THE BASIS OF THE MARGINAL AGE DISTRIBUTION OF ALL RESIDENTS. We can e s t i m a t e t h e marginal p r o b a b i l i t i e s associated w i t h being o l d and C a t h o l i c as follows: A Pr( 0 ) = A P r ( C 400 800 = .5 , 560 800 - ' 7 ' =-- A where Pr( 0 ) i s an e s t i m a t o r o f P r ( 0 )t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t an Antwerp r e s i d e n t i s o l d , and where P r ( C ) i s an e s t i m a t o r o f P r ( C )t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h a t an Antwerp resident i s Catholic. A 2. J o i n t p r o b a b i l i t i e s a r e obtained using numbers w i t h i n t h e c e l l s o f the table. For example, 3. Now t o t h e q u e s t i o n a t hand: " I s t h i s j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t y d i f f e r e n t from what one would expect t o f i n d by chance alone (i.e., from what one would expect i f age and r e l i g i o n were i n f a c t u n r e l a t e d among Antwerp residents)?" We can answer t h i s i n p a r t s : a. We know t h a t i f acle and r e l i c l i o n are u n r e l a t e d (a.k.a., independent), P r ( O & C ) = P r ( O ) * P r ( C ) . b. Given t h i s , we can now e s t i m a t e how many o l d C a t h o l i c s would one expect t o f i n d i n t h i s sample ( o f s i z e , n = 800 ) i f age and r e l i g i o n were u n r e l a t e d among a l l Antwerp r e s i d e n t s : 1) Note t h a t t h e j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t y assumed here (i.e., assumption o f independence) equals .35 ( .5 * given the . 7 ) , whereas t h e j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t y estimated from Table 2 i s c o n s i d e r a b l y s m a l l e r than t h i s (namely, .28 as c a l c u l a t e d above). 2) As a d i r e c t consequence, t h i s expected frequency (f,), 280, i s 56 l a r g e r t h a n t h e observed frequency ( f o ) o f 224 i n Table 2. 3) Given one expected frequency (e.g., fe = 280 ) , we can immediately determine a l l t h e o t h e r EXPECTED CELL FREQUENCIES by ensuring t h a t c e l l frequencies add up t o t h e t a b l e ' s marginal frequencies: Table 3: Expected Frequencies o f C a t h o l i c and Non-Catholic Residents by Age. Re1 i g i o n Other Cathol ic 01d Age Young 4. O.K. Now we know b o t h t h e expected and observed c e l l frequencies associated w i t h o u r sample. BUT how d i f f e r e n t do these frequencies have t o be t o be SIGNIFICANTLY DIFFERENT? T h i s q u e s t i o n i s answered w i t h t h e CHI-SQUARE s t a t i s t i c . C a l c u l a t i n g chi-square r e q u i r e s t h a t f o r each c e l l o f your t a b l e , you f i r s t s u b t r a c t t h e expected from t h e observed c e l l size, t h e n square t h e d i f f e r e n c e , and d i v i d e t h i s by t h e expected c e l l size. these CONTRIBUTIONS distribution. TO The sum o f a l l CHI-SQUARE has a s p e c i f i c p r o b a b i l i t y I n p a r t i c u l a r , t h e sum i s d i s t r i b u t e d as c h i - s q u a r e w i t h t h e number o f degrees o f freedom i n your t a b l e . The formula f o r c h i - square i s as f o l l o w s : # cells Chi-square = x2 ( f o - fe) 2 = a. There i s o n l y one degree o f freedom i n a 2x2 t a b l e . As mentioned p r e v i o u s l y , t h i s i s because i f you know t h e frequency i n 1 c e l l , you can determine t h e frequencies o f a l l o t h e r c e l l s based on b o t h t h i s frequency and t h e marginal frequencies o f t h e t a b l e . I n general, you can decide how many degrees o f freedom you have by u s i n g t h e