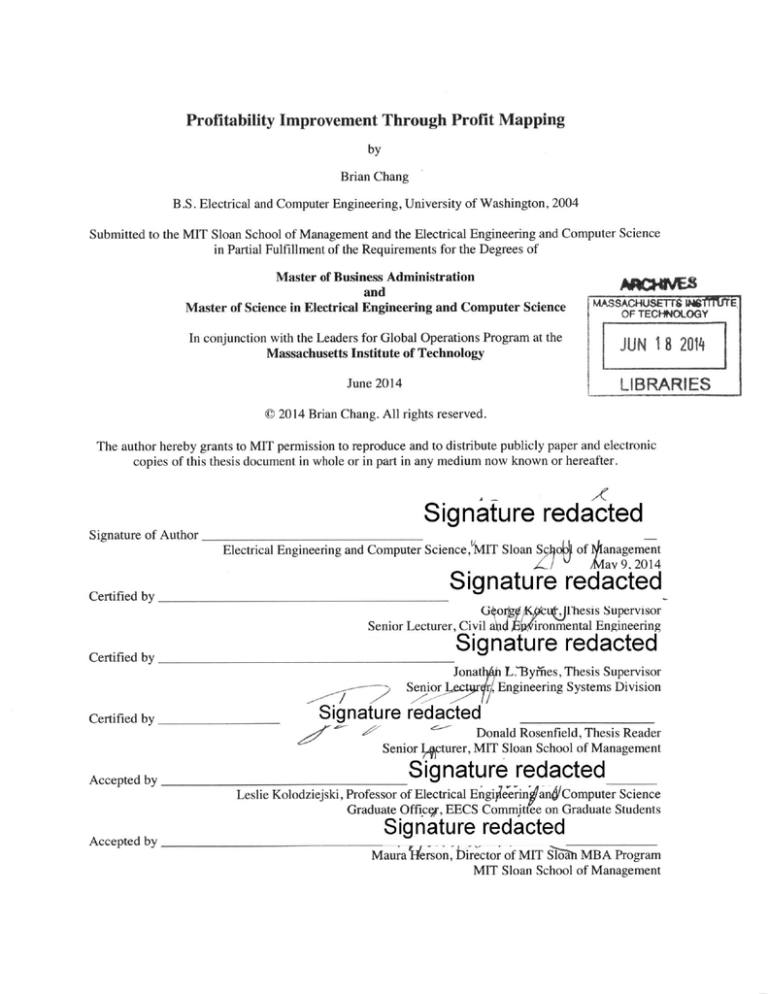

Profitability Improvement Through Profit Mapping

by

Brian Chang

B.S. Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Washington, 2004

Submitted to the MIT Sloan School of Management and the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of

Master of Business Administration

and

Master of Science in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

MASSACHU

In conjunction with the Leaders for Global Operations Program at

the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

JUN 1-8 2014

June 2014

LIBR)ARIES

0 2014 Brian Chang. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic

copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter.

Signature redacted

Signature of Author

of anagement

Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, MIT Sloan Sc)

.nl Iav 9, 2014

Certified by

_________________Signature

redacted

ucjIhesis Supervisor

G~o

Senior Lecturer, Civil a-4iipironmental Engineering

Signature redacted

Certified by

SuCertified by

Senior

Jonatp L.~Bynies, Thesis Supervisor

Engineering Systems Division

Sinaur redacted

_______

Donald Rosenfield, Thesis Reader

Senior Icturer, MiT Sloan School of Management

4:::_

Accepted by

Signature redacted

Leslie Kolodziejski, Professor of Electrical Engieeringan4IComputer Science

Graduate Officq, EECS Commit ee on Graduate Students

Accepted by

M4OLOGY

Signature redacted

Maura Verson, birector of MIT S'n MBA Program

MIT Sloan School of Management

This page intentionally left blank.

2

Profitability Improvement Through Profit Mapping

by

Brian Chang

Submitted to the MIT Sloan School of Management and the Department of Electrical Engineering and

Computer Science on May 9, 2014 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of Master of

Business Administration and Master of Science in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

Abstract

Faced with a dynamically changing market, Boston Scientific's Cardiac Rhythm Management is seeking

ways to increase its profitability. The division is experiencing a phenomenon where pulse generators and

leads' product life cycle transitions may be slower than ideal. In addition, Boston Scientific is exploring

ways to systematically and accurately assess its products' return on investments.

The approach to the project is a technique called Profit Mapping. By carefully assessing the true full costs

of each transaction, we can determine the actual profitability of each account and product and use the

visualized results to detect anomalies, test hypotheses, and formulate action plans.

The profit mapping tool allows us to compare profitability within each dimension of the businessindividual product, account, sales person, territory, contract group, therapy system, or any combination of

multiple dimensions. When we group data by accounts, we discover accounts that generate much higher

profit than accounts that have higher revenue. Profit Map also shows some products or therapies

traditionally believed to be unprofitable are actually high profit earners. Furthermore, time analysis of

account profit maps revealed accounts whose revenue has been on the decline but profit on the rise thanks

to transition in product mix.

The delivery of the framework and its methodology concludes my internship but is only the beginning of

Boston Scientific's journey to increase profitability. The Finance Department can now combine Profit

Mapping data with the Sales Operations Department's experience and instincts to identify best practices

that contribute towards higher revenue dollar efficiency, re-align sales incentives with company's

profitability, and re-evaluate the opportunity cost of maintaining a marginal or net-loss account/product. In

the long run, Profit Mapping can be scaled up to analyze world-wide data from all divisions to provide a

clearer path to profitability.

Thesis Supervisor: George Kocur

Title: Senior Lecturer, Civil and Environmental Engineering

Thesis Supervisor: Jonathan L. Byrnes

Title: Senior Lecturer, Engineering Systems Division

3

This page intentionally left blank.

4

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following people and organizations for making my time at MIT an exceptional

experience.

First of all, I wish to thank MIT's Leaders for Global Operations program for its support of this work.

I would also like to thank Boston Scientific for providing me the internship and the opportunity to learn

from its talents. My internship at Boston Scientific is its first project working with the LGO program, so I

am especially grateful that Boston Scientific is willing to take a chance with me. I certainly hope that the

internship has generated some value for both sides, and that Boston Scientific chooses to continue

partnering with LGO's many qualified talents on future projects. I want to give special thanks to my

project champion, Steve Schiveley, project supervisor, Mark Powers, and my mentor, Alex Shrom, for all

the support in lending their time and resources towards the success of the project. Without them, my

project at Boston Scientific would not have been as enjoyable and exciting as it has been.

I want to thank my MIT faculty advisors, Dr. Jonathan Byrnes and Dr. George Kocur. They provided

enormous help in shaping and guiding the direction of the project at Boston Scientific. The majority of

my work was based on the profit mapping technique described in Dr. Byrnes' book, "Islands of Profit in a

Sea of Red Ink." They have gone out of their way to ensure my time at Boston Scientific was both

valuable to the company and my education, and I am thankful of that.

Most importantly, I want to thank my family for being supportive of my participation in the MIT LOG

Program. And a special thanks to my wife, Tracie, for being very supportive of my internship in

Minneapolis while she is pregnant in Boston. I am glad that you can share my happiness. My education at

MIT has been most rewarding, and I wish to share my exciting future with you.

