D. Specific Heat of Below 1K CuPt.

advertisement

Specific Heat of Sr 3CuPt. 5 1r. 5 0 6 Below 1K

by

Adam D. Poleyn

A.B. Physics

Princeton University (1992)

Submitted to the Department of Physics

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

June 1999

© Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1999. All rights reserved.

Author ...........................

......................

Department of Physics

May 6, 1999

Certified by .......... /..-.-.

. 1 ....... . . . . . . . .....

Thomas J. Greytak

Professor of Physics

Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by......... . ...

Asso..

........

....

...

7...f...........

Thomas J. Greytak

Professor, Associate Dep rtment Head for Education

MASSACHUSETT$ NSTITUTE

LIBRARIE

! IES

Specific Heat of Sr 3CuPtO.Oro. 5 0 6 Below 1K

by

Adam D. Polcyn

Submitted to the Department of Physics

on May 6, 1999, in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Abstract

The alloy Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro.0 O6 was first fabricated by zur Loye and his collaborators at

MIT in 1994. Lee and his collaborators have modeled the material as a spin-' chain

with randomly distributed ferromagnetic (FM) and antiferromagnetic (AF) nearest

neighbor bonds of equal strength. Magnetization measurements indicate that the

material obeys the Curie Law to 4K, even though the AF and FM interactions have

strengths of order 30K. Lee's model explains this unusual Curie Law behavior, and

predicts that at temperatures well below 1K, the material should exhibit a scaling

behavior in specific heat and susceptibility characteristic of a new universality class

of disordered quantum spin systems, and contain an unusually large amount of spin

entropy. If a large amount of spin entropy is available in the material below 1K,

the material could be useful for magnetic refrigeration to temperatures as low as

100pK. Motivated by the work of zur Loye and Lee, I have constructed a new

apparatus to measure specific heat u of Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro.50 6 between 0.1K and 1K in

fields to 7T. I have developed thermal characterization techniques to verify that the

thermal properties of the calorimeter are appropriate for specific heat measurement

below 1K, and used the apparatus to measure specific heat of potassium ferricyanide

K 3 Fe(CN) 6 and Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1ro.5 0

6

using the AC and thermal relaxation methods. I

find no evidence for a phase transition to a long-range ordered state between 0.1K

and 2K in Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro.0 O 6 , and that u is consistent with the scaling law predicted

by Lee's model between 0.1K and 0.4K at zero field. Application of fields below 10kG

suppresses a, and at 10kG or obeys a T3/ 2 power law below 0.5K. I show that given

my data, Sr 3 CuPtO. 5 Iro. 5 0 6 is not superior to known paramagnetic salts for magnetic

refrigeration to lmK, and suggest that a successful understanding of the physics of

Sr 3 CuPtO.5 IrO. 5 0 6 below 1K may require consideration of interactions between spins

on different chains.

Thesis Supervisor: Thomas J. Greytak

Title: Professor of Physics

Acknowledgements

The work described in this thesis is a testimony to the love, support, and patience of

my wife, Amy Fronduti Polcyn. She has been a wonderful friend and helper to me

throughout my years as a graduate student, and I am grateful and honored to be her

husband.

I would also like to thank my advisor, Professor Thomas Greytak, for his support

and patience. The laboratory environment that he has created is an excellent one in

which to obtain an education in experimental physics, and I am honored to have been

his student and to have worked in this laboratory. Despite the inevitable frustrations

and setbacks, I have very much enjoyed working on this project and learning about

the physics of magnetic materials, and am grateful to him for proposing this project

for my thesis work.

I have been blessed with an excellent group of colleagues during my graduate

career. I have learned a great deal from each of them, and wish I had taken even

more advantage of the pool of talent that exists in this laboratory. Many of the

key ideas in this thesis resulted from conversations with them. In addition to their

talents as scientists, they are an excellent group of people, always ready to listen,

teach, help, and support. My classmate Dale Fried has been a great friend, brother,

and confidant to me. Tom Killian was an excellent office mate and colleague, and

probably took as many phone messages for me as I did for him. I have had many

enjoyable conversations with Lorenz Willmann. I am grateful to Stephen Moss for

his friendship and support, and for many enjoyable hours on the tennis court. It has

been a pleasure to work with David Landhuis, and I am grateful to him for taking

over as safety officer. In addition to these current members of the group, I would like

to acknowledge past members of the group, from whom I have learned most of what I

know: Mike Yoo, Claudio Cesar, Albert Yu, Jon Sandberg, and John Doyle. Finally,

I would like to acknowledge Professor Daniel Kleppner, with whom I worked early in

my graduate career. It was always a pleasure to talk with him about physics and to

listen to his stories.

I have also had the pleasure of supervising several undergraduate projects during

my graduate career. It was a pleasure to supervise Carlo Mattoni's thesis, and a lot

of fun to work with him. I have also enjoyed working with Mihai Ibanescu, who I in

many ways consider more of a colleague than a student.

Paul Jackson has been an excellent friend and brother to me over the latter half of

my years at MIT. His constant support, prayers, and concern have been a great source

of encouragement to me, as have the many joyful times we have shared together.

There are many other people who have made my years at MIT more enjoyable,

and supported me along the way. Among them, I would like to mention Bryan Atchison, Jeff Niemann, Scott Socolofsky, members of the Eastgate Graduate Christian

Fellowship Bible Study, and members of my St. Ignatius small group, especially Ed

and Mary Dailey.

I would also like to acknowledge the love and support of other members of my

family, especially my parents, Dr. Daniel Polcyn and Elizabeth Polcyn. They have

been a constant source of encouragement, comfort, and support. I am grateful to my

son, Stephen, who always smiled for me when I came home after a long day at the

lab and has brought both Amy and me so much joy. I would also like to acknowledge

the support and love of Anne and Bob Fronduti, John and Meghan Fronduti, Karen

Fronduti, and Sarah Polcyn.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge and thank my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.

He is the one who has put all these people in my life, Who has given me the opportunity to study physics, and Who has created the amazing things I have had the

pleasure to study as a graduate student.

Psalm 116

I love the Lord, because He hears

My voice and my supplications.

Because He has inclined His ear to me,

Therefore I shall call upon Him as long as I live.

The cords of death encompassed me,

And the terrors of Sheol came upon me;

I found distress and sorrow.

Then I called upon the name of the Lord:

"0 Lord, I beseech Thee, save my life!"

Gracious is the Lord, and righteous;

Yes, our God is compassionate.

The Lord preserves the simple;

I was brought low, and He saved me.

Return to your rest, 0 my soul,

For the Lord has dealt bountifully with you.

For Thou hast rescued my soul from death,

My eyes from tears,

My feet from stumbling.

I shall walk before the Lord

In the land of the living.

I believed when I said,

"I am greatly afflicted."

I said in my alarm,

"All men are liars."

What shall I render to the Lord

For all His benefits toward me?

I shall lift up the cup of salvation,

And call upon the name of the Lord,

Oh may it be in the presence of all His people.

Precious in the sight of the Lord

Is the death of His godly ones.

O Lord, surely I am Thy servant,

I am Thy servant, the son of Thy handmaid,

Thou hast loosed my bonds.

To Thee I shall offer a sacrifice of thanksgiving,

And call upon the name of the Lord.

I shall pay my vows to the Lord,

Oh may it be in the presence of all His people,

In the courts of the Lord's house,

In the midst of you, 0 Jerusalem.

Praise the Lord!

