Prooxidant Effects of Ferrous Iron, Hemoglobin, and Ferritin in Oil

advertisement

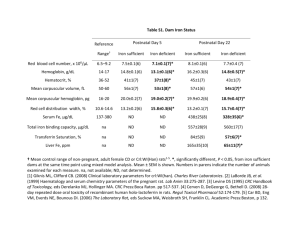

Prooxidant Effects of Ferrous Iron, Hemoglobin, and Ferritin in Oil Emulsion and Cooked-Meat Homogenates Are Different from Those in Raw-Meat Homogenates1 D. U. AHN,*,2 and S. M. KIM† *Animal Science Department, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 50011, and †Food Science Department, KyungSan University, KyungSan, Korea ascorbate was present. Hemoglobin and ferritin had no prooxidant effect in raw-meat homogenates. The status of heme iron and the released iron from hemoglobin had little effect on the prooxidant effect of hemoglobin in oil emulsion and cooked meat homogenate systems. The prooxidant effect of ferrous iron in oil emulsion and cooked-meat homogenates disappeared in the presence of superoxide (.O2–), H2O2, or xanthine oxidase systems. In raw-meat homogenates, however, ferrous had strong prooxidant effects even in the presence of .O2–, or H2O2. The status of free iron was the most important factor in the oxidation of oil emulsion and cooked-meat homogenates but the impact in raw-meat homogenates was small. ABSTRACT Oil emulsion and raw and cooked tissue homogenates were used to determine the mechanisms of various iron forms on the catalysis of lipid peroxidation. Flax oil (0.25 g) was blended with 160 mL maleate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.5) to prepare an oil emulsion. Raw or cooked turkey leg meat was used to prepare meat homogenates. Samples were prepared by adding iron from each of the various sources, reactive oxygen species, or enzyme (xanthine oxidase and superoxide dismutase) systems into the oil emulsion or meat homogenates. In oil emulsion and cooked-meat homogenates, ferrous iron and hemoglobin had strong prooxidant effects, but ferritin became prooxidant only when (Key words: hydrogen peroxide, superoxide, iron sources, oil emulsion, meat homogenates) 1998 Poultry Science 77:348–355 hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to form hydroxyl radicals (.OH). Ahn et al. (1993a), on the other hand, found that iron chelated to iron binders or storage proteins had very weak or no catalytic effect on lipid peroxidation reaction. Halliwell and Gutteridge (1986) showed that transferrin, an iron carrier protein that binds ferric iron tightly, did not participate in .OH generation at physiological concentrations. The work of Baldwin et al. (1984) indicates that partly saturated transferrin protects cells from damage by binding iron that might catalyze .OH formation from superoxide (.O2–) and H2O2. Transferrin, however, can release iron at low pH (below pH 5.6) and thus can accelerate lipid peroxidation under those conditions. Ferritin is regarded as a safe iron storage protein, but has been shown to be involved in the formation of .OH, if the iron ions are released from ferritin by ascorbate, dithionite, or .O2– radicals (Carlin INTRODUCTION Organic and inorganic iron compounds are involved in the catalysis of various stages of lipid peroxidation; however, the catalytic effects of free ionic iron (both ferric and ferrous irons), bound iron, and heme pigments on lipid oxidation, and the mechanisms by which the lipid peroxidation is catalyzed, are still controversial. Kanner et al. (1988) reported that free ionic iron is the major catalyst for lipid oxidation in meat products. Johns et al. (1989), however, found that all forms of inorganic iron have little prooxidant activity in exhaustively washed muscle fibers and concluded that heme pigments are more powerful catalysts of lipid oxidation than inorganic iron compounds. The work of Halliwell and Gutteridge (1990) indicates that all of the simple iron complexes are capable of decomposing Received for publication January 13, 1997. Accepted for publication October 7, 1997. 1Journal paper Number J-16849 of the Iowa Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station, Ames, Iowa. Project Number 2794, and supported by Hatch Act, NC-183 and State of Iowa funds. 2 To whom correspondence should be addressed: duahn @iastate.edu Abbreviation Key: BHA = butylated hydroxyanisol; DDW = deionized distilled water; Hb = hemoglobin; MDA = malonaldehyde; SOD = superoxide dismutase; TBA = 2-thiobarbituric acid; TBARS = 2-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; TCA = trichloroacetic acid; XOD = xanthine oxidase. 