5

This page intentionally left blank.

6

Table of Contents

A bstrac t ......................................................................................................................................................... 3

Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... 5

Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 7

List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................. 10

List of Tables .............................................................................................................................................. I I

G lo ssary ...................................................................................................................................................... 12

1

2

3

Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 13

1.1

Problem Statement ...................................................................................................................... 13

1.2

The Hypothesis ........................................................................................................................... 13

Background ......................................................................................................................................... 14

2.1

Cardiac Rhythm M anagement Therapies .................................................................................... 14

2.2

Boston Scientific's CRM Division ............................................................................................. 15

2.3

Profit M apping ............................................................................................................................ 15

2.3.1

Profit Map M odel ................................................................................................................ 15

2.3.2

Profit Levers ........................................................................................................................ 17

2.3.3

Profitability M anagement Process ...................................................................................... 18

Profit M ap ........................................................................................................................................... 19

3.1

Profitability Database .................................................................................................................. 19

7

3.1.1

Cost Assignment Philosophy .............................................................................................. 20

3.1.2

Scope for Data Gathering .................................................................................................... 21

3.1.3

Invoices ............................................................................................................................... 22

3.1.4

Cost of Goods Sold ............................................................................................................. 23

3.1.5

Selling Cost ......................................................................................................................... 23

3.1.6

Research & Development Cost ........................................................................................... 27

3.1.7

Period Expense .................................................................................................................... 29

3.1.8

Distribution ......................................................................................................................... 29

3.1.9

Administration and Others .................................................................................................. 30

3.2

Profit Map Configuration ............................................................................................................ 30

3.2.1

X and Y Metrics .................................................................................................................. 31

3.2.2

Aggregator/s ........................................................................................................................ 33

3.2.3

Filter .................................................................................................................................... 33

3.2.4

Metrics Table ...................................................................................................................... 33

3.3

Technical Challenges .................................................................................................................. 34

3.3.1

Automated vs M anual W ork ............................................................................................... 34

3.3.2

Moving Averages ................................................................................................................ 36

3.3.3

Returns ................................................................................................................................ 38

8

4

5

Profit Levers ........................................................................................................................................ 40

4.1

Aggregate by Customer .............................................................................................................. 40

4.2

Aggregate by Customer and Therapy ......................................................................................... 45

4.3

Aggregate by Product Category .................................................................................................. 48

4.4

Trend Analysis ............................................................................................................................ 48

Conclusions and Recommendations ................................................................................................... 50

5.1

Strategy ....................................................................................................................................... 50

5 .2

P e op le .......................................................................................................................................... 5 1

5.3

Structure ...................................................................................................................................... 51

5.4

Process ........................................................................................................................................ 52

5.4.1

Generate/Review Profitability Initiatives ............................................................................ 52

5.4.2

Account/Product/Supplier M anagement ............................................................................. 52

5.5

Reward ........................................................................................................................................ 54

5.6

Conclusion .................................................................................................................................. 55

Bibliography ............................................................................................................................................... 56

9

List of Figures

Figure 1: Profit M ap Overview Example................................................................................................

Figure 3: Stage

-

17

Build Profitability Database.........................................................................................20

Figure 4: Stage 2 - Profit M ap Configuration ........................................................................................

31

Figure 5: Profit M ap Configuration U ser Interface...............................................................................

32

Figure 6: M etrics Table Template...............................................................................................................33

Figure 7: Profit M ap by Customers.........................................................................................................

40

Figure 8: Islands of Profit Customers View ...........................................................................................

42

Figure 9: M innows Customer View .......................................................................................................

44

Figure 10: Profit M ap by Customer-Therapy ........................................................................................

45

Figure 11: Islands of Profit Customer-Therapy View.............................................................................

47

10

List of Tables

1: Invoice Colum ns ...........................................................................................................................

22

Table 2: CO G S Lookup Table ....................................................................................................................

23

Table 3: Regional Expense .........................................................................................................................

25

Table 4: Fixed Selling Cost Calculation Exam ple ..................................................................................

26

Table 5: Service Cost Calculation Exam ple ...........................................................................................

27

Table 6: R& D Projects' Product Category and Spending ........................................................................

29

Table 7: R& D per U nit Calculation Exam ple .........................................................................................

29

Table 8: Exponential Sm oothing Exam ple .............................................................................................

37

Table 9: Moving Average vs Exponential Smoothing vs Unsmoothed R&D Costs ...............................

38

Table 11: Custom ers' Profitability Ranking by Q uarters .......................................................................

49

Table

11

Glossary

CRM - Cardiac Rhythm Management

GPO - Group Purchasing Organization

Brady - Bradycardia

Tachy - Tachycardia

HF - Heart Failure

CRT-P - Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Pacemaker

CRT-D - Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Defibrillator

LDS - Lead Delivery System

COGS - Cost of Goods Sold

R&D - Research and Development

SKU - Stock Keeping Unit

AD - Area Director

RM - Regional Manager

FSR - Field Sales Rep

FCR - Field Clinical Rep

OR - Operating Room

EAI - Enterprise Application Integration

ETL - Extract-Transform-Load

CPO - Chief Profitability Officer

12

1

1.1

Introduction

Problem Statement

Boston Scientific's Cardiac Rhythm Management (CRM) Division is seeking ways to combat

downward pressure on its profitability. The pressure it faces comes from two directions: fiercer

competition and stronger buying power by large group purchasing organizations (GPOs). Boston

Scientific's CRM Division has been experiencing more competition domestically and abroad from its two

main competitors: St. Jude Medical and Medtronic. The commoditization process creates a downward

pressure on the average sales price of the products, and the fight for market share gives large group

purchasing organizations more buying power to negotiate even lower prices. How to maintain or even

raise profitability in the face of 3-5% annual price erosion becomes the CRM Division's priority.

1.2

The Hypothesis

Boston Scientific's CRM Division is taking numerous measures to raise profitability, including

cost cutting, innovating superior products, and others. One of the measures being explored is Profit

Mapping, a technique developed by Dr. Jonathan L. Byrnes, to help businesses (1) identify their sweet

spots (high profits) and focus their resources on securing and maximizing that part of the business; and

(2) find ways to improve the profitability of other parts of the organization. The technique has proven to

be effective in different industries, geographies, and sizes of the business. The hypothesis of this thesis is

that Profit Mapping can be used at Boston Scientific as a tool to test assumptions, discover root causes of

symptoms, identify misalignments in incentives, and evaluate and improve business with the right

metrics.

13

2

2.1

Background

Cardiac Rhythm Management Therapies

Cardiac Rhythm Management therapies aim at treating cardiac dysrhythmia, conditions in which

the heart rate is too fast, too slow, or irregular. The most common cardiac dysrhythmia conditions are:

bradycardia (brady), tachycardia (tachy), heart failure (HF), and/or any combination of them.

Bradycardia is the condition where the patient's resting heart rate is below 60 beats per second.

Most brady patients receive a pacemaker system implant that helps regulate the heartbeat. These surgical

procedures usually take less than an hour. Pathological tachycardia is the condition where the heart enters

a state of uncoordinated rhythm, or fibrillation, often measured as a resting heart rate in excess of 100

beats/minute. Patients exhibiting indications which suggest such a heart condition are often prescribed an

implantable defibrillator system. When the patient enters tachycardia, the defibrillator will take less than

30 seconds to charge the capacitor and release an electric shock to the heart, resetting the heart to normal.