For Amy

Contents

1

Introduction

1.1 Properties of Spin Chains

1.2

1.3

2

3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

23

Sr 3 CuPt1pIrpO6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Specific Heat of Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1ro. 5 0 6 below 1K . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

32

26

Random Quantum Spin Chains and Sr 3 CuPt 1 _pIrpO 6

35

2.1

Theoretical Work on RQSC

2.2

Experimental Work on Sr 3 CuPt1pIrpO 6

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

43

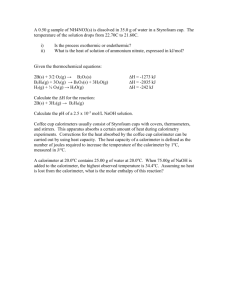

Methods

3.1 Quasi-Adiabatic Calorimetry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.2 Thermal Relaxation Calorimetry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.3 AC Calorim etry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

51

51

52

54

4 Apparatus

4.1 Dilution Refrigerator and Magnet

4.2 Heat Capacity Experiment . . . .

4.2.1 Support Structure . . . . .

4.2.2 Calorim eter . . . . . . . .

4.2.3 Calorimeter Models . . . .

4.2.4 Thermometry . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

59

59

59

59

63

64

67

5 Potassium Ferricyanide Experiment

5.1 Calorimeter Preparation . . . . . . . . .

5.2 AC Method Procedures . . . . . . . . . .

5.3 Thermal Relaxation Method Procedures

5.4 Empty Calorimeter Results . . . . . . .

5.5 K 3Fe(CN) 6 Calorimeter Results . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

69

69

71

74

77

79

.

.

.

.

.

87

87

88

88

93

93

6

Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro. 5 0 6 Experiment

6.1 Calorimeter Preparation . .

6.2 AC Method Procedures . . .

6.3 Thermal Relaxation Method

6.4 Empty Calorimeter Results

6.4.1 AC Method Results .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

Procedures

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

11

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

6.5

6.6

7

6.4.2 Relaxation Method Results .

Sr 3CuPtO.5 IrO. 5 0 6 Calorimeter Results

6.5.1 AC Method Results . . . . . .

6.5.2 Relaxation Method Results .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

96

103

103

107

111

Sr 3 CuPtO.5 IrO. 5 0 6 Specific Heat Determination

Conclusions and Future Work

7.1

Sr 3 CuPtO.5 IrO. 5 0 6 Specific Heat Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7.2

7.3

7.4

7.5

Discussion

Discussion

Discussion

Discussion

7.6

7.7

I: Entropy, Field Dependence . . . . . . . . . .

II: Comparison with RQSC Theory . . . . . . .

III: Comparison with Beauchamp Results . . .

IV: Miscellaneous Interpretations . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Prospects for Adiabatic Demagnetization of Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro. 5 0 6 .

Future W ork . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

113

113

116

119

120

121

122

124

A Calorimeter Conductance from Power/Temperature Curves

127

B Exponential Fits with Instrumental Response

133

C Schwall Model

135

D Model for AC Transfer Function in Presence of - 2 Effect

139

Bibliography

143

12

List of Figures

1-1

1-2

1-3

1-4

1-5

Ordered Ising chain at T = 0 (top) and Ising chain with fluctuation

(bottom ). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ordered Ising net at T = 0 (left) and Ising net with fluctuation (right).

Specific heat of various types of spin chains. The AF and FM chain

results were taken from [5], extrapolated to zero temperature using

simple spin wave theory, and the classical result from [4]. These results

are plotted assuming the Furusaki Hamiltonian (1.2); the Bonner and

Fisher Hamiltonian uses 2J rather than J. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Representation of T = 0 FM spin wave. Rather than reducing the

chain magnetization by breaking the chain at a single point, which

costs energy 2J, the magnetization is reduced in a spin wave by tilting

all spins slightly off the z axis, which costs much less energy. The spin

wave is a traveling wave in which the difference in azimuthal angle

between adjacent spin sites in the wave is constant. . . . . . . . . . .

Crystal structure of Sr 3 MM'0

6

22

22

24

25

. Left: view along the length of a chain,

showing alternating MO 6 trigonal prisms (M represented by the small

ball at center of prism) and M'O 6 octahedra (M' represented by the

large ball at center of octahedron). Right: view down the c axis.

Clusters of 3 Sr ions surround each chain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

27

M/H data for (top left) Sr 3 CuPtO6 , (top right) Sr 3 CuIrO6 , and

Sr 3 CuPt0 .5 Ir 0 .5 0 6 (bottom). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

29

1-7

1/x data for Sr 3 CuPtI_,IrO

. . . . . . . . .

30

1-8

1/X theoretical prediction of Lee and collaborators [17]. . . . . . . . .

31

2-1

Schematic view of spin wave confinement. Due to different dispersion

relations for FM and AF segments, spin waves from a given segment

do not propagate into adjacent segments. A mechanical analogy is a

rope with discontinous changes in thickness. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Missing entropy as a function of p, calculated with (line) Equation 2.10

and (open circles) HTE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Spin chain considered by Westerberg et al. (Equation 2.17). The

FM segments form large effective spins, separated by AF segments of

variable length. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1-6

2-2

2-3

6

taken by Nguyen [15].

13

36

38

39

2-4

Schematic of the RSRG method. A renormalization step proceeds by

first identifying Ao, the strongest bond in the chain. Then the two

spins linked by Ao are frozen to form an effective spin SL + SR, and

the nearest neighbor bonds renormalized to A1 and A 2 . As the chain

Ao, it effectively carries out a step in the RSRG. .

40

M versus H data of Beauchamp and Rosenbaum on p = 0.5, 0.667

sam ples. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

45

. . . . . . . .

46

cools below kBT

2-5

-

2-6

AC susceptibility data of Beauchamp and Rosenbaum.

2-7

Recent AC susceptibility data on Sr 3 CuPt. 5 Iro.5O 6 taken by Beauchamp. 47

2-8

Magnetization versus field for Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1r o.5 0 6 samples used in this

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

48

Heat capacity data of Ramirez. In each case, the sample consisted of

0.2g of the Sr 3 MM'0 6 material, and 0.2g of silver powder, which were

compressed together to form a pellet. The pellet was then glued to the

calorim eter [32]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

49

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

53

thesis.

2-9

3-1

Thermal circuit for Schwall model.

3-2

Thermal circuit for Sullivan and Siedel model. The calorimeter and

sample are assumed to be in excellent thermal contact, so that the

slab with heat capacity Ct0, represents the entire sample/calorimeter

assembly. Heat flux = -e"t (a is slab cross-sectional area) is applied

at one end of the calorimeter by the heater, and temperature T =

Td, + Tac is sensed at the other side of the calorimeter. Heat is dumped

to thermal ground (the heat bath) through the weak link conductance

K . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . .

4-1

4-2

4-3

4-4

Overall view of apparatus. Only one calorimeter stage is shown. Note

that devices (heater, thermometer) are not shown on the calorimeter.

.

54

61

Wireframe view of calorimeter stage. The calorimeter sandwich (sample dough between two quartz plates) is supported by vertical and

horizontal vespel pegs. These pegs are glued into brass L brackets. . .

62

Top view of one calorimeter plate, showing configuration of heater,

thermometer, and thermal link. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

62

Expected heat capacity of various calorimeter components. The N

grease data below 0.4 K was obtained by linear extrapolation, which

is reasonable for glassy materials [47]. The quartz data below 0.3 K is

a T 3 extrapolation, which underestimates the true heat capacity [47].

Also shown are expected empty calorimeter heat capacity and measured empty calorimeter heat capacity from Sr 3 CuPt. 5 Iro. 5O 6 experiment, and Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1r o .5 0 6 heat capacity measured here (below 1K)

and by Ramirez [15](above 1K). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

65

4-5

Expected thermal conductance of various calorimeter components. The

PtW entry is for 16 1 mil diameter PtW wires, each 12 inch long (representing the heater and thermometer lead wires). The NbTi entry is

for the same number and lengths of 5 mil diameter NbTiwires. The

quartz/sample boundary resistance is taken to be the same as that

between copper and glue. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

66

5-1

Monoclinic unit cell of K3 Fe(CN) 6 . Closed spheres represent Fe, open

spheres K, open diamonds C, and closed squares N. 3, the angle between a and c, is approximately 107', and a = 7.04A, b = 10.44A,

and c = 8.4A. Six cyanide groups surround each Fe, in approximately

octahedral coordination. Here, only two Fe ions are shown with all

cyanide groups. The closest cyanide groups on nearest neighbor sites

are 2.74A apart on the chain axis a. For nearest neighbors along b, the

closest cyanide groups are 6.14A apart. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

70

5-2

Apparatus used to measure AC heat capacity for Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro. 5 0 6 and

5-13

K3 Fe(CN) 6 experiment. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

LR-400 bridge transfer function measured with JFET . . . . . . . . .

Effect of LR-400 transfer function on empty calorimeter 102 mK thermal transfer function. The transfer function is normalized for power.