formula, ( r - 1) where * (c - 1) , r = t h e number o f rows i n t h e t a b l e columns i n t h e t a b l e . and c = t h e number o f I f you added a t h i r d v a r i a b l e w i t h "d" a t t r i b u t e s t o t h e t a b l e , t h e r e s u l t i n g 3-dimensional t a b l e would have ( r - 1) * (c - 1) * (d - 1) degrees o f freedom. T h i s can be general i z e d f u r t h e r . b. O.K., so we c a l c u l a t e i t and d i s c o v e r t h a t c h i - s q u a r e = 74.67 . Now what? - Well, we want t o know i f C a t h o l i c s a r e younger t h a n we would To f i n d out, we l o o k a t expect on t h e b a s i s o f t h e marginals alone. Table C from among t h e t a b l e s handed o u t i n c l a s s . There i t i n d i c a t e s t h a t i n a t a b l e w i t h 1 degree o f freedom, Pr( x12 > 10.827 ) = .001 . 1) Whereas i n t h e standard normal t a b l e (Table A) t h e body o f t h e t a b l e c o n t a i n s p r o b a b i l i t i e s and values o f t h e z - s t a t i s t i c head t h e rows and columns, i n your c h i - s q u a r e t a b l e (Table C) t h e body o f t h e t a b l e c o n t a i n s values o f t h e c h i - s q u a r e - s t a t i s t i c , columns a r e headed by p r o b a b i l i t i e s , and rows a r e headed by "degrees o f freedom" f o r your t a b l e . 2) Because our c h i - s q u a r e o f 74.67 i s (considerably) l a r g e r than t h i s , t h e p r o b a b i l i t y i s l e s s than .001 t h a t sampling e r r o r accounts f o r why o u r observed frequencies d i f f e r so much from t h e frequencies we would have expected i f age and r e l i g i o n were s t a t i s t i c a l l y independent. T h i s i s because i t i s v e r y u n l i k e l y t h a t t h e c h i - s q u a r e o f 74.67 r e f l e c t s a chance occurrence due t o p e c u l i a r i t i e s o f o u r sample. I.STATISTICAL SIGNIFICANCE versus THEORETICAL CONFIRMATION 1. Once you know t h a t a t a b l e c o n t a i n s a s t a t i s t i c a l l y s i g n i f i c a n t a s s o c i a t i o n , you s t i l l do n o t know i f t h e a s s o c i a t i o n i s i n t h e hvoothesized d i r e c t i o n . For example, c h i -square c o u l d equal 74.67 because C a t h o l i c s a r e s i g n i f i c a n t l y older than non-Catholics. So i t i s o n l y by r e t u r n i n g t o t h e t a b l e t h a t we can d e f i n i t i v e l y e s t a b l i s h whether C a t h o l i c s are s i g n i f i c a n t l y younger than non-Catholics. above case we can conclude t h a t t h e y are, because 54 I n the 2. One o f t h e most common among mistakes made by s o c i a l s c i e n t i s t s i s t o conclude t h a t a s t a t i s t i c a l l y s i g n i f i c a n t f i n d i n g supports t h e i r t h e o r y d e s p i t e t h e f a c t t h a t ( w i t h o u t t h e i r having n o t i c e d i t ) t h e d i r e c t i o n o f t h e s i g n i f i c a n t a s s o c i a t i o n i s o ~ o o s i t et o t h a t suggested i n t h e i r theory. Please be c a r e f u l n o t t o mistake s t a t i s t i c a l s i c l n i f i c a n c e for theoretical confirmation. J. STATISTICAL SIGNIFICANCE versus SUBSTANTIVE IMPORTANCE IMAGINE that o u r d a t a on t h e Belgian c i t y a r e as f o l l o w s : Table 4: C a t h o l i c and Non-Catholic Residents by Age.* Religion Cathol i c Other Old Age Young * 560 H y p o t h e t i c a l data. 240 800 The t a b l e shows C a t h o l i c r e s i d e n t s seven percent (7%) more l i k e l y t o be young t h a n r e s i d e n t s w i t h o t h e r r e l i g i o u s a f f i l i a t i o n s . 