Patients who have both tachy and brady only need the defibrillator implant as it is also capable of

regulating heartbeat. Heart failure, in the context of this thesis, describes a chronic symptom where one

ventricle overworks and enlarges over the years, eventually leading to fatality. HF patients are treated

with either a Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Pacemaker (CRT-P) system or Cardiac

Resynchronization Therapy Defibrillator (CRT-D) system.

Regardless of which therapy a patient receives, a system will consist of three components: the

pulse generator, the leads, and the lead delivery system. The pulse generator is a hermetically sealed can

that contains the battery, computer chip, and capacitor (for defibrillators) that regulates the heartbeat. The

leads are the wires that connect the pulse generator and the heart and transfer the electric signals. Finally,

the lead delivery system (LDS) are the specialized accessories that aid surgeons in delivering the leads

through the veins to the heart. In addition, an optional communication device, Latitude, can be installed in

a patient's bedroom to provide more convenient and closer monitoring of the patient and the device's

14

conditions. Latitude can regularly collect the implanted device's data wirelessly and transmit this

information back to Boston Scientific's database, which can be accessed by the patients' health care team.

2.2

Boston Scientific's CRM Division

The CRM Division is one of the core businesses at Boston Scientific with an annual revenue close

to two billion dollars, making up more than a quarter of Boston Scientific's total revenue. The CRM

Division is based in Arden Hills, Minnesota.

Boston Scientific's Operations Division has three facilities worldwide responsible for the

manufacturing and logistics of the CRM systems. The facility in Dorado, Puerto Rico, manufactures most

of the leads; the plant in St. Paul, Minnesota, manufactures the subassemblies for the leads and PGs; and

the facility in Clonmel, Ireland, manufactures the PGs and performs testing and packaging. Clonmel's

facility also serves as the distribution center for non-US markets, while the US market is being fulfilled

from the distribution center in Arden Hills.

2.3

Profit Mapping

Profit Mapping is a technique developed by Professor Jonathan L. Byrnes. It has three major

components: profit map model, profit levers, and profitability management process. Profit map identifies

the company's profit landscape on a very granular basis; profit levers generate recommendations and

action plans; and profitability management process keeps track of the implementation and the continuous

improvement of profitability. Profit mapping is incomplete without any of these three elements.

2.3.1

Profit Map Model

A profit map is a visualization of where the company's revenue dollars are coming from and where

the profit dollars are coming from. In a typical company, most of the revenues are generated by a small

subset of the entire business, be it customer, product, or sales force, and most of the profits are also

generated by a small subset of the business. However, many companies compensate their sales force

based on revenue numbers instead of actual profit to the company. That is why we need a picture that can

15

identify which parts of the business are the bread and butter that bring in large revenue and large profit,

which ones are small fish with low revenue and low or negative profit, which parts of the business do we

under-compensate, and which ones we over-compensate.

Profit maps are generated with a backend profitability database and a frontend visualizer. The

profitability database needs to show revenues and costs at the invoice level because that allows us to

rebuild the financial picture at any higher aggregated level. At the same time, the database needs to reflect

the full cost, as opposed to just the marginal cost, of each transaction. Marginal costs often lead people to

believe parts of the business to be more profitable than they really are. That is why it is necessary to

assign the expenses on the P&L to the invoices. This is a very important refinement of the general

technique of value stream mapping.

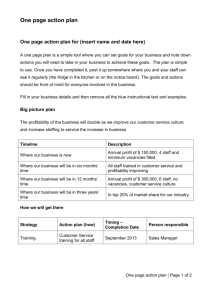

The frontend visualizer allows the user to specify the configuration of the profit map, massages the

profitability database, and outputs a profit map (see Figure 1). Let us first establish the definitions for the

key words used in the configuration of a profit map. The profit map illustrated in is built with data from a

subset of the US domestic CRM business, namely the Southern New England and Boston regions. A

profit map can be thought of as a 2-D Pareto chart, with the X-metric being revenue, the Y-metric being

profit, and the aggregatorbeing product category. That means the three product categories in the two

quadrants on the right make up more than 80% of the total revenue in the Southern New England and

Boston regions, and the rest of the 13 product categories on the left make up less than 20% of the total

revenue. The same thing can be said about profit; the aggregates in the top quadrants make up more than

80% of the profit, and the rest make up less than 20% of the profit.

16

Palm Trees

No. of Categories

Revenues

Gross Margin

Commission

Net Profit

Invoice Lines

Minnows

No. of Categories

Revenues

Gross Margin

Commission

Net Profit

Invoice Lines

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$ / Line

Amount % of Total % of Revenue

1

6%

$

38.00

12%

26,944.00

30.00

12%

80% $

21,659.00

7% $

2.00

1,886.00

11%

22.00

59% $

19%

15,780.00

707

Islands of Profit

No. of Categories

Revenues

Gross Margin

Commission

Net Profit

Invoice Lines

$ / Line

Coral Reefs

No. of Categories

Revenues

Gross Margin

Commission

Net Profit

Invoice Lines

Amount % of Total % of Revenue

12

75%

7%

15,308.00

56%

5%

8,513.00

8%

10%

1,467.00

12%

2%

1,795.00

$

$

$

$

4.00

2.00

0.40

0.50

3741

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

Amount % of Total % of Revenue

13%

2

62%

137,896.00

85%

65%

116,660.00

7%

55%

9,652.00

41%

70%

57,180.00

905

$ / Line

$

$

$

$

152.00

128.00

10.00

63.00

Amount % of Total % of Revenue

6%

1

$

19%

41,379.00

80% $

18%

33,310.00

11% $

26%

4,551.00

$ / Line

6,998.00

1036

9%

17%

39.00

32.00

4.00

$

6.00

Figure 1: Profit Map Overview Example'

This thesis utilizes Dr. Byrnes' naming convention for the four quadrants. The Islands of Profit

quadrant on the top right are high revenue and high profit aggregates; they are the bread and butter of the

business. The Minnows at the bottom left are low revenue and low profit; these smaller aggregates

sometimes may have strategic value beyond profit dollars, but sometimes may be a drag on the entire

business. The Coral Reefs at the bottom right are aggregates that are high revenue but low profit; this

usually means the aggregates here are not as efficient at earning net profit than their revenue suggests.

The Palm Trees at the top left, on the contrary, are aggregates who didn't make the top 80% revenue but

2

made the top 80% profit; they are the aggregates companies may overlook but want more of.

Each of the quadrants is summarized by a table of customizable metrics. The first column is a

number of metrics the user is interested in. The second column presents the sum of the corresponding

metrics in the quadrant. The third column represents how large each quadrant is as a percentage of the

total business. The fourth and fifth columns are ratios like gross margin, net margin, profit per invoice

line, etc.

2.3.2

Profit Levers

INumbers

2

in the figure are for illustrative purposes only.

Byrnes, Islands of Profit in a Sea of Red Ink.

17

Profit levers are "elements of a company's business model that can be adjusted to improve

profitability," in Dr. Byrnes' words. Prices, service level, lead time, and profit sharing are all examples of

profit levers a company can explore with each customer. This thesis will not go into specific profit levers

to be taken at Boston Scientific but will discuss the ways to explore profit levers in general.'