Typical power/temperature curve for K3 Fe(CN) 6 calorimeter, without

baseline drift correction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Typical power/temperature curve for K3 Fe(CN) 6 calorimeter, with

baseline drift correction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Empty calorimeter thermal transfer functions, measured and as calculated using the two-wire model and published data on calorimeter

m aterials. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Upper limit on AC empty calorimeter heat capacity. . . . . . . . . . .

K3 Fe(CN) 6 calorimeter 108 mK thermal transfer function, with fit to

two-wire model and resulting SSGI transfer function. . . . . . . . . .

K3 Fe(CN) 6 calorimeter 140 mK thermal transfer function, with fit to

two-wire model and resulting SSGI transfer function. . . . . . . . . .

K3 Fe(CN) 6 calorimeter 303 mK thermal transfer function, with fit to

two-wire model and resulting SSGI transfer function. . . . . . . . . .

K3 Fe(CN) 6 calorimeter zero field AC and relaxation heat capacities,

with data for K3 Fe(CN) 6 single crystals published by Fritz. . . . . . .

K3 Fe(CN) 6 calorimeter field-dependent AC heat capacity. . . . . . . .

6-1

Typical power/temperature curve for the Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1ro. 5 0 6 experi-

5-3

5-4

5-5

5-6

5-7

5-8

5-9

5-10

5-11

5-12

6-2

6-3

6-4

ment, with drift correction.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Apparatus used to measure relaxation heat capacity

Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1ro.5 0 6 experiment. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Raw AT(t) (bottom curve) and AT(t) after averaging ten decays

curve). Top curve is shifted up by 2 mK for comparison. . . . .

Empty calorimeter 128 mK thermal transfer functions. . . . . .

15

. . .

for

. . .

(top

. . .

. . .

72

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

80

81

83

84

90

91

92

93

94

Empty calorimeter 400 mK thermal transfer functions. . . . . . . . .

and

correction,

Empty calorimeter AC heat capacity with off-plateau

96

relaxation heat capacity. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6-7 Empty calorimeter AC (no off-plateau correction) and relaxation heat

97

capacity, 0 kG and 1 kG. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

heat

relaxation

correction)

and

off-plateau

AC

(no

6-8 Empty calorimeter

capacity, 3 kG and 5 kG. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

6-9 Empty calorimeter low temperature AT(t), showing best fit to sum of

99

two exponentials. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

meato

bath

Kb,

conductance

zero

field

thermal

calorimeter

6-10 Empty

sured and predicted from published data on copper. . . . . . . . . . . 99

6-11 Field dependence of Kb. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

6-5

6-6

6-12 Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro.50 6 calorimeter 136 mK thermal transfer functions. .

6-13 Sr 3 CuPtO. 5 1r o .5 0 6 calorimeter 400 mK thermal transfer functions. .

6-14 Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro. 5 0 6 calorimeter AC heat capacity with off-plateau cor-

103

104

rection, and relaxation heat capacity data. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

6-15 Sr 3 CuPtO. 5 1ro. 5 0 6 calorimeter AC (no off-plateau correction) and re-

laxation heat capacity, 0 kG and 1 kG. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

6-16 Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1rO. 5 0 6 calorimeter AC (no off-plateau correction) and re-

laxation heat capacity, 3 kG and 5 kG. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

6-17 Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1ro. 5 0 6 calorimeter AC heat capacity data above 1 K. . . . 108

6-18 Excess Sr 3 CuPtO.s

5 ro.0 O 6 calorimeter AC heat capacity data above 1 K

(see text). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

6-19 Sr 3 CuPtO.5 I r o . 6 calorimeter zero field thermal conductance to bath

Kb, measured and predicted from published data on copper. . . . . . 110

6-20 Field dependence of Kb, Sr 3CuPtO.5 1ro. 5 0 6 calorimeter. . . . . . . . . 110

111

6-21 High field heat capacity of Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro. 5 0 6 and empty calorimeters.

7-1

7-2

7-3

Zero field u/T for Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1r o .5 0 6 , fit below 0.4K. . . . . . . . . . . 114

Zero field u/T for Sr 3 CuPtO. 5 1r o .5 0 6 , fit to all data. . . . . . . . . . . 114

7-5

7-6

6. .

Zero field specific heat for Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro.5

0

Low field u/T for Sr 3 CuPtO.5 IrO.5 O6 . . . . . . .

o at 10kG for Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro. 5 0 6 , and fit to a =

Specific Heat of Sr 3 CuPtO.5 IrO. 5 0 6 as a function

7-7

Comparison

7-4

of various

paramagnetic

salt

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

115

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

AT3/ 2 + B. . . . . . .

of field at 130 mK. .

115

specific

116

117

heats with

Sr 3 CuPtO.s5 r o.5 O 6 . The dotted line is an extrapolation of the power

law predicted by theory for CPI in the universal regime.

. . . . . . .

123

A-i Thermal circuit for case 1. Temperature Tt is measured with the

bottom calorimeter thermometer, referenced to the bath temperature.

Power Qt0, is applied to top heater or Qbot is applied to bottom heater. 128

A-2 Thermal circuit for case 2. Temperatures is measured with the bottom

(Tt) or top (Tt0p) calorimeter thermometers, referenced to the bath

temperature. Power Q is applied with the bottom heater. . . . . . . . 130

16

C-1 Thermal circuit for two-link Schwall model. All temperatures are referenced to the bath temperature, and T2 (t) is measured. . . . . . . .

136

D-1 Thermal circuit for calculation of Schwall model transfer function. The

heater applies flux q at position 0. The thermometer is located at

position m . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

140

17

18

List of Tables

5.1

5.2

6.1

6.2

6.3

K3 Fe(CN) 6 calorimeter K, estimates. K, was determined from a fit of

the transfer function to the two-wire model (2WTF Fit), and a lower

limit on K, was determined by comparison of the data and calculated

two-wire transfer functions with various K. (TF Low. Lim.). . . . . .

Heat capacity data taken with relaxation method. Note that the

empty calorimeter results ("Empty Cal. C") are an upper limit due

to the low LR-400 bandwidth, and are for 68 mg of N grease. The

K3 Fe(CN) 6 calorimeter results ("K 3 Fe(CN) 6 Cal. C") are for 6.44 mg

K3 Fe(CN) 6 and 13.7 mg N grease. The "Fritz C" column is the heat

capacity of 6.44 mg of K3 Fe(CN) 6 from the Fritz paper. See text for

explanation of the "errors" in the Fritz data. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

82

85

Estimates of empty calorimeter K.. K, was determined from a fit of

the transfer function to the two-wire model (2WTF Fit), and from

the slopes of the power/temperature curves and Equation (6.1) (PT

Slope). Lower limits on K, were determined by comparison of the

data and two-wire transfer functions with various K, (TF Low. Lim.),

and by varying the power/temperature curve slopes appropriately by

one standard deviation (PT Low. Lim.). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

Relaxation heat capacity from various thermometer/heater combinations on the empty calorimeter. The notation Cth refers to heat capacity measured with thermometer t, heater h . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

Parameters for Schwall model of empty calorimeter. The values with

an "x" next to them are from fits of the measured AC transfer function to the Schwall model. The Cu Fing. column shows estimated

heat capacity for two sets of copper fingers. The Vespel column shows

estimated heat capacity and conductance for the Vespel pegs. . . . . 102

6.4

Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1ro.5 0 6 calorimeter K,.