348 PROOXIDANT EFFECTS OF IRON SOURCES IN DIFFERENT TESTING SYSTEMS and Djursater, 1984; Biemond et al., 1986; Decker and Welch, 1990). Hirano and Olcott (1971) reported that heme with iron in either the ferrous or ferric states was an effective catalyst in lipid oxidation to unsaturated fatty acids. Kaschnitz and Hatefi (1975) reported that only the ferric forms of hemes were active catalysts of lipid oxidation in muscle. Others (Sato and Hegarty, 1971; Love and Pearson, 1974; Ahn et al., 1993b) found that heme pigments have little influence on the development of offflavors or 2-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in meat. Hidalgo et al. (1990) suggested that heme proteins may compete with other molecules for oxidant radicals and, thus, serve as antioxidants. Kanner and Harel (1985) showed that metmyoglobin alone had no effect on membranal lipid peroxidation, but that metmyoglobin activated by H2O2 had a significant effect. The interaction of natural heme pigments with H2O2 produces an active species that can initiate lipid peroxidation (Kanner and Harel, 1985). The incubation of heme pigments with a molar excess of H2O2 or heating could release ionic iron from heme (Chen et al., 1984; Gutteridge, 1986), which can catalyze lipid oxidation. Addition of NaCl into meat during processing procedures significantly increases the release of free ionic iron from heme pigments or other binding macromolecules (Kanner et al., 1991; Ahn et al., 1993b). According to Haber-Weiss reaction [4] (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1990), .O2– reduces ferric iron to the ferrous form [1], and ferrous iron splits H2O2 formed by the reaction [2] to produce .OH radicals, which catalyze lipid oxidation. .O2– + Fe3+ → Fe2+ + O2 [1] .O2– + 2H+ → H2O2 [2] H2O2 + Fe2+ → Fe3+ + OH– + .OH .O2– + H2O2 → OH– + .OH (metal catalyst) [3] [4] Miller et al. (1990), however, rejected the traditional Fenton type reaction [3] (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1990) and suggested that an Fe(II):Fe(III) complex is the catalyst of lipid oxidation. Other researchers (Kanner and Harel, 1985; Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1990; Shen et al., 1992) also suggested that the initiator of lipid oxidation formed from the reactions [3] and [4] is not .OH but ferryl or perferryl radicals, and the iron involved could be free or bound and heme irons. Various systems used to study the catalytic effect of iron sources, and the controversial results from those studies suggesting that iron sources may have different catalytic effect in different study systems. Also, the mechanisms 3Fisher 4Sigma Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA 15219-4785. Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO 63178-9916. 349 by which lipid oxidation is initiated and propagated could be affected by the study systems, iron sources, and other conditions. The objectives of this study were: 1) to determine the mechanisms of various iron forms on the catalysis of lipid peroxidation in oil emulsion, and raw and cooked tissue homogenates; and 2) to find the effect of various conditions on the release of iron from iron proteins and its consequence on the catalysis of lipid peroxidation in oil emulsions and raw and cooked tissue homogenates. MATERIALS AND METHODS Chemicals Ascorbate was purchased from Fisher,3 and butylated hydroxyanisol (BHA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), xanthine, xanthine oxidase (XOD), catalase, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA), chelex-100 (50-100 mesh, sodium form), ferrozine (3-(2-pyridyl)-5,6-bis (4phenyl sulfonic acid)-1,2,4-triazine, and neocuproine were obtained from Sigma.4 All chemicals used were reagent grade. Reagents Ascorbate (1,000 ppm), SOD (100 U/mL), xanthine (40 mM), XOD (4.528 U/mL), desferrioxamine mesylate (20 mM), and potassium superoxide (KO2, 14 mM) were prepared by dissolving the appropriate amount of each chemical directly in deionized distilled water (DDW). Fifty parts per million iron (0.895 mM) equivalent solutions were prepared by dissolving the appropriate amount of each protein in distilled water [hemoglobin (Hb), 15.6 mg/mL; ferritin, 250 mg/mL]. The ionic iron solutions were prepared by dissolving 178 mg FeCl2.4H2O or 242 mg FeCl3.6H2O in 1 L of 0.1 N HCl to make 50 mg Fe/mL (0.895 mM) solution. The TBA/TCA stock solution was prepared by dissolving 15% TCA (wt/vol) and 20 mM TBA in DDW. Seventy-five milligrams of ferrozine and 75 mg neocuproine were dissolved in 25 mL DDW to make ferroin color reagent (Carter, 1971). The BHA (72 mg/mL) was dissolved in 97% ethanol. Sample Preparations For the oil emulsion, 50 mL Tween-20 was dissolved in a 250-mL beaker containing 20 mL DDW and 8 mL 1 M maleate buffer, pH 6.5, and then 0.25 mL oil (flax oil) was added dropwise while stirring. Maleate buffer was chosen in this study because it has relatively high buffering capacity at pH 6.5 range, and has no iron chelating effect. After 5 to 10 min of mixing, two to three