The optimal profit levers to pull are often very apparent from looking at the profit maps. For

example, a low gross-margin-to-inventory-dollar ratio is an indication that safety stocks are too high.

From there, the company can take a number of actions to reduce inventory: incentivize customers to order

fixed quantity at fixed intervals, pool terminal demands with multi-echelon network, or reduce shipping

time by changing the shipping method.4

2.3.3

Profitability Management Process

Profitability management is the last mile to the success of improving profitability, and arguably the

most difficult stage. In order to successfully manage profitability, top management needs to define its

strategy in terms of profitability and align its people, rewards, processes, and structure with that goal. Just

as andon/Kanban/jidouka are the tools that facilitate continuous improvements in Lean production, profit

map is a tool meant to elicit continuous improvements in profitability.5

3

Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

18

3

Profit Map

The construction of profit map is a two stage process.

3.1

Profitability Database

The first stage of modeling profit maps is to build a profitability database-a marriage between the

Profit & Loss statement and the invoices database. We begin with querying the invoice database for data

during the period of interest. These invoice lines are the atoms that make up the revenues and tell us

which sales rep sold how many of which product to which customer at what selling price on what day.

Expenses at the same atomic level are usually not always readily available, which is why we carefully

create assignment functions for each of the P&L elements. The P&L statement helps us identify the

biggest buckets of costs and reconcile unaccounted costs for one reason or another. Raw data from

different departments combined with assignment algorithms and assumptions (see Figure 2) tells us the

different buckets of costs at the most granular level-cost of goods sold by SKU, selling cost per PG,

R&D cost by product family, overhead per invoice line, and etc. Importantly, each element is assigned to

each invoice line through a well thought-out function reflecting the nature of the cost. We then augment

the invoice database with costs at the invoice level; now we can reconstruct a picture of the business'

finance from virtually any facet.6

6

Ibid.

19

L;Jk

Invoices

P&L

Algorithms &

Assumptions

Compensation

Structure

R&D Project Expense

Fulfillment Expense

Standard COGS

Accounts' Service

Demand

Profitability

Database

Cost

Allocation

Figure 2: Stage 1 - Build Profitability Database

3.1.1

Cost Assignment Philosophy

The key to a successful profit map is timeliness in profitability database construction, sometimes

at the expense of some accuracy. We must fight the urge to invest too much time and resources in

activity-based costing. A better approach is to iterate on the assumptions and algorithms in the future only

when the cost assignment will change the course of actions. Meanwhile, a 70% accurate profitability

database should already give us enough information on where to look for recommendations.7

It is equally important to not assign costs by revenue for the sake of convenience. Too often we

don't take the trouble to understand and investigate how resources are spent before defaulting to

spreading costs by revenue dollars. Let us take a little detour to illustrate this with the marketing expense

of McDonalds. At first glance it may be tempting to apply a percentage on the revenue as the marketing

expense incurred with the transaction, but we can do better. A reasonable approach is to find the invoices

that match the targeted customers, region, and promotional products of each campaign and spread the cost

of the campaign evenly over those transactions. Again, the idea is not to spend years calculating down to

the penny the amount of costs each invoice line bears, but for categories that are not insignificant to the

7

Ibid.

20

operations of the company, such as marketing to McDonalds, it is worth investing some thought into the

reasonable assumptions and algorithms of cost assignment.'

The categories of costs at the CRM Division are the cost of goods sold (COGS), selling cost,

service cost, research and development (R&D), period expense, distribution, and administration and

others. The COGS is made up of labor, material, scrap, and overhead; one would need to study the

operations and manufacturing process of each product to come up with a reasonable estimate. Selling cost

and service cost would be most accurately obtained from a time-tracking program, but since such a

program is not fully functioning at the point in time of the internship, we will interview the managers to

obtain an estimate. R&D and period expenses can easily be broken into projects, but tying the projects to

the products or product families requires interviewing the R&D Department. For the smaller remaining

buckets, I decided to spread them by revenue with the exception of distribution cost, which is spread by

invoice lines. In hind sight, spreading by invoice lines for administration and other costs is probably

better, as the number of invoice lines correlates directly with the complexity of the business.

It is not uncommon to have multiple iterations of discussions with the stakeholders on the

assumptions and algorithms used for assigning each bucket of cost. I conducted multiple discussions with

different departments within the CRM and Operations Division regarding whether the cost assignments

make intuitive sense and reflect the true cost of doing business before getting the key stakeholders to

agree with the model.

3.1.2

Scope for Data Gathering

We first decide on the time period and geography to gather the data on. We wish to choose a time

period recent enough to reflect the current state most accurately, but the time period needs to be long

enough to minimize the effects of random fluctuation in the data. The time period we choose to analyze is

the first nine months of 2013. As for geography, we wish to study the regions of Southern New England

8 Ibid.

21

and Boston due to the company's familiarity and proximity to the customers in those regions. However,

we do not have the breakdown of P&L statement at the regional level, so we decide to collect the invoices

for the entire US, then later zoom into the two regions for further analysis.

3.1.3

Invoices

The invoices are at the center of what makes up the profitability database. Each column in the

invoice table can become the aggregator when the user configures the profit map. So the more

information we gather at this level, the more configurations of profit map we can explore, the more

powerful the model. The downside is the model becomes more complex and cumbersome to process and

change. Table 1 lists all the columns in the invoice table.

Table 1: Invoice Columns

Column Name

Notes

Month

Customer Name

Name of the healthcare provider

A-

40

Jnzton." tIieeg.YfkAtqt4

GPO

Group purchasing organization's name (e.g. Premier)

Therapy

Which therapy the product is used in (e.g. Tachy, Tachy HF)

Invoice Document Number

Sales Rep Name

Sales Region Name

SaI1u Area N

Qua ntity

Lead Quantity

Note that some of the columns here can be implicitly calculated or looked up from other columns.

For example, quarter and month can be calculated from date; sales area and sales region can be looked up

22

from other tables with sales territory. We still choose to include these columns for convenience in the

profit map configuration stage.

3.1.4

Cost of Goods Sold

A good proxy for COGS is the standard cost and is accessible from SAP at Boston Scientific. The

standard cost of a product has four components: material, labor, scrap, and overhead. The standard

material and labor cost can be computed from materials consumed and total labor hours on the line; scrap

cost are wastages spread over the produced units; and overhead are building, utilities, and etc. spread

across the products and units. Generally speaking, the amount of overhead a product bears is a function of

the material, labor, scrap, capacity, utilization, footprint, forecasted volume, and other factors. Every year,

the Operations Division's Finance Department reviews those parameters, adds up the divisional overhead

for producing CRM products, and updates the overhead cost for each stock keeping unit (SKU). Table 2

shows a partial COGS look-up table with illustrative information.

9

Table 2: COGS Lookup Table

Material Number

Material Description Standard Costs

000000-002

Material 2

11.24

000000-004

Material 4

0.01

000000-006

Material 6

12.64

000000-008

Material 8

0.01

000000-010

Material 10

9367.67

000000-012

Material 12

9402.35

000000-014

Material 14

801.17

3.1.5

Selling Cost

9Numbers and names in the table are for illustrative purposes only.