1. I s t h i s s t a t i s t i c a l l v s i q n i f i c a n t ? Yes, i t i s ( a t c a l c u l a t e d value o f chi-square equals than x12 4.02 , a = .05 ) . The which ( s i n c e i t i s l a r g e r .05 = 3.841 [see Table C]) i n d i c a t e s t h a t a r e s u l t t h i s s t r o n g o r s t r o n g e r would occur by chance i n o n l y one same-sized random sample i n twenty. 2. I s t h e r e s u l t SUBSTANTIVELY IMPORTANT? What do you t h i n k ? a. THERE I S NO STATISTICAL BASIS FOR DECIDING how much o f a d i f f e r e n c e i s s u b s t a n t i v e l y important. You must c o n s u l t your theory, your colleagues, and your common sense. b. Using t h e .05 s i g n i f i c a n c e l e v e l and c o n s i d e r i n g a 10% d i f f e r e n c e t o be s u b s t a n t i v e l y important, t h e f i n d i n g s i n Table 4 a r e s t a t i s t i c a l l y significant, but not s u b s t a n t i v e l y important. Because s t a t i s t i c i a n s ( l i k e you) must decide what i s s u b s t a n t i v e l y important, t h e i r s t a t i s t i c s a r e unable t o "speak f o r themselves." K. RELATING CHI-SQUARE BACK TO THE CONCEPT OF "STATISTICAL INDEPENDENCE": L e t ' s see j u s t what we have done here. We have two events, 0 = t h e event o f being " o l d " and C = t h e event o f being C a t h o l i c . data, t h e y a r e i n t h i s form: When we c o l l e c t o u r Table 5: Dummy Table o f C a t h o l i c s and Old Residents. - C C The question i s , then, whether o r n o t 0 and C a r e s t a t i s t i c a l l y independent. To decide t h i s , we need o n l y f i n d o u t i f Pr( 0 (i.e., a C ) = Pr( 0 ) Pr( C ) i f t h e j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t y o f 0 and C equals t h e product o f t h e marginal p r o b a b i l i t i e s o f t h e events 0 and C). 1. The marginal p r o b a b i l i t i e s o f 0 and C are estimated as f o l l o w s : 2. The j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t y of 0 and C i s estimated as f o l l o w s : 3. Thus, a good t e s t o f s t a t i s t i c a l independence should e v a l u a t e whether Pr(O&C)=Pr(O)*Pr(C) . I n terms o f our dummy t a b l e , i t should evaluate t h e e x t e n t t h a t P(; 0 o r that a C ) = P(; a 7 = 0 ) a + b n P(; C ) a + c n RECALL t h a t i n c a l c u l a t i n g chi-square, we sum up For t h e a - c e l l i n Table 4, t h e observed frequency i s t h e expected frequency i s So, t h e c o n t r i b u t i o n to fe = a + b n a + c n * n fo = a and . chi-sauare o f t h e a - c e l l i s M u l t i p l y i n g by we g e t l/n2 T h i s i s t h e CONTRIBUTION o f c e l l "a" t o chi-square i n a t w o - v a r i a b l e table. A few COMMENTS about t h i s " c o n t r i b u t i o n " are i n order: a. The magnitude o f t h e c o n t r i b u t i o n meets one important c r i t e r i o n o f a good t e s t o f s t a t i s t i c a l independence, since i t equals zero when A Pr(08C) = a 7 = a + b n a + c n A = Pr( 0 ) A Pr( C ) b. I n a t h r e e - v a r i a b l e t a b l e t h i s c o n t r i b u t i o n would l o o k l i k e t h i s : . T h i s can be g e n e r a l i z e d f u r t h e r . c. NOTICE how t h e 'n' i n t h e formula f o r t h e c o n t r i b u t i o n suggests t h a t t h e l a r g e r one's sample size, t h e more l i k e l y a s t a t i s t i c a l l y A s i q n i f i c a n t d i f f e r e n c e between Pr( 0 ) * A Pr( C ) and A Pr( 0 & C ) w i l l be detected. L. About t h e chi-square d i s t r i b u t i o n 1. Chi-square and sample s i z e a. We have a 2 x 2 t a b l e : We now can estimate t h e p r o b a b i l i