6.5

the transfer function to the two-wire model (2WTF Fit), and from

the slopes of the power/temperature curves and Equation (6.1) (PT

Slope). Lower limits on K, were determined by comparison of the

data and two-wire transfer functions with various KS (TF Low. Lim.),

and by varying the power/temperature curve slopes appropriately by

one standard deviation (PT Low. Lim.). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

Parameters for Schwall model of Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro.5 0 6 calorimeter. . . . . 109

19

K, was determined from a fit of

6.6

Relaxation heat capacity from various thermometer/heater combinations on the Sr 3 CuPtO.5 Iro.50 6 calorimeter. The notation Cth refers to

heat capacity measured with thermometer t, heater h. . . . . . . . . . 109

20

Chapter 1

Introduction

One-dimensional spin systems ("spin chains") have been a subject of interest in condensed matter physics and statistical mechanics for many decades. Originally, such

systems were of interest because theoretical problems in many-body physics, phase

transitions, and critical phenomena were more tractable in one dimension than in

three; hence, it was hoped that a greater understanding of critical phenomena in

our three-dimensional world could be obtained by solving the corresponding onedimensional problem [1],[2]. In the late 1960's and early 1970's., powerful theoretical

methods such as the Renormalization Group were developed and applied to these

many-body one-dimensional problems. It quickly became clear that the hope of "extrapolating" one-dimensional results to three-dimensional systems would not be realized, as the behavior of spin chains exhibited profound qualitative differences from

that of three-dimensional systems. Around the same time, three-dimensional materials whose behavior approximated that of the one-dimensional systems were discovered

in the laboratory, and the study of one-dimensional spin systems became a subject

of interest in its own right. This study continues today, and has been characterized

by a remarkable interplay between theory and experiment, due to the ability of theorists to solve many one-dimensional problems on the one hand, and the ability of

experimenters to produce materials to which these theories apply on the other.

Why do one-dimensional spin systems differ from three-dimensional? Consider

two spin systems, one one-dimensional and the other three-dimensional, in which

nearest-neighbor spins interact with a coupling of strength J. This coupling could

be produced by (for example) direct exchange, superexchange, or dipole interactions.

For temperatures kBT > J, the interaction between the spins is unimportant; in

this temperature range, the systems will behave identically. They will have zero

magnetic heat capacity (in zero field), and their susceptibility X will obey the Curie

Law x = c/T. At thermal energies kBT ~ J the systems will behave quite differently.

The primary factor that distinguishes their behavior is the relative importance of

thermal fluctuations of the spin degree of freedom. Consider a hypothetical Ising

chain (that is, one in which the spin can have only two values, up or down) in which

all spins are aligned (Figure 1-1). If a fluctuation occurs at a single site, the chain is

split into two sections, one in which all spins are up, the other in which all are down.

The energy cost of such a fluctuation is 2J, where J is the coupling between nearest

21

I\ lIT1 II

ll II

Figure 1-1: Ordered Ising chain at T = 0 (top) and Ising chain with fluctuation

(bottom).

neighbor spins. However, since the fluctuation can occur at any of the N sites in the

chain, the entropy gain is k, In N. Hence the free energy change for this fluctuation

is

(1.1)

AF = 2J - kBT inN

For the ordered state to be stable, AF > 0, that is N < e 2 J/kBT. For a macroscopic

sample, this condition is likely not to hold. Hence it is .easy" to introduce thermal

fluctuations into the chain and destroy the order [3].

Figure 1-2: Ordered Ising net at T = 0 (left) and Ising net with fluctuation (right).

The same is not true in higher dimensions. For example consider a two-dimensional net of aligned Ising spins (Figure 1-2) with a fluctuation analogous to the

one-dimensional case. Here, the energy cost is 2Jv/N, and the entropy gain kB In A.

The stability condition is then N < e4J /kBT, which holds for large N. Hence we

see that it is more difficult to destroy the order in higher dimensions.

In fact, due to these fluctuation effects, a one-dimensional system will not exhibit

22

long-range order down to T = 0. On the other hand, short range order does develop

in the chain as it is cooled below kBT - J, and the entropy of the system is gradually

reduced over a wide temperature range through this short-range ordering. Hence the

correlation length (T), that is the length in the chain over which this short-range

order is maintained, is a quantity of great interest in the theory of one-dimensional

spin systems, and increases slowly as temperature is reduced.

Within one dimension, there are other properties of the chain that are important

for determining its behavior. One is the nature of the interaction J between the spins;

in particular, whether it is ferromagnetic (FM) or antiferromagnetic (AF), whether it

depends on the spin directions, and whether it involves only nearest neighbor spins. If

the interaction depends on spin direction, we may have Ising (if J2, Jy = 0, J, # 0),

XY (if J1 = Jy :L 0, JZ = 0), or Heisenberg (if Jx = Jy = J, = 0) spins, all of which

show different behavior. Another important property is the magnitude of the spin.

For example, a spin-J chain behaves quite differently from a spin- chain. In the next

section, I will consider effects of the spin magnitude in particular. This will highlight

the differences between quantum spin chains (with spin near 1) and the more intuitive

classical chains (with S - oc) that are important for an understanding of this work.

1.1

Properties of Spin Chains

Because the theory of Sr 3 CuPtjpIrpO6 assumes a nearest-neighbor Heisenberg de-

scription for the spin interactions, I will also assume that for the chains I describe

below. In the Heisenberg model, the interaction between nearest-neighbor spins is

isotropic. The Hamiltonian is written

L-1

H = JZ

L-1

Si -Sii - pHz E Si

i=O

(1.2)

i=O

where the sum is taken over all sites in a chain of length L (that is, having L sites;

length will always be measured in units of the lattice constant), and the Si are in

general quantum spin operators. For J < 0, we have a Heisenberg ferromagnet; for

J > 0, an antiferromagnet. For simplicity, I will take H, = 0. I will also focus

primarily on the entropy and specific heat. (In this thesis, specific heat is taken to

be n! dT'I, with units J/mol/K, and heat capacity Q/dT, with units of J/K.)

I begin with the classical spin chain. In this case, the spin Si is treated as a classical

vector. While this may seem like an unphysical idealization (real spins are quantum),

the classical approximation already works quite well for spin- at temperatures not

too close to T = 0 [2]. However, it is considered here because it follows intuition

most closely, and so will help to highlight the non-intuitive properties of the quantum

chains. In order to obtain a classical vector from the quantum operator Si, one has

the sense that the limit S -+ oc should be taken, as this will lead to an infinite number

of possible Sz, Sy, S,, as is the case for a classical vector. In order to take this limit,

define the unit operators si = Si/S [4], and note that the commutation relations for

23

these unit operators are, for example,

ss

-

ss =

(1/S)is

(1.3)

Also, set JS2 = Jc; then the Hamiltonian (1.2) becomes

L-1

(1.4)

H = Jc E Si *si+1

i=o

Given the commutation relations (1.3), in the classical limit S -+ oo all spin operators

commute. Hence for the FM case, the ground state (attained only at T = 0) will have

all spins pointing in the same direction, and in the AF case nearest neighbor spins will

point in opposite directions. Excited states can be formed by changing the relative

orientations of nearest neighbors by an infinitesimal amount (in this sense, the T = 0

long-range order for the classical chain is even less stable than that of a quantum FM

chain; i.e., the energy cost of excitation is infinitesimally small, whereas the entropy

gain is still k, ln N). The classical nature of the spin leads to unphysical results for

the entropy and heat capacity; at infinite temperature, the entropy is expected to be

infinite; also, Fisher found for the specific heat [4] (Figure 1-3)

1.0

-Classical

o FM

* AF

0.8

0.6

0.4

-

-

0

-

0.2

00

00

0

0

0

0

CO

K

0

I

0.2

0.4

I

I

0.6

0.8

1.0

kT/J

Figure 1-3: Specific heat of various types of spin chains. The AF and FM chain results

were taken from [5], extrapolated to zero temperature using simple spin wave theory,

and the classical result from [4]. These results are plotted assuming the Furusaki

Hamiltonian (1.2); the Bonner and Fisher Hamiltonian uses 2J rather than J.

24

2

c =1c =- 1 ( 2k,

2 TBsinh

T ~

J

h2

(15

1.3

c(T) does not approach zero for T -+ 0, so the entropy S(T) = f6 c(T')/T'dT'

approaches minus infinity as T -+ 0. Hence near zero temperature, the classical

approximation will not describe any real system and an appropriate treatment will

have to consider the spins to be quantum in some way. Another important observation

about the entropy and specific heat in the classical chain is that they are the same

for both the FM and AF chains.