23

Sales organization's expense is one of the largest expense category but hardest to assign at an

invoice level. To better assign selling cost to each invoice line, we interview and shadow a sales rep to

understand the sales organization and sales process.

Boston Scientific CRM Division's US domestic sales force are divided into 9 areas, each headed

by an Area Director (AD). Each area is sub-divided into a number of regions headed by Regional

Managers (RM). Each RM will typically have half a dozen Field Sales Reps (FSR) and half a dozen Field

Clinical Reps (FCR) responsible for the half-a-dozen territories in the region. Both FSRs and FCRs can

do regular patient checkup and participate in implant operations, but FSRs are usually the people making

the sale to the electrophysiologists or whoever is making the purchasing decisions. Consequently, FCRs'

compensation are largely base salary with a small component of regional performance, whereas FSRs

have on average half of their compensation based on their individual sales performance and the other half

base salary.

An FSR typically will have three types of activities on his calendar: cases, patient checkups, and

selling activities. Cases are the scheduled operations where Boston Scientific's products are used in the

procedures. The sales rep goes into the operating room (OR) with the products and the device

programmer to aid the physician for the entire duration of the surgical procedure. Procedures vary in

length depending on the therapy, but the majority takes less than an hour. Selling activities are meetings

with physicians with the objective of leading to a sale. FRSs and FCRs together spend roughly 50% of

their time on cases and selling. The remaining 50% of their time is spent on patient checkups, which

occurs for Boston Scientific patients every three months. Each checkup lasts around fifteen minutes, but

over the lifetime of the device or the patient, the number of checkups, and therefore the amount of hours,

FSRs/FCRs spend doing servicing activities can add up.

There are three types of selling costs going into a sale: commission, fixed selling, and service cost.

Commission is a percentage of the revenue depending on the therapy. The fixed selling is the time that

24

went into making the sale translated into dollar amount. And the service cost is the amount of service time

that will go into future patient checkups as a result of a particular sale. Commission is easy; we simply

multiply the revenue with the commission rate listed in the therapy column. We also assume that all sales

reps have the same commission plan, as that information is not disclosed to us. Fixed selling and service

costs, on the other hand, are quite tricky, as described in the next section.

0

Table 3: Regional Expensel

1000751-CRM

1000751-CRM

1000751-CRM

1000751-CRM

1000751-CRM

1000751 -CRM

1000751 -CRM

1000751 -CRM

1000751 -CRM

1000751 -CRM

1000751 -CRM

1000751-CRM

1000751 -CRM

1000751 -CRM

1000751-CRM

1000751 -CRM

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

Boston

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

1000754-CRM

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

New England

New England

New England

New England

New England

New England

New England

New England

New England

New England

New England

New England

New England

New England

FY3

FY13

Jan

F~b

M4ai

$2,808

$2,820

$3,133

Sal - Exempt/Salaried

$292

$215

$443

Employee Operating Expense

$1,348

$1,504

$1,354

Fringe Allocation

$0

$0

Bonus

$0

$2,898

$6,659

$3,569

Commissions

$160

$147

$149

Leased Vehicles - Adj

$0

Career Development - Adj

$0

$0

$0

$9

$0

Meetings

$372

$445

Travel and Business Meals - Adj

$375

$85

$20

HCP Expense - Adj

$28

$0

$0

$0

HCP Other (Actuals and R&E Grants)

$531

$672

$683

Samples + Inv Withdrawals - Adj

$0

$0

Info Systems

$0.

$44

$15

Supplies

$58.

$36

$11

$29

Other Discretionary

$23

$21

$30

IS Service Allocation

$0

$0

$0

$2,736

$3,134

$2,994

Sal - Exempt/Salaried

$549

$432

$358

Employee Operating Expense

$1,504

$1,437'

$1,313

Fringe Allocation

$885

Commissions

$2,453, $10,084

$117

$114

-$531

Leased Vehicles - Adj

$0

$42

Career Development - Adj

$0

$0

$0

$0

Meetings

$405i

$484

$380

Travel and Business Meals - Adj

$93

$89

$66

HCP Expense - Adj

$1,231

$1,112

$1,023

Samples + Inv Withdrawals - Adj

$0

$7

$0

Info Systems

$88

$15

$58

Supplies

$3

$42

Other Discretionary

$9

$26

$20

$32

IS Service Allocation

Table 3 shows the regions' expense by month with illustrative data. For simplicity's sake, we will

assume all categories of expenses besides commission and bonus are non-variable costs. Since the FSRs

10 Numbers and names in the table are for illustrative purposes only.

25

and FCRs spend on average half their time selling and half their time servicing, we boldly assign half of

each month's non-variable cost as fixed selling and the other half service costs. We also assume each of

the FSRs in the same region will bear an equal amount of fixed selling. Finally, we treat each sale of a

system, as approximated by the number of PGs sold, equally time-consuming. Now we have all the

information necessary to calculate the fixed selling cost for each invoice line. We illustrate this with an

example in Table 4. If Joe Smith is one of the five FSRs in region X who sold 10 systems this month, and

region X's non-variable expense this month is $100,000, then Joe will bear one-fifth of half of $100,000,

which is $10,000 in fixed selling, and each PGs he sold will bear one-tenth of that, which is $1,000 in

fixed selling. On the other hand, if Jane, one of 20 FSRs in region Y, sold four systems this month, and

region Y has a $20,000 non-variable regional expense this month, each PGs will bear only $125 in fixed

selling.

Table 4: Fixed Selling Cost Calculation Example"

FSR Name

Region

Non-variable regional expense

FSRs in same region

Systems sold

Fixed selling/PG

$

$

Joe

X

100,000 $

5

10

1,000 $

Jane

Y

20,000

20

4

125

Service cost per case is non-deterministic for various reasons. The remaining life of the

patient/device, where the patients perform the checkups, and the sales reps performing the checkups are

all unknowns ahead of time. Interviews with sales reps reveal that the biggest factor in determining the

service cost of each case is which hospital the case is performed at. The variation in service demand

serves as the primary factor in determining service cost at the invoice level. We have asked the regional

managers in the Southern New England and Boston regions to estimate the service time their teams spent

at each hospital using the most service-demanding hospital as a benchmark. We then normalize the

service demand to reflect the size of the share of service-cost-pie each hospital needs to take on.

"Numbers and names in the table are for illustrative purposes only.

26

Multiplying the total service cost incurred in the respective time period and region with the share of

service demand of each hospital gives us a dollar amount of service cost spent at the hospital. Finally,

dividing the number of PGs sold in the time period into the service cost yields the service cost per PG

sale. The argument against this assignment is assigning service burden generated by yesterday's sales to

devices we are selling today since the business is ongoing. The justification is servicing yesterday's sales

is effectively the cost of doing business today. In other words, if we stop all the servicing of devices sold

earlier, none of the sales would happen today. Though imperfect, this is the closest approximation we can

reasonably come up with given the information. Table 5 shows a partial table for service cost calculation

with illustrative numbers.

Table 5: Service Cost Calculation Example

Quarter

Region

Hospital

2

Service Demand Against Benchmark Service Demand Share

1 CRM S New England B

S New England

..

....

