LJBRARIES

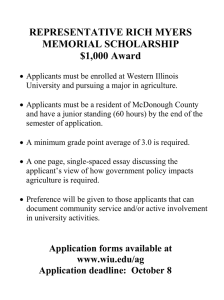

advertisement