I turn now to the FM spin-} chain. In this case the Si do not commute, and it is

not immediately clear that the classical ground state, with all spins pointing in the

same direction, will also be the spin-! chain ground state. However, a straightforward

analysis [6] shows that the ground state is indeed the same as in the classical case,

and that the lowest-lying excited states at T = 0 can be described by introducing spin

waves into the chain. A spin wave, or magnon, reduces the total chain magnetization

by one unit, and is a traveling wave with dispersion hw = 4SJ(1-cos ka). A schematic

representation of a FM spin wave is shown in Figure 1-4. For temperatures above

T = 0, spin waves are still expected, although the approximation S_ ~ S on which

the T = 0 analysis relies no longer holds [7]. Also, the absence of order in the id chain

at finite temperature changes the spin wave spectrum. In particular, spin waves with

wave vector k less than the correlation length ((T) will exhibit overdamped behavior,

whereas spin waves with larger k will continue to exhibit oscillatory, traveling wave

behavior [2]. These facts, along with the observation that spin waves do not obey the

superposition principle [6], make it seem unlikely that it will be possible to compute

the specific heat using a Debye-like model with the small wave-vector approximation

w = 2SJk 2 of the dispersion for the T = 0 spin wave. The Debye-like model predicts

c oc v/Y; detailed numerical calculations by Bonner and Fisher [8] confirm that the

specific heat has this temperature dependence at the lowest temperatures, although

the amplitude of the v'T term is a factor of 1.3 smaller than is predicted by spin-wave

theory. The Bonner and Fisher result is plotted in Figure 1-3.

T7TT7TVT

Figure 1-4: Representation of T = 0 FM spin wave. Rather than reducing the

chain magnetization by breaking the chain at a single point, which costs energy 2J,

the magnetization is reduced in a spin wave by tilting all spins slightly off the z

axis, which costs much less energy. The spin wave is a traveling wave in which the

difference in azimuthal angle between adjacent spin sites in the wave is constant.

25

For the AF spin-} chain, the classical ground state is not an eigenstate of H. In

1931, Bethe found the ground state eigenfunction of the spin-! chain, and showed

that it was not ordered: that is. this chain does not exhibit long-range order even

at T = 0 [9]. Given this, the physical nature of the T = 0 excited states is not

clear. Nevertheless, des Cloizeaux and Pearson [10] have computed the dispersion for

the low-lying excited states and found w o( Isin kal, which is the same k dependence

found if one assumes the classical ground state for T = 0 and computes the spin wave

spectrum [11]. However, there are some differences between the true excited states

and the classical ones (for example, the true first excited state is a triplet, whereas

the classical state is a doublet), and the physical nature of the excitations remains

unclear. Again using a naive Debye-like model to obtain the temperature dependence

of specific heat, one expects c cx T (for w c< k dispersion, valid for long wavelengths).

Surprisingly, this temperature dependence is confirmed by the Bonner and Fisher

results, although the amplitude of the linear term is a factor of three smaller than the

spin wave result (experiment also supports the Bonner and Fisher results [1]). The

Bonner and Fisher result is shown in Figure 1-3.

To summarize, the 1D classical model yields the AF and FM ground states that

we intuitively expect, and shows high-temperature behavior that approximates the

behavior of chains with S = 5 and larger. However, its low-temperature behavior is

unphysical, and its thermodynamics is the same for both AF and FM chains. The

spin-- FM ground state is the same as the classical one, and the T = 0 excitations

are spin waves, each of which lowers the total spin of the chain by one quantum. At

temperatures much above T = 0. it is not clear that the simple spin wave picture

is valid; however, it gives a qualitative account of the low-temperature specific heat.

For the spin-j AF, the ground state is not the same as the classical one; moreover,

it is disordered. However, assuming the classical ground state and computing the

resulting spin wave spectrum again leads to an accurate qualitative account of lowtemperature specific heat. For our purposes, the most critical feature of the quantum

picture is the result that the excitations near T = 0 are spin waves, with differing

dispersions for the FM and AF cases.

1.2

Sr 3 CuPt 1 _pIrpO

6

Sr 3 CuPt 1 _pIrpO 6 is one member of a family of new one-dimensional magnetic ma-

terials with general formula Sr 3 MM'O 6 , where M and M' refer to sites in the crystal structure that will accept various magnetic and non-magnetic ions. Work on

Sr 3 MM'0

6

began in 1991 with the discovery of Sr 3 CuPtO6 by Wilkinson et al. [12].

Soon after, Nguyen and zur Loye [13] began a systematic study of the synthesis

and magnetic properties of several members of this family, including Sr 3 CuPtO6 ,

Sr 3 CuIrO6 , and their alloy Sr 3 CuPtlpIrpO6 .

The general crystal structure of Sr 3 MM'0

6

is shown in Figure 1-5. The struc-

ture consists of chains of alternating face-sharing MO 6 trigonal prisms and M'0 6

octahedra, with the chain axis parallel to the c-axis of the crystal. In the ab plane,

one sees a hexagonal net of chains, with each chain surrounded by six clusters of

26

G *

Q

0)

fiU:

06.

k

C9 *

Figure 1-5: Crystal structure of Sr 3 MM'0

6

. Left: view along the length of a chain,

showing alternating MO 6 trigonal prisms (M represented by the small ball at center of

prism) and M'0 6 octahedra (M' represented by the large ball at center of octahedron).

Right: view down the c axis. Clusters of 3 Sr ions surround each chain.

27

three Sr+ ions. Typically, a = 9.6)1, while c = 11.2A (c = 6.7 A for Sr 3 CuPtO6 and

Sr 3 CuIrO6 ) [13] [14]. c is four times the distance between M and M', due to the geometry of the trigonal prism and octahedron. Hence the magnetic ions on the M and

M' sites are at most 2.8A apart, whereas sites on different chains are 5.5A apart. The

separation between these two distance scales leads one to expect that the magnetism

of these materials will be one-dimensional over some temperature range.

Interest in Sr 3 CuPti1 ,IrO 6 in particular was motivated by measurements of Ml/H

at low fields (below 10kG) and at temperatures 2K < T < 300K for Sr 3 CuPtO6 ,

Sr 3 CuIrO6 , and Sr 3 CuPtjpIrpO6 . Nguyen [13] found that NI/H for Sr 3 CuPtO6 fit

well to a one-dimensional AF Heisenberg model, with IJI/kB = 26.1K. For Sr 3 CuIrO6 ,

Nguyen hypothesized that M/H showed one-dimensional FM behavior, with the peak

in MT/H indicating a coupling on the order of J/kB ~ 30K. However, measurements

of M/H on Sr 3 CuPti_pIrpO 6 showed Curie Law behavior down to 2K (Figure 1-6).

This was quite surprising, given that J for the parent materials was around 30K.

The chemistry of Sr 3 CuPtO6 indicates that a Cu2+ ion, with spin-), will be located

in the M site. Cu 2 + generally behaves as a Heisenberg spin- [1]. Pt 4 + is located in

the M' site, and has spin zero. Hence the AF behavior of Sr 3 CuPtO6 can be explained

if two Cu 2+ on nearest M sites interact via superexchange through the Pt 4 + on the

intervening M' site. Since superexchange is always an AF interaction [7], and since

the M-M' distance is only 1.71 in Sr 3 CuPtO6 , this explanation is reasonable.

The chemistry of Sr 3 CuIrO6 leads to a spin-1 Cu 2 + ion occupying the M site in this

material as well. The M' site will be occupied by Ir4+, which also has spin-!. The FM

behavior of Sr 3 CuIrO6 can be explained if the nearest-neighbor Cu 2 + and Ir 4 + ions

interact ferromagnetically via direct exchange, which is reasonable given the Cu2+_

Ir 4 + distance of 1.7A. Magnetization versus field data at 5K for Sr 3 CuIrO 6 shows

that only one-third of the full moment 2 p, is obtained for fields up to 20T in powder

samples [15].

If Sr 3 CuIrO6

were a Heisenberg FM, there would be no preferred

direction and it would be possible to achieve the full moment in the powder samples

at reasonably low field. This result suggests that there is some strong anisotropy in

Sr 3 CuIrO6 that restricts the spins to align along a particular direction in the crystal.