%

1 CRM

D

1 CRM S New England F

3.1.6

Service Cost

PGs Sold

Service Cost / PG

100%

14% $

10,000

49 $

204

5%

1% $

200

100

410

2 $

:$

25%

4% $

1,000

41 $

24

$4

1 CRM

S New England

H

20%

3% $

800

4 $

200

1 CRM

S New England

J

20%

3% $

800

43 $

19

1 CRM

S New England

L

20%

3% $

800

30 $

27

1 CRM

S New England

N

25%

4% $

100

2 $

50

Research & Development Cost

The R&D process has several attributes that make cost assignment difficult: distance from

production, long development cycle, and the magnitude of investment. Most of the R&D projects

underway at Boston Scientific are for products that will not come out in another year or two. In fact, most

of the R&D dollars are concentrated around only a handful of future products. Once the products being

developed go into full-fledged production, the sustaining R&D for it will drop rapidly and stay low for a

few years until the product's next generation is developed.

1

Numbers and names in the table are for illustrative purposes only.

27

There are several possible approaches to assigning each invoice line its R&D cost. Ideally if we

know the total R&D dollars spent over a product's lifecycle along with the product's historic and forecast

sales volumes, we can accurately determine the R&D spent per product per unit. That is unrealistic as we

don't have either number for most products. An alternative approach, which we did not take, is to only

assign R&D dollars spent on on-market products but keep track of off-market product R&D costs. In

other words, most invoice lines will have zero in R&D spending. One downside of this approach is that it

ignores most of the R&D spending costs that occurred in the time period, which is too significant to not

account for and will make the organization look more profitable than it really is. Another problem will

arise in the future; when future products go to market, they will have enormous R&D costs and will

appear uncompetitive against products for which we have zero R&D due to artificial reasons.

The approach we adopt is one similar to assigning service cost. If we think of the development of

the next generation of an existing product as what enables the company to stay in this competitive space,

we can justify assigning future product cost to current sales. We do so by attributing the development cost

of a product or platform to the closest product category it continues. Table 6 shows a partial list of

research projects, their purpose in terms of product category, and the amount of R&D spending in the past

three quarters. Some of the R&D projects are not product-family specific but can still account for a

significant amount of R&D spending, like quality. We sum up the R&D spending of all such projects and

attribute it to product-specific projects proportional to their R&D spending. Take the projects in Table 6

for example, if the R&D spending were $400, $300, $500, $200, and $100, respectively, the $500 from

Quality will be spread to the other projects, and the adjusted R&D spend will become $600, $450, $300,

and $150.

28

13

Table 6: R&D Projects' Product Category and Spending

Product Category R&D Spend R&D Spend Adjusted

25%

20%

Acc

25%

20%

Brady Lead

Project

PF Leads Delivery Systems

PF Atlas Lead Family

PF Quality

PF Cameron Device Family

PF Navigator Lead Family

20%.

25%

20%

Tachy PG

96%

4Flow

To assign each invoice line an R&D cost, we transform the information into an R&D cost per unit

look-up table, as illustrated in Table 7. The leftmost column indicates the aggregated units sold of all

products of the corresponding product category. The body of the table is a mapping of R&D projects to

project categories. The top row, units sold, tells us the sum of the units sold in all the product categories

related to the R&D project. For example, PF Leads Delivery Systems' Units Sold will be the sum of the

units sold of BRADY ACC, BRADY HF ACC, TACHY ACC, and TACHY HF ACC. With the adjusted

R&D spend, the units sold, and the mapping of projects to product categories, we can then arrive at the

R&D spend per unit by each product category. Using the invoice line's product category column, we can

look up the R&D cost attributable to each invoice line.

Table 7: R&D per Unit Calculation Example"'

Units Sold

Units Sold

R&D Spend Adjusted

Product Category\R&D Project

$

Project A

20

1,000.00 $

Project B

100 BRADY PG

200 BRADY HF PG

300

3,000.00 $

Project C

0

1

0

1

3.1.7

R&D/unit

1

-

tubf

620

620.00

$ 11.00

1$1100

A.

1$

Period Expense

Period expense is assigned the same way as R&D except where R&D has dozens of projects,

period expense has three big buckets. These projects and buckets will remain unnamed.

3.1.8

Distribution

Numbers and names in the table are for illustrative purposes only.

1 Numbers and names in the table are for illustrative purposes only.

13

29

Because the cost of losing a sale due to stock out is so high in this industry, Boston Scientific's

sales reps needs a way to ensure close-to-100% service level. The way the CRM Division achieves this

goal is to have a very short lead time from the DC to the sales rep. All orders from the sale are shipped

using FedEx Standard Overnight by default; around 10% of the orders are shipped with FedEx Priority

Overnight; and less than 5% of the orders are shipped with FedEx First Overnight.

The most practical way to assign distribution cost is to treat each unit's distribution cost the same,

regardless of revenue or product category. Though it is possible that some sales reps order FedEx First

Overnight more often than others, which is four times more expensive than FedEx Standard Overnight,

such situations are very rare and the amount of difference is insignificant.

3.1.9

Administration and Others

Administration and others include all other smaller slices of the P&L pie, including inventory re-

evaluation, marketing, inventory charges, variance, and royalties. Due to lack of proper data to assign

each category of cost more accurately, we resort to spreading them across invoice lines by revenue,

although an argument could be made for assigning these costs by transactions (invoice lines).

3.2

Profit Map Configuration

The frontend user interface allows users to configure the different profit maps they wish to explore.

How management can use this interface to uncover profit levers will be covered in the next chapter; we

first study what the tool is capable of. The parameters users can configure in the interface are: X-metric

and Y-metric, filter, aggregator, and metrics table. Once the user finishes configuring the setup and

proceeds to generate the profit map, the Excel macro will transform the profitability database based on the

profit map configuration and output a profit map sheet and four quadrant view sheets (see Figure 3).

30

* Profit Map Configuration

* X-Metric, Y-Metric

* Filter

* Aggregator

* Metrics Table

Profitability

Database

A

Profit Map

Generation

Profit Map

Palm Trees

Islands of Profit

Minnows

Coral Reefs

Figure 3: Stage 2 - Profit Map Configuration

3.2.1

X and Y Metrics

Profit maps typically segment the aggregates along the revenue dimension and the net profit

dimension, but we wish to allow for more versatility of the tool. One of profit map's primary functions is

to point out misalignment between a pseudo performance metric (e.g. revenue) and the real performance

metric (i.e. net profit), so giving the user control over which metrics to segment the aggregates would

enable the user to explore different kinds of metric misalignment. Figure 4 shows the control for

configuring X and Y metrics under "Step 1". Users can either select the metric from the dropdown or type

it in.