t y t h i s happened by chance. Table C, we f i n d t h a t Pr( x12 > 1.074 ) = .30 . From (Note t h a t 1.074 i s as c l o s e t o our c h i - s q u a r e o f .95 as we can f i n d i n Table C.) Thus ( u s i n g a b i t o f mental i n t e r p o l a t i o n ) , t h e p r o b a b i l i t y o f g e t t i n g a c h i - s q u a r e as l a r g e as .95 & chance i s about .34 . That i s , one would expect a c h i - s q u a r e t h i s l a r g e o r l a r g e r i n about one o u t o f (l.e., every t h r e e t a b l e s t h i s s i z e . i t i s VERY probable.) b. Now, a l l o t h e r t h i n g s remaining equal, imagine t h a t we have a sample 59 t e n times as l a r g e : From Table C we f i n d t h a t Pr( x12 > 10.827 ) = .001 and Pr( x12 > 6.635 ) = .O1 . Again u s i n g a b i t o f mental i n t e r p o l a t i o n , we can conclude t h a t Pr( x12 > 9.5 ) = .004 ( o r SO). That i s , t h e p r o b a b i l i t y o f g e t t i n g a t h i s large & chance i s about 4 i n 1,000 samples ( i e . , NOT probable a t a l l ) . NOTE t h a t t h i s chi-square i s e x a c t l y 10 times as l a r g e as t h e f i r s t one and i s based on a sample e x a c t l y 10 times l a r g e r . coincidence.) I f two t a b l e s have t h e same ( T h i s i s no r e l a t i v e c e l l sizes, b u t one i s based on a sample k times as l a r g e , t h e c h i - s q u a r e f o r t h e l a r g e r t a b l e w i l l be k times t h a t o f t h e s m a l l e r . (An a l g e b r a i c p r o o f o f t h i s statement i s g i v e n on page 58.) c. We can make use o f t h i s i n s i g h t by addressing a new question: How l a r g e a sample would we need f o r t h e same r e l a t i v e c e l l s i z e s t o be detected as s t a t i s t i c a l l y s i g n i f i c a n t a t t h e .05 l e v e l ? We know t h e f o l l o w i n g : 20 i s t h e o r i g i n a l sample s i z e . .95 i s t h e chi-square f o r t h i s sample. 3.841 i s t h e s i z e o f chi-square we need t o d e t e c t . Since 20 k = n and .95 k = 3.841 , then k = 4.04 and n = 81. 2. Chi-square should o n l y be used when fe 5 i n a l l c e l l s o f a 2x2 t a b l e . When one's t a b l e i s l a r g e r than 2x2, 75% o f t h e t a b l e ' s c e l l s should have fe25 and a1 1 c e l l s should have f,>l.l If fe < 5 f o r t o o many c e l l s , then F i s h e r ' s exact t e s t ( f o r 2x2 t a b l e s ) o r an e x t e n s i o n o f t h i s t e s t ( n e i t h e r covered i n t h i s course) should be used. Moreover, l a r g e r expected c e l l s i z e s can be ensured by dropping o r c o l l a p s i n g t h e t a b l e ' s c a t e g o r i e s , o r by c o l l e c t i n g more data. 3. T r i v i a a. The shaoes o f c h i -sauare d i s t r i b u t i o n s change w i t h d i f f e r e n t degrees o f freedom. When t h e degrees o f freedom g e t l a r g e r than 20 o r so, chi-square takes on t h e shape o f a normal d i s t r i b u t i o n . b. The MEAN o f a chi-square d i s t r i b u t i o n equals i t s degrees o f freedom; i t s VARIANCE equals t w i c e i t s degrees o f freedom ( i .e., Var( 2 xdf ) = 2*df ) . c. I f Z - N(0,l) , then Z2 - c h i - s q u a r e w i t h one degree o f freedom. can v e r i f y t h i s by comparing Table A w i t h Table C. Pr( IZI > 1.96 ) = .05 = Pr( x12 -= Z 2 > 3.84 = For example, 11.961 2 ) . Alan A g r e s t i and Barbara F i n l a y . 1986. S t a t i s t i c a l Methods f o r t h e S o c i a l Sciences, 2nd e d i t i o n . San Francisco, CA: Dellen, p. 207. 