One possible reason for this anistropy is ferrimagnetic ordering of Ising-like spins

on a hexagonal net. Such ordering could occur in Sr 3 CuIrO6 if a strong, AF, Ising

coupling existed between short FM segments in different chains. Magnetization data

on Ca 3 Co 2 0 6 [16], which is isostructural with Sr 3 CuIrO6 , has been interpreted in

terms of this type of Ising ferrimagnetism. Of course, if ferrimagnetism is the correct

explanation of the M versus H data, then Sr 3 CuIrO6 is not one-dimensional below

5K.

On the other hand, this does not mean that Sr 3 CuPt0 .5 Ir 0 .5 0 6 could not be

one-dimensional below 5K. In any case, possible consequences of such anisotropy for

Sr 3 CuPt0 .5 Ir 0 .5 O6 will be discussed further in Chapters 2 and 7.

Given the magnetic structure of Sr 3 CuPtO6 and Sr 3 CuIrO 6 , we expect the alloy

CuPtj.pIrpO

Sr 3

6 to consist of spin-! chains with a random distribution of nearest-

neighbor FM and AF bonds, with probability p that a given bond is FM, 1 - p that it

is AF. This model has been considered theoretically by P.A. Lee and his collaborators

in a series of papers, and will be discussed in detail in Chapter 2. This theory was

found to give a good account of the unusual Curie Law behavior (Figures 1-7 and

28

Sr 3 CuIrO6

Sr 3 CuPtO6

0.006.

0.6 -

I =:.Z1:u6.1 K

0.005 -

K

S

0.004 -

0 0.4

-

0.003 S

0.2

0.002 -

S

I-D Halse::er3 Modei

0.001

6

50

100

150

:00

Temperaturz

250

Sp*------

0.0

300

0

5b

100

K

150

200

250

300

Temeraure(Kj

Sr3 Cu Pt 0 .I r05 0 6

0.04

0-

E 003

0

E 0.02

*

0.01

-

*@*00...

0

0

Figure 1-6:

10 20 30 40

Temperature [K]

50

M/H data for (top left) Sr 3 CuPtO6 , (top right) Sr 3 CuIrO6 , and

Sr 3 CuPtO.5 IrO. 5 0 6 (bottom).

29

1-8), and made several predictions about the low-temperature (< 2K) properties of

the alloy. In particular, the alloy was predicted to have an unusually large spin

entropy content at low temperatures (10 - 30% of R ln 2, depending on p), and at

the lowest temperatures to exhibit behavior characteristic of a new universality class

of random quantum spin chains, with characteristic scaling laws in specific heat and

susceptibility.

800

*

Sr 3 CuPtO6

A

Sr 3CuPto.75Iro.2506

I

Tv Sr 3CuPto.soIro.5006

600

+

Sr3CuPto.:Iro.75Ose6

*

SrsCuIrO6

*

A

A

F

A

*V

A

400

A

A

V

I

A

V

U

A

A

A

V

200

A*

VT

:

T

.MMMMU

0

0

50

100

150

200

250

Temperature (K)

Figure 1-7: 1/x data for Sr 3 CuPtl-,IrO 6 taken by Nguyen [15].

30

300

20.0

15.0

h

10.0 -

5.0

p=1

0.0

0.0

4.0

8.0

4k BT/J

Figure 1-8: 1/x theoretical prediction of Lee and collaborators [17].

31

1.3

Specific Heat of Sr 3 CuPt0 5. 1r0 .o5 0 6 below 1K

The goal of this work is to investigate the specific heat of one particular alloy,

Sr 3 CuPt 0 .5 Ir 0 .5 0 6 , at temperatures below 1K.

Of course, one reason to measure

specific heat of Sr 3 CuPto.5 Iro. 5 0 6 below 1K is to discover whether it is a material that obeys the theory. However, there is another reason for interest in

Sr 3 CuPto.5 Iro. 5 0 6 (and Sr 3 CuPtipIrpO6 in general).

If it does obey the theory, or

at least is found to have a substantial low-temperature entropy content, the material

may be useful for refrigeration via adiabatic demagnetization. Adiabatic demagnetization of paramagnetic salts was the only technique available for refrigeration below

300mK until the early 1970's, when dilution refrigerators became widely available.

However, most dilution refrigerators do not provide access to temperatures below

10mK, and for temperatures below 1mK the only known refrigeration technique is

nuclear demagnetization [18]. The hope is that Sr 3 CuPt 0 .3Ir0 .3O6 may prove superior in some way to dilution refrigerators or paramagnetic salts in the 10mK - 1K

range, or that it may even provide competition for nuclear demagnetization in the

low millikelvin to 100pK range.

Sr 3 CuPt0 5 Ir 0. 5 0 6 is focused on for two reasons: first, the most extensive experi-

mental work thus far has been done on Sr 3 CuPto.5 Iro. 5 0 6 ; second, the distribution of

FM and AF bonds in this particular alloy is (in principle) completely random. Specific

heat is measured for several reasons. First, no other groups have yet reported specific heat measurements on Sr 3 CuPt 0 .5 Ir 0 .5 0 6 below 1K. Second, specific heat gives

the most direct access to entropy content. Third, if Sr 3 CuPt 0 .5 Ir 0 .5 0 6 undergoes a

transition to long-range (two or three-dimensional) ordering at some temperature,

specific heat provides a definitive signature for such a transition. Finally, if there are

phases in addition to pure Sr 3CuPto.5 Iro. 5 0 6 or magnetic impurities of some kind in

the measured Sr 3 CuPto.5 Iro.05 6 sample, these are likely to have lower entropy content

than Sr 3 CuPt 0 .5 Ir 0 .30 6 . Therefore the presence of such phases should not confuse the

comparison of the specific heat data with theory.

In order to achieve this goal of specific heat measurements on Sr 3 CuPt0 .5 Iro. 5 0,

it was necessary to design, build, and test a new experiment for specific heat measurements below 1K. The resulting apparatus allows for specific heat measurement

from 100mK to 2K in magnetic fields to 7T using either AC or relaxation calorimetry.

While based on earlier designs, the apparatus has a few unusual features. In particular, it allows for accurate AC calorimetry below 1K, incorporates a non-destructive

sample mounting technique, and uses a new arrangement for relaxation calorimetry. The experiment was tested by measurements of the field-dependent specific heat

of potassium ferricyanide K3 Fe(CN) 6 , a common material used in blueprinting and

photography that behaves as a one-dimensional Ising AF below 1K and has a (threedimensional) Nel transition at 130mK.

This work is organized as follows. In Chapter 2, I discuss the theory of random

quantum spin chains, developed by P.A. Lee and his collaborators, and experimental

work to date on Sr 3 CuPti-IrpO6 . In Chapter 3, I describe in detail the two methods used to measure specific heat, and mathematical models for these methods. In

Chapter 4, the design and construction of the apparatus is described. In Chapter

32

5, measurements and results on K3 Fe(CN) 6 are described, and in Chapter 6, measurements and results on Sr 3 CuPtO.*

5 ro. 5 0 6 . Finally, in Chapter 7 I conclude with a

presentation of the final results for specific heat of Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1ro. 5 0 6 , discussion of

the results, and recommendations for future work.

33

34

Chapter 2

Random Quantum Spin Chains

and Sr 3 CuPtipIrpO6

2.1

Theoretical Work on RQSC

The statistical mechanics of random quantum spin chains has been studied by

Lee and collaborators [19] [5] [20] [21] [22] in a series of papers. They modeled

Sr 3 CuPtIIrpO6 as a spin-! Heisenberg chain with Hamiltonian

L--

'=

L-1

JiSi - Si+ - MHz E SZ

i=O

(2.1)

i=O

The Ji are given by the probability distribution

P(Ji) = p3(Ji + J) + (1 - P) (Ji - J)

(2.2)

This distribution indicates that a given nearest-neighbor bond will be of strength J

and have probability p of being ferromagnetic and probability 1 -p of being antiferromagnetic. Hence the chain can be pictured as a collection of connected ferromagnetic

and antiferromagnetic chain segments, where the typical lengths of the FM and AF

segments depend on p.