31

Step 1. Select X-Metric and Y-Metric

Step 4: Customize Metrics Table

Palm Trees

(Required)

Net Profit

Islands of Profit

(Denominator) (Denominator)

Minnows

IRpvpnus

Coral Reefs

(Required)

Revenue

Step 2. Select Aggregator/s

(Optional)

Revenue

Gross Margin

Commission

Net Profit

Quantity

+

Aggregator: Customer Name

Step 5: Hit the Button

Step 3. Select Filter and Filter Value

(Optional)

Filter on: GPO

Create Profit Map

(Optional)

Value = 'Novation

Figure 4: Profit Map Configuration User Interface

IOij;;ntitv

3.2.2

Aggregator/s

An aggregator is what the tool uses to cluster together the invoice lines. For example, when the

aggregator is "Customer Name," all invoices generated by that customer are grouped together, and we can

compare the revenues of different customers. In Figure 4, "Step 2" shows the control specifying

"Customer Name" as the aggregator. We also add in the option of allowing two aggregators to be joined

together to create more granular aggregates. For example, if we consider each hospital's different

therapies to be different business, we can join the customer name and therapy together. The resulting

profit map will treat, say, hospital A's tachy business metrics separately from hospital A's brady business.

3.2.3

Filter

We give users the control to zoom into a more specific area of the business. In Figure 4's "Step

3," by specifying "GPO" in the filter and "Novation" in the value field, the macro will only analyze

invoice lines whose GPO value is "Novation". Combined with the different aggregators, users can almost

explore an infinite number of profit map configurations. This set of capabilities enables various users to

explore the profitability of their respective business units.

3.2.4

Metrics Table

(Denominator) (Denominator)

uRevenue

No. of [A14ats

C

QuantiC

Figure 5: Metrics Table Template

JiSemi

Quanti

Figure 5 provides a close-up look at the metrics table, which is a template for how to display each

quadrant's metrics to the users. Starting at the top left cell in the table, the "Islands" cell will always

contain the name of the quadrant-Islands of Profit, Coral Reefs, Palm Trees, or Minnows-and that cell

cannot be changed. The "No. of [Aggregates]" cell is also not customizable. The macro will grab

aggregator information from the configuration and plug it in place of "[Aggregates]". The next five cells

are the customizable text fields reflecting the names of the metrics on their left. Users first pick the

metrics they wish to display in the "Amount" column using either the dropdown menu or text entry, then

modify the display names of those metrics on the right. The "Amount" column will display the number of

aggregates in the quadrant and the metrics formatted according to the symbol in each cell. A "#" will

instruct the macro to display the raw number; a "$" symbol tells the macro to display the content as dollar

amount; the "%" symbol formats the cell as percentage, and a blank cell means "do not display the

quantity". Next we have the "% of Total" column. It will always display each metric in the quadrant as a

percentage of all four quadrants' such metric combined. For example, if there are a total of 40 customers,

and four of them are the Island customers, then the % of Total cell will display 10%. The two columns on

the right are customizable ratios with the denominator metric selectable from the dropdown fields; the

headers are customizable as well, of course.

Users now can configure the profit map of interest and hit the "Create Profit Map" button and

begin analyzing the results.

3.3

Technical Challenges

Neither the backend database nor the frontend interface is without limitations by any means.

Updating the profitability database is anything but a push of a button; there is huge room for refining the

assignment algorithms for categories like R&D and period expense, and corner cases result in profit maps

that are uninformative. We now discuss some of these deficiencies in more detail.

3.3.1

Automated vs Manual Work

34

The process for creating the profitability database is a very manual-heavy work for several

reasons. First, sales and costs data come from multiple systems; secondly, cost assignment assumptions

and algorithms sometimes require interviewing the right stakeholders from different departments; lastly,

when numbers don't add up, we need to manually reconcile the differences and proactively look for error

in data.

Currently, data come from at least three separate sources. Invoice data come from a web interface

that outputs data in spreadsheets; R&D cost breakdown comes from a standalone tool; and COGS come

from the SAP client. There are technologies for integrating data from different sources such as Enterprise

Application Integration (EAI), Extract-Transform-Load (ETL), and other web services.

EAI, also known as Enterprise Information Integration, is a middleware that connects the

different applications and databases and provides a unified view of the organization's data. EAIs have the

advantage of providing instantaneous updates to the profit maps, which is a crucial in the success of

profitability management process, which we will discuss later in chapter 5. However, EAI solutions do

not come free; the time and money it takes to implement goes up quadratically with the number of

applications to be integrated. Fortunately, in this case, we only have three to four applications to integrate.

15 16 17 18 19 20

Another popular approach to data integration is the Extract-Transform-Load process. As its name

suggests, the process extracts data from outside sources, transform the data to fit operational needs, and

finally loads the data into a target database. Unlike EAI, ETL does not require a full-blown integration

between all applications; instead, the companies can selectively extract, transform, and load information

15

16

'?

18

Bernstein and Haas, "Information Integration in the Enterprise."

Gable, "Enterprise Application Integration."

Linthicum, EnterpriseApplication Integration/ David S. Linthicum.

Ruh, Maginnis, and Brown, Enterprise Application Integration[electronicResource].

19 Yongzhuang LiI and Chunfeng Yel, "The Research on the Integration Enterprises Application Architecture Based

on the Web Services."

20 "Avoiding Pitfalls of Integration Competency Centers."

35

as needed. This approach takes less time and resources to implement than EAI but is sufficient for the

purpose of generating profit maps.2'

22

23

There are also data that cannot be extracted from any application or database, such as cost

allocation assumptions and algorithms that can only be obtained from interviews. The service burden of

each hospital is a prime example. In the distant future, when the system keeps track of every sales rep's

time spent at each hospital and how researchers split their time between R&D projects, automatic cost

assignment may be possible, or experienced-based general cost functions could be developed. But for

now, manual assignment of costs is still the most convenient and preferred method.

Lastly, it is important to do a sanity check on whether the numbers make sense after pasting

numbers into formula. I worked with people from finance and sales operations to sample some of the

entries in the database just to see if any number is drastically out of line. Data is correct most of the time,

and we find explanations for what may seem like outliers. However, there are also occasions where

numbers don't add up due to missing data, in which case we must make educated guesses.

3.3.2

Moving Averages

We now revisit the R&D cost allocation with a focus on the sporadic nature of R&D spending. In

the CRM industry, we often see a huge spike of R&D investment in a product family for a few quarters

followed by a drought for an even longer period. For that reason, we choose to smooth out the R&D

spending with past quarters using moving average. Here we will discuss the difference between moving

average, exponential smoothing, and unsmoothed R&D costs. 24

21

Vance, ETL Extract, Transform, Load.

Qin Hanlin, Jin Xianzhen, and Zhang Xianrong, "Research on Extract, Transform and Load(ETL) in Land and

Resources Star Schema Data Warehouse."

23 Betancur-Caldero'n and Moreno-Cadavid, "A Multi-Agent Approach for the Extract-Transform-Load

Process

Support in Data Warehouses."

24 Ick Huhl, Viveros-Aguilera, and Balakrishnan, "Differential Smoothing in the Bivariate Exponentially

Weighted

Moving Average Chart."

22

36

As opposed to allocating the current-quarter spending to current-quarter sales, moving average

allocates an average of the past X quarters of spending to current-quarter sales for each product category,

where X is whatever management deems appropriate. One question that might surface is whether the

moving average R&D spending differs from the current-quarter R&D spending. If the discrepancy is

significant, the company can normalize the moving average R&D spending of each product category to

have them sum up to the current-quarter R&D spending. This approach still keeps the advantage of

smoothing out the bumps across product categories.