61 You (NOTE: "1" means "equals by d e f i n i t i o n . " ) ALSO t h e sum o f two squared standard normal random v a r i a b l e s i s d i s t r i b u t e d as a c h i - s q u a r e random v a r i a b l e w i t h TWO degrees o f freedom. T h i s can be g e n e r a l i z e d f u r t h e r t o sums o f more squared standard normal random variables. M. One f i n a l example: You have a contingency t a b l e w i t h f o u r v a r i a b l e s : Religious a f f i l i a t i o n : Gender: Political affiliation: Ethnicity: C a t h o l i c , P r o t e s t a n t , Jewish, Buddhist. Ma1e, Female . Republican, Democrat, Independent, Other. Black, White, Other. 26 We c a l c u l a t e a c h i - s q u a r e f o r t h e t a b l e and i t equals c h i - s q u a r e does NOT p r o v i d e s i g n i f i c a n t evidence ( a t . This value o f a = .05) t h a t t h e d a t a i n t h i s t a b l e v a r y s i g n i f i c a n t l y from what you would expect by chance. Drawing t h i s c o n c l u s i o n begins by determining t h a t t h e a p p r o p r i a t e degrees o f freedom f o r t h i s t a b l e equal 18 ( ] ). = = [ 4-1 ] 2 x18, a xi8 t h i s Then c o n s u l t i n g Table C, we f i n d t h a t 28.869 samples. . Accordingly, one would expect [ 2-1 ] - [ 4-1 ] 25.989 and [ 3-1 x2 ~ ~ l a r g e i n about 1 i n 10 , . ~ N. GENERAL CONCLUSIONS 1. Normal d i s t r i b u t i o n a. I n d i c a t e s t h e p r o b a b i l i t i e s o f random f l u c t u a t i o n s around a p o p u l a t i o n parameter. b. The l a r g e r one's sample (n), t h e more c l o s e l y t h e sampling d i s t r i b u t i o n o f each unbiased p o i n t - e s t i m a t e - s t a t i s t i c w i l l approximate a normal d i s t r i b u t i o n w i t h a mean o f t h e p o p u l a t i o n parameter--the one t h a t t h e s t a t i s t i c estimates-and w i t h a variance t h a t i s i n v e r s e l y p r o p o r t i o n a l t o t h e sample s i z e . 2. Chi-square d i s t r i b u t i o n a. I n d i c a t e s t h e p r o b a b i l i t i e s o f SQUARED random f l u c t u a t i o n s around a p o p u l a t i o n parameter. (Recall t h a t Z2 - c h i - s q u a r e w i t h one degree o f freedom, t h a t t h e sum o f two squared standard normal random v a r i a b l e s i s d i s t r i b u t e d as a c h i -square random v a r i a b l e w i t h two degrees o f freedom, e t c . ) I n t h i s sense, t h e chi-square d i s t r i b u t i o n a l l o w s you t o determine whether you have a "normal" amount o f variation. D i f f e r e n t l y put, c h i -square measures t h e degree t o which y o u r a c t u a l data vary from what you would expect knowing o n l y your marginal d i s t r i b u t i o n s . b. The l a r g e r one's sample (n), t h e l a r g e r the value o f chi-square f o r any g i v e n set o f j o i n t p r o b a b i l i t i e s . I n f a c t a l l t h i n g s equal, i n c r e a s i n g one's sample s i z e by a f a c t o r o f "k" w i l l increase c h i square by e x a c t l y t h i s amount. That i s , whereas p o i n t - e s t i m a t e - s t a t i s t i c s approach p o p u l a t i o n parameters' values f o r i n c r e a s i n g l y l a r g e r samples, c h i - s q u a r e - s t a t i s t i c s approach i n f i n i t y . 63 These two d i s t r i b u t i o n s a r e t h e most important i n a l l o f s t a t i s t i c a l theory. As do a l l p r o b a b i l i t y d i s t r i b u t i o n s , they a l l o w us t o make p r o b a b i l i s t i c statements about i n t e r r e l a t i o n s among v a r i a b l e s when these v a r i a b l e s measure a t t r i b u t e s o f randomly s a m ~ l e dsubjects ( o r o t h e r u n i t s o f analysis).