Furusaki et al. applied high-temperature expansion [23] [24] and transfer matrix

methods [25] [26] [27] to analyze this system, and postulated the following physical

picture based on their numerical results. For kT > J, the spins are decoupled and

the system behaves as an ordinary paramagnet. For kBT < J, FM or AF correlations grow within the segments. Excitations of very short segments (a couple spins

in length) will have energies of order J, and so will not contribute significantly to the

thermodynamics in this temperature range. Longer segments can be described in a

spin wave picture, with a spin wave population in each segment determined by kBT,

the length, and the type (FM or AF) of segment. Since FM and AF segments have

different spin waves dispersions, a spin wave from a FM segment will not propagate

into the adjacent AF segments (and vice vesa) (Figure 2-1). Hence the thermodynamics of the system in this temperature range is the same as that of a collection of

relatively short, decoupled segments. Since the segments are relatively short, there

35

is a substantial energy gap between the ground (zero spin wave) state and the first

excited (one spin wave) state. Hence for kBT < J, these decoupled segments will

be found in their local ground (zero spin wave) state, which is the state of maximal

(minimal) total spin for a FM (AF) segment. In this low temperature regime, a FM

segment containing n sites (for example) therefore behaves like a single "large spin"

of spin n/2.

Figure 2-1: Schematic view of spin wave confinement. Due to different dispersion

relations for FM and AF segments, spin waves from a given segment do not propagate

into adjacent segments. A mechanical analogy is a rope with discontinous changes in

thickness.

One might wonder whether the presence of these decoupled. large spins could be

detected via a change in. for example, the Curie constant c = xT. The argument is

most easily made for classical spins of magnitude So at each site rather than quantum

spins-! as is the real case for Sr 3 CuPt 1 -IrpO

6

; however, the argument holds for the

quantum case as well [17]. For kBT > J, the susceptibility per site x/N is just

2S2

x/N

=

2

3kBT

(2.3)

3kBT

For kBT < J, short range order forms, with neighboring spins locked either parallel or

antiparallel to each other (depending on whether their bond is FM or AF) in clusters

of length (the correlation length). Note that these clusters will contain both FM

and AF bonds-in the classical case, the spin wave picture does not apply and so there

is no decoupling of FM and AF segments. In fact, a simple change of variables maps

the classical problem to a simple classical FM chain without changing the energy

spectrum [19]. However, these clusters form an effective spin Seff. To compute Seff

for p = 0.5, one moves from one site to the next in the cluster, adding the spin at

each site to Seff. For p = 0.5, there is an equal probability of increasing or decreasing

Seff by one unit at each site. Therefore (S'2f) can be computed in a random walk

36

picture, with the result (Sjff) = So. In this case the total susceptibility is

x

-

N /p (2n f)

B(Sf

3kBT

(2.5)

Hence the susceptibility per site is

xN

(BSo)

2

(IB So) 2

3kBT

(2.6)

(2.7)

The Curie constant is the same for the two temperature regimes. For a quantum spin

S, the Curie constants are slightly different- for kT > J, S2 is replaced by S(S +1)

above, and for kBT < J So is replaced by S [17].

Furusaki et al. found that their numerical methods began to fail at an energy scale

kBT

-

J/5, and that the entropy per site obtained by integrating C/T from infinite

temperature down to J/5 was less than the total entropy per site kBln2. The amount

of this "missing" entropy varied with p: 12%, 24%, and 36% for p = 0.25, 0.5., 0.75

respectively. As a test of their physical picture of decoupled segments, they assumed

that this picture applied at J/5 and computed the amount of entropy in the decoupled

segments. A match between this amount and the amount "missing" from the HTE

and TM calculations would lend credence to the decoupled segments picture.

In order to compute the amount of entropy in the decoupled segments picture,

Furusaki noted that a FM segment containing I bonds has entropy kB In 1, an AF

segment with I odd has zero entropy, and an AF segment with 1 even has entropy

k, ln 2. (Furusaki determined that the boundary spins, which are shared by adjacent

FM and AF segments, must be assigned to the AF segment.) Then the entropy

contribution per site is given by

S= E

N

(2.8)

where the sum is over all segments, and N is the total number of sites in the chain.

This can be rewritten

S

+

ZAFsegs nAF +

AFsegs SAF

ZFMsegs SFM

FMsegs nFM

(2.9)

that is, the sums are taken over the AF and FM segments separately. Noting for

example that EFMsegs nFM

=

(nAF)N,AF, where Ns,AF is the number of AF segments,

and that the number of FM segments is equal to the number of AF segments (they

may differ by 1, which can be neglected for a chain with a large number of sites),

+ (SM)(2.10)

(rAF)+ (rFM)

S(SAF)

37

Given the probability densities for FM and AF segments with 1 bonds,

PF(1)

=

PA (l)

=

(2.11)

(2.12)

- P)P'1

p(1 - p)'

the quantities in (2.10) are found to be

00

(SAF)

(2.13)

A (2m)

ln(2S +1)

m=1

(2.14)

PF(l) ln[2S(l - 1) + 1]

(SFM)

11

1

(nAF)

+p

(2.15)

p

(nFM)

(2.16)

i-p

From these, s can be computed as a function of p. Good agreement is found between

s(p) found in this way and the amount of missing entropy found by Furusaki et al.

from their HTE calculations (Figure 2-2). Hence the decoupled segment picture seems

to provide a reasonable model for this low-temperature (kBT < J/5) regime.

I

I

I

I

I

I

'

0.4

0

Model

o HTE

U.3

0.2

<1

0.1

0

I

0

I

0.2

I

I

I

0.4

0.6

0.8

I

1.0

P

Figure 2-2: Missing entropy as a function of p, calculated with (line) Equation 2.10

and (open circles) HTE.

Since there is no frustration in this disordered system, one expects all of the

missing entropy to be removed from the system between kBT

38

-

J/5 and T = 0 .

Furusaki et al. proposed that the coupling between segments, while much smaller

than J, is not zero. To test this proposal, they carried out exact diagonalization of

Hamiltonians of finite length chains (around 10 spins) with various configurations of

FM and AF bonds, and found that in the ground state adjacent segments were indeed

coupled. Accordingly, the lowest-lying excited states were intersegment spin waves,

that is spin waves in which total Sz, summed over all large spins in the chain, was

reduced by 1 for each spin wave. These low-energy spin wave excitations were of course

at much lower energy than spin wave excitations within an individual segment, where

S, of an individual large spin is reduced. Hence the "missing" entropy remaining

below J/5 would be removed from the system by correlations between the segments

that arise at much lower energies (temperatures) than the correlations within the

segments. The sign and strength of the couplings between segments depended on the

ordering (FM or AF) and size of the adjacent segments.

This work on exact diagonalization of finite chains motivated Westerberg et al. to

consider the Hamiltonian

'=

JiSi

(2.17)

where the magnitude and sign of the Ji and the size of the spins Si are random

(Figure 2-3). Here, the Si represent the large spins discussed above. Westerberg

et al. took this Hamiltonian to model the low-energy properties of the RQSC, and

attacked it using a generalization of the real-space renormalization group (RSRG)

method developed by Dasgupta and Ma [28] for the study of random AF spin-!

Heisenberg chains. The physical rationale for the RSRG is that at a given temperature

T, the spins coupled by J, > kBT will have frozen into their local ground state, and

the thermodynamics will be determined by spins coupled by Ji < kBT. Hence as the

chain cools, the spins remaining to participate in the thermodynamics will be coupled

by progressively weaker Ji, and the distribution of spin sizes and bond strengths will

change (see Figure 2-4).

1

2

1/2

5/2

0

6

0

Figure 2-3: Spin chain considered by Westerberg et al. (Equation 2.17). The FM

segments form large effective spins, separated by AF segments of variable length.

39

SL

S1

A1

SR

A0

S2

A2

RENORMALIZE

SI

SL+ SR

A1

S2

A2

Figure 2-4: Schematic of the RSRG method. A renormalization step proceeds by first

identifying \O, the strongest bond in the chain. Then the two spins linked by .\o are

frozen to form an effective spin SL +SR, and the nearest neighbor bonds renormalized

to i\1 and Z12 . As the chain cools below kBT - Ao, it effectively carries out a step in

the RSRG.