However, another concern that still remains is whether R&D spending from recent quarters are

more relevant than past quarters. One answer to this concern is to use the weighted moving average,

where the weight of the information decays linearly with age. One may also consider a more aggressive

technique, exponential moving average, or exponential smoothing, where the weight decays exponentially

with time. In this algorithm, the weight of the most recent period will account for a proportion, a, of the

entire average; the next most recent period will account for a * (1 - a) of the average; the

3 rd

most recent

period will account for a * (1 - a)2 of the average; and the last period will account for the remainder

portion. As illustrated in Table 8, if a is 50%, and the number of periods is four, then the weights of the

four periods will be 50%, 25%, 12.5%, and 12.5% respectively, and the weighted average of 2.125 is

biased towards the most recent period's cost, as designed.

Table 8: Exponential Smoothing Example

a= 50%

Most recent

2nd most recent

3rd most recent

14th most recent

1.5

50%

25%

2

12.50%

1

0

12.50%

Sum

3

0.5

0.125

0

2.125

We now compare the moving average, exponential smoothing, and unsmoothed R&D costs for

the product categories, as shown in Table 9. For confidentiality reason, the actual product category names

37

are disguised with letters. We also normalized the R&D cost per unit to compare against the moving

average data. We notice that the difference in R&D cost can vary up to three times between moving

average and unsmoothed data, while exponential smoothing data is somewhere in between. However, the

table does not reveal the fact that most of the product categories that have huge deviation from the

moving average are categories that have both lower volume and lower R&D spend to begin with. The

core product categories' R&D cost are relatively stable.

Table 9: Moving Average vs Exponential Smoothing vs Unsmoothed R&D Costs 25

PrdcCaegr

(Mvig

r

g

(Epoenia

Smohig

':1

smo

B

100%

118%

130%

E

D

100%

105%

109%

F

100%

211%

285%

H

100%

100%

100%

J

100%

211%

285%

L

100%

211%

285%

N

100%

105%

108%

P

100%

111%

119%

R

100%

100%

100%

Which smoothing technique is applied can influence the R&D cost by a lot in certain cases, but

the actual profit map landscape actually remains relatively unchanged. This is not surprising because the

changes in R&D costs apply to all accounts and all sales reps. Out of the three options, we pick moving

average because we believe it is most representative of the actual recent R&D spending behavior.

3.3.3

2

Returns

Product Category names are disguised with letters for confidentiality reasons.

38

A very difficult problem one encounters when building the profitability database is what to do

with returns. When a product is returned, the company has to refund the revenue, but does it make sense

to credit the costs of distribution?

One extreme is to credit all the costs-COGS, R&D, and even administration. The advantages of

this approach are simplicity and parity. The different categories of costs can be arrived at by multiplying

the quantity sold/returned (positive/negative) by the cost per unit from various lookup tables. More

importantly, a sale and return of the same quantity will cancel each other out, which makes sense if the

two transactions are purely transactional.

On the other hand, a sale and a return of the same product is more costly than doing nothing. The

material may not be reusable, so COGS cannot be refunded, nor is R&D cost refundable; the return of the

product actually costs the company more to bring it in than to ship it out; there is administration cost of

handling the return; there might also be negative implications in terms of customer relationships

associated with the return. To address those concerns, another way to handle return is to assign costs over

the absolute value of transactions. For example, a -$1 ,000 transaction has the same costs as a +$ 1,000

transaction.

26 27

We create two profit maps of the same type, each using one of the two aforementioned methods

of handling returns. The differences between the two profit map's landscapes are negligible and difficult

to detect. A closer examination reveals that returns account for less than 2% of the total transaction

dollars, and are well-spread among the accounts and products. This reaffirms the notion that a 70%accurate profitability database provides relatively informative picture, and that assignment functions

should only be deliberated and refined if they change the profit map landscapes significantly.

26

27

Bower and Maxham III, "Return Shipping Policies of Online Retailers."

Mukhopadhyay and Setaputra, "Return Policy in Product Reuse under Uncertainty."

39

4

Profit Levers

How can managers at Boston Scientific create concrete action plans from profit maps? Below we

share four of the more general observations. Due to the confidential nature of the results, sensitive names

and numbers are hidden.

4.1

Aggregate by Customer

We first investigate a basic profit map by aggregating the data by customer, as shown in Figure 6.

The customers are divided into the four quadrants. Right away we see the 80-20 rule at work here; more

than 80% of the revenue is contributed by 22 out of the 70 customers in the Southern New England and

Boston regions, and most of the net profits are attributable to less than 30% of customers.

Palm Trees

No. of Customers

Revenues

Gross Margin

Commission

Net Profit

Invoice Lines

Minnows

No. of Customers

Revenues

Gross Margin

Commission

Net Profit

Invoice Lines

$

$

$

$

Amount % of Total % of Revenue

0

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

$ / Line

Islands of Profit

No. of Customers

Margin

Gross

Revenues

Commission

Net Profit

Invoice Lines

0

Amount % of Total % of Revenue

48

69%;

18%

18%

20%

14%

$ / Linel

Coral Reefs

No.

of Customers

Revenues

Gross Margin

Commission

Net Profit

Invoice I ;nes

Amount % of Total % of Revenue

20

29%

$/ Line

76%

7

54

42

Amount %of Total %of Revenue

2,

3%:

$/Line

6

5

5%

4%

Figure 6: Profit Map by Customersn

Figure 7 is a magnified view of the Islands of Profit customers. The vertical y-axis represents the dollars

of revenue. Each column on the horizontal x-axis is represents the revenues and costs contributed by each

customer. The pink bar at the top is sum of net profit, and below it are the various cost elements, totaling

to the revenue from the customer. The customers are ordered from the highest net profit to the left down

28

For confidentiality reasons, some numbers are blacked out.

40

to the lowest net profit to the right. In this view, we see that among the profitable customers, there are still

customers who are generating profit more efficiently than others-customer C has much lower revenue

than customers D and E but trumps them in net profit.

41

Islands of Profit Customers

* Sum of Net Profit

* Sum of Royalties

* Sum of Variance

i Sum of Distribution

* Sum of Inventory Charges

41

C

" Sum of Marketing

U

0 Sum of Inventory Revaluation

* Sum of Admin

* Sum of Period Expense

i Sum of R&D

E Sum of Service Cost

" Sum of Fixed Selling Cost

" Sum of Commission

" Sum of COGS

I C

I

A

B

C

I

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

0

P

Q

R

S

Customer Names (Ranked by Net Profit)

2

Figure 7: Islands of Profit Customers View '

29

For confidentiality reasons, the y-axis scales have been removed, and customer names have been replaced by letters.

T

We now turn to the Minnows in Figure 8, where the majority of our customers lie. Same as

before, the vertical axis is revenue with the numbers removed for confidentiality reasons; however, the

scales of the two figures are different-even the highest revenue customer in the Minnows customers

view has lower revenue than the right-most customer in the Islands of Profit customer view. In addition,

this figure includes customers who contribute negative net profits. Here we notice two phenomenon:

customer M17 is an anomaly that stands out, and there are quite a few customers who generate positive

revenue but negative net profit. Customer M17 has an unusually low net margin, high COGS, and high

fixed selling cost. Those are signals that there are opportunities to improve in terms of sales efficiency

and/or product mix. More interestingly, there are a dozen or so customers to whom the CRM loses

money. We don't simply fire those customers. Instead, the sales force needs to first try to bring these