40

They found that the distributions of spin sizes and bond strengths in the chain

flow to fixed-point distributions as the RSRG proceeded. From these fixed-point

distributions of spins and bonds, scaling laws governing the thermodynamic properties

of the system in the universal regime can be computed. For finite temperature T,

large spins coupled by bonds weaker than kBT can be considered to be free spins,

since in the universal regime the bonds are typically much weaker than kBT. Hence

the (zero-field) entropy per site will be given by

s(T, H = 0)/L oc keln(2(S) + 1)/n

(2.18)

where (S) is the average spin size (computed from the distribution found via RSRG),

and n the number of spins-! per large spin. In the universal regime, they found

n ~0 2, where A0 is the strongest bond in the chain and a = 0.22 ± 0.01. Also,

(S) ~ A . Hence

s(T, H = 0)/L oc akBT 2, | InT

(2.19)

and for the specific heat

-(T)/L oc| InT IT

(2.20)

The effect of an applied field H will depend on how the magnetic energy p(S)H

compares with kBT. If p(S)H < kBT, the field will not be able to overcome the

thermal fluctuations of the free spins, and the specific heat will still be given by

(2.20). On the other hand if p(S)H > kBT, then the field will start to align spins

with couplings of A0 ~ p(S)H or less. Using the scaling result for (S), the energy

scale at which the field starts to align spins is thus AH ~ H 1/(1+"). Hence if one were

to study, as a function of applied field, the temperature at which the entropy started

to decline rapidly, one would find the relation T ~ H1/('+").

The work of Westerberg et al. provides at least two methods to search for evidence

of universal behavior via specific heat. First, one could simply measure specific heat

as a function of temperature in zero field and look for the expected dependence given

by equation (2.20). Second, in an applied field one should find a peak-like structure

in the specific heat at a temperature corresponding to the energy scale Ao' described

above. By studying the way in which the temperature at which this peak occurred

varied with field, one could attempt to verify the relation T ~ H1/(1+c).

Further theoretical work on the RQSC was done by Frischmuth and Sigrist [22].

They applied the continuous time quantum Monte Carlo loop algorithm [29] to the

Hamiltonian (2.17) and assumed an initial distribution

P (J)=

1 -J 0 < J < Jo

0, otherwise

2J'

This initial distribution was chosen so that the algorithm would be accurate well

into the universal regime and because Westerberg's theory should apply to it. Hence

Frischmuth and Sigrist's results provide an independent check on Westerberg et al.'s

work. Frischmuth and Sigrist found that their results agreed very well with those

of Westerberg; in particular, they found a = 0.21 ± 0.02, whereas Westerberg found

41

a = 0.22 ± 0.01.

The theory presented above provides a consistent description of systems with

Hamiltonian given by (2.1). Experimentally, it is critical to know whether and how

the theory applies to Sr 3 CuPtiJIrpO6 in particular. Note that the Hamiltonian differs from Sr 3 CuPt1_JIrpO 6 in at least four ways: first, the magnitude of the Ji are

different for FM (50K) versus AF (26K) bonds; second, the FM bonds always occur

in pairs; third, in light of the high-field magnetization data on Sr 3 CuIrO 6 (Chapter 1),

it is not clear that it is appropriate to treat the FM segments as Heisenberg; finally,

couplings between the chains are neglected. Regarding the first two differences, it

is thought [5] that bond randomness is the factor that will determine the physics of

Sr 3 CuPtjJIrpO6 . Hence, within certain limits, the quantitative details of the bond

distributions will not change the basic physical description of the system as given by

the model. Regarding the third difference, the theory requires that some kind of spin

wave picture can be used to describe the FM segments. This will be the case if the

FM interaction is Heisenberg or XY [30], but not if it is Ising. The fact that the theory gives an account of the high-temperature data (see Figures 1-7 and 1-8) suggests

that a spin wave picture does apply, at least in that temperature range. More measurements may help to clarify the situation. For example, high-field measurements

on Sr 3 CuIrO6 well above 30K would be desirable as a control on the 5K result, as

would high-field measurements at high and low temperature for Sr 3 CuPtO.5 1r o.5 0 6 it-

self. As for the fourth difference, since the distance between chains is large (10A),

wave functions of electrons on different chains will not overlap directly. Hence the

chains will not interact via exchange interactions. A band structure calculation (using

the extended Hiickel method) for an isolated NiPtO6- chain and for Sr 3 NiPtO6 [31]

shows that the band structure for an isolated chain is virtually identical to a chain in

Sr 3 NiPtO6 . It also shows that there are very few Sr states available at the energies

occupied by the unpaired Ni electrons. The Sr is therefore unlikely to perturb the Ni

electron wave function, so no superexchange coupling via the Sr is expected. Hence

the strongest interchain interaction will be the magnetic dipole interaction. This can

be estimated via [6]

a

1

U ~

(2.21)

13 7 ()(Ry

where r is the distance between moments and Ry the Rydberg constant. Naively

plugging in the interchain distance for r, U ~ 1OmK. Hence it is at least plausible

that Sr 3 CuPtJIrpO6 will remain one-dimensional down to the lowest temperatures

accessible by a dilution refrigerator.

Pursuing the question of couplings between chains further, the temperature T,

at which a system consisting of one-dimensional chains is expected to undergo a

transition to long-range, three-dimensional order is given by [2]

kBT ~ J's2 d(T)

(2.22)

where s is the spin at a site in the chain, J' the coupling between chains, and 1d

the correlation length. This result is obtained from the simple argument that as

correlations grow within the chain, the correlated sections can be treated as a single

42

large spin of magnitude s 1d, and that three-dimensional order will occur when the

interaction between two such large spins in adjacent chains is comparable to the

thermal energy. This "amplification" of T, by 1d should be quite large for p = 0, 1,

whereas for intermediate values of p the bond disorder will limit 1d. Hence one might

expect an interesting dependence of T, on p, which might give one some indication of

the sizes of the large spins in the chains at the given p.

Ramirez has measured low-temperature specific heat on Sr 3 CoPtO6 [15], in which

cobalt has spin 2 and platinum spin zero or spin 1. This material was thought to be

a possible example of a classical random spin chain, for which Lee and collaborators

have also made predictions [19]. Ramirez found a long-range ordering transition at

1.4K [32]. Using the classical expression for 1d [2], and the measured Tc, I find

J _ 4mK. This result lends further support to the conjecture that the coupling

between the chains is very weak. I emphasize that for a classical chain, as discussed

above, the disorder does not limit the size of (T), so one would expect a higher T,

for the classical system than for Sr 3 CuPt 1 _pIrpO 6 .

However, even if there are no materials properties of Sr 3 CuPt 1 _,IrpO 6 that obvi-

ate its description by the theory, the energy scale at which the actual distributions

of bonds and spin sizes for Sr 3 CuPt 1 _pIrpO 6 begin to match those of the universal

distribution may be experimentally inaccesible. Westerberg et al. attempted to address this issue by beginning the RSRG procedure with a distribution simulating

Sr 3 CuPt1pIrpO6 for p = 0.8. They found that the approach to the universal distribution was very slow; indeed, (S) and (n) do not show pure scaling behavior until

Ao/J ~ 101. For J ~ 40K, this leads to temperatures clearly below anything

available experimentally for condensed matter systems. Nevertheless, measurements

in the experimentally accessible temperature range are of value as a test of the theory

(for example, what if scaling behavior was observed at an accessible temperature?),

and to determine the true low-energy physics of Sr 3 CuPt 1 _,IrpO 6 (for example, it may

undergo a phase transition to long-range, three-dimensional order).

2.2

Experimental Work on Sr 3 CuPt1_pIrpO 6

As mentioned in Chapter 1, DC magnetic susceptibility for temperatures 2K < T <

300K has been measured for Sr 3 CuPt1_pIrpO 6 with various p and compared with the

theory of Furusaki et al.. Excellent qualitative agreement between the kBT > J/5

theory of Furusaki et al. and experiment was found [17]. (see Figures 1-7 and 1-8).

These results encouraged further experimental study of Sr 3 CuPt 1iIrpO

6

, particularly

at lower temperatures where the decoupled segment picture and the theory of Westerberg et al. might apply. AC susceptibility of p = 0.5, 0.667 samples has been measured

on 50mK < T < 30K and in fields OkG < H < 2kG by Beauchamp and Rosenbaum.

Also, specific heat of a p = 0.5 sample has been measured on 2.5K < T < 50K in