pieces of KOH (about 0.4 g) were added to improve saponification. After mixing for 5 min, the volume of the oil emulsion (pH 10 to 11) was adjusted to 160 mL by slowly adding Chelex100-treated DDW. The pH of the diluted emulsion was adjusted to pH 6.5 with 5 N HCl and then used 350 AHN AND KIM immediately for the subsequent study. Addition of KOH improved emulsification of oil but had no effect on the rate of lipid oxidation. The flax oil used in this study was composed of 5.42% C16:0, 2.69% C18:0, 12.08% C18:1n9, 16.65% C18:2n6, and 63.17% C18:3n3 fatty acids. For meat homogenates, fresh hand-deboned turkey thigh meat without skin was obtained from a local turkey processor, ground twice in a Hobart meat grinder5 through 8- and 3-mm plates, vacuum packaged (200 g each), and stored in a –20 C freezer until used. Cookedmeat homogenates were prepared after cooking the ground meat (100 g in a plastic bag) at 85 C for 30 min in a water bath to an internal temperature of 78 C. A 5-g meat sample was placed in a 50-mL test tube and homogenized with 15 mL of DDW by using a Brinkman Polytron6 for 15 s at speed 7 to 8. Iron from each of the various sources (0.1 mL) and 0.5 mL oil emulsion or meat homogenate were added to disposable test tubes (13 × 100 mm). The homogenates were mixed and then 0.1 to 0.4 mL DDW and prooxidant treatment were added. In ascorbate-containing homogenates, 0.1 mL ascorbate solution was added instead of DDW to give a total volume of 1 mL. Iron was added to control samples without addition of enzyme solution. containing 1 mL sample mixture were vortexed and incubated for 1 h in a 37 C water bath. The sample mixture was added with 1 mL of 11.3% TCA and 50 mL of 5% BSA solution to precipitate the oil emulsion. Subsequently, 0.8 mL of 10% ammonium acetate and 0.2 mL of ferroin color reagent were added, mixed, and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was read at 562 nm against a blank (2 mL distilled water + 0.8 mL of 10% ammonium acetate + 0.2 mL ferroin color reagent) after 5 min. For the release of iron from iron proteins, a 4-mL oil emulsion prepared as previously described, was mixed with an iron source (5 ppm iron equivalent in oil emulsion, final concentration) and treatment (none, ascorbate, KO2, H2O2, and XOD system) combinations. Samples were filtered through a Centricon membrane filter7 (cut-off size: 10,000 kDa), and the filtrate was used to determine the amount of free iron released from iron sources under the various treatment conditions. The filtration was accomplished by centrifuging the Centricon at 3,000 × g for 120 min. The filtrate and filtration residue (unfiltered) collected after the centrifugation were also used to determine their effects on lipid oxidation in oil and meat homogenates as described above as needed. Statistical Analysis Lipid Peroxidation Lipid peroxidation was determined by the method of Buege and Aust (1978). Test tubes containing 1 mL sample mixture, prepared as described above, were incubated for 1 h in a 37 C water bath. Immediately after incubation, 50 mL 7.2% BHA and 2 mL TBA/TCA solution were added. The mixture was vortexed and then incubated in a boiling water bath for 15 min to develop color. After color development, the samples were cooled in cold water for 10 min and then centrifuged for 15 min at 2,000 × g. The absorbance of the resulting supernatant solution was determined at 531 nm against a blank containing 1 mL DW and 2 mL TBA/TCA solution. The TBARS numbers were expressed as milligrams malonaldehyde (MDA) per liter of incubating homogenates. Nonheme Iron Determinations The ferrozine method of Carter (1971), modified for the use in meat samples (Ahn et al., 1993c), was used to analyze reduced iron and total iron when needed. To determine the content of ferrous iron in raw-meat homogenates, 0.5 mL meat homogenate, 0.1 to 0.4 mL treatment combinations (0.1 mL for each component) and 0.1 to 0.4 mL DDW were added to a disposable test tube (13 × 100 mm) to give a total volume of 1 mL. The test tubes 5Model 84185, Hobart Manufacturing Corp., Troy, OH 44859. 6Type PT 10/35, Brinkman Instruments Inc., Westbury, NY 11590-0207. 7Amicon Inc., Beverly, MA 01915. The experiment was designed primarily to determine the catalysis of lipid peroxidation in oil emulsion, and raw and cooked tissue homogenates under various reactive oxygen species. The data (four replications) for the meat homogenate and oil emulsion treatments were analyzed separately by SAS software (SAS Institute, 1986). Analyses of variance were conducted to test treatment effects within a meat homogenate or oil emulsion system. The treatments compared were control, H2O2, KO2, KO2 + H2O2, XOD, SOD, and SOD + XOD. These treatments were compared with the presence of Fe2+, Fe3+ + ascorbate, and no added iron; Hb, Hb + ascorbate, and no added Hb; and ferritin, ferritin + ascorbate, and no added ferritin. The Student-Newman-Keuls multiple range test was used to compare differences among mean values. Mean values and SEM are reported, and replications were used as the error terms for the calculations. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Ferrous Iron and Oxidation There were clear differences in the way ferrous iron catalyzed lipid oxidation in meat homogenates and oil emulsions (Table 1). In oil emulsions, ferrous iron had a strong prooxidant effect; however, the strong prooxidant effect of ferrous iron disappeared in the presence of .O2–, H2O2, or the XOD system (XOD + xanthine). The TBARS value of oil emulsion with XOD system was greater than those of .O2– and H2O2 but less than those of control, SOD, and SOD + XOD systems. This result contradicts the 351 PROOXIDANT EFFECTS OF IRON SOURCES IN DIFFERENT TESTING SYSTEMS TABLE 1. Effect of ferrous iron1 on the TBARS values of oil emulsion, and raw-meat and cooked-meat homogenates with added reactive oxygen species, SOD, or XOD systems2 Oil emulsion Raw-meat homogenate Treatment None Fe2+1 Fe2+ + asc. Control H2O2 KO2 KO2 + H2O2 XOD system SOD system SOD + XOD systems SEM 0.02b 0.01b 0.01b 0.05b 0.03b 0.16a 0.17a 0.00 2.82a 0.19d 0.29d 0.16d 0.51c 2.85a 1.20b 0.02 3.15a 1.30d 2.11c 1.16d 1.44d 2.82b 1.98c 0.03 a–eMeans Fe2+ None (mg MDA/L reaction 0.26ab 1.19bc 0.19bc 1.39a 0.29ab 1.27b 0.18bc 1.44a 0.15c 0.23d 0.36a 1.44a 0.11c 0.18d 0.01 0.01 Cooked-meat homogenate Fe2+ + asc. None Fe2+ Fe2+ + asc. mixture) 0.77c 1.18b 1.25b 2.01a 1.16b 0.67c 0.55d 0.01 0.89a 0.87a 0.83a 0.82a 0.58b 0.91a 0.63b 0.01 1.70b 0.69e 0.93d 0.63e 0.76e 1.95a 1.17c 0.01 3.94b 2.71d 3.51c 2.77d 2.70d 5.00a 4.15b 0.02 within a column with no common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05). n = 4. 1There was 5 ppm iron (89.5 mM); XOD system: 0.145 U XOD plus 2 mM xanthine; SOD system: 500 U catalase plus 50 U SOD/mL; KO , 100 ppm (1.4 2 mM); ascorbate, 100 ppm (0.57 mM); H2O2, 2 mM (final concentrations). 2TBARS = thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; SOD = superoxide dismutase; XOD = xanthine oxidase; MDA = malondialdehyde; H O = 2 2 hydrogen peroxide; KO2 = potassium superoxide, asc. = ascorbate. widely accepted superoxide-driven Fenton reaction, in which .OH is produced from .O2– and iron to initiate lipid peroxidation. This unexpected result, however, was caused by the oxidation of ferrous iron to ferric form by the .O2– (KO2) or H2O2 added in oil emulsion. Ahn and Kim (1997, unpublished data) observed that both .O2– and H2O2 oxidized ferrous iron to ferric form rapidly and the ferric form of iron had no reactivity with both .O2– and H2O2. There are no reducing agents that can reduce ferric iron to ferrous form present in the oil emulsion. Therefore, the production of .OH in oil emulsion with .O2– (KO2) or H2O2 lasted only for a short time, which limited the prooxidant effect of ferrous iron. The TBARS value of the oil emulsion with SOD system (SOD + catalase) was similar to that of the control, suggesting that the SOD system had no effect on the prooxidant effect of ferrous iron in oil emulsion. However, the addition of the SOD system in the presence of the XOD system increased the TBARS values of the oil emulsion. The prooxidant effect of catalase contributed to the high TBARS values of the oil emulsion with SOD system (data not shown), and the dismutation of .O2– (SOD) and degradation of H2O2 (catalase) should be responsible for the higher TBARS value in oil emulsion with SOD + XOD system than that with XOD system (Table 1). The addition of ascorbate in the oil emulsion containing ferrous iron significantly increased the TBARS values of the oil emulsion under all reactive oxygen species treatments, except the SOD system, which had little effect on the prooxidant effect of ferrous iron in oil emulsion with or without ascorbate. The added ascorbate reduced ferric iron to the ferrous form and maintained the high prooxidant effect of iron even in .O2–, H2O2, and XOD system treatments. The cycling of the valence of iron (ferrous iron ↔ ferric iron) in oil emulsion with ascorbate and XOD system produced .OH continuously and the oxidation of lipids continued while ascorbate was available. The prooxidant effects of ferrous iron in raw-meat homogenates were totally different from those in oil emulsion under various reactive oxygen conditions, and the influences of ascorbate, .O2–, or H2O2 were also dramatically different from those in oil emulsion. In rawmeat homogenates, only the samples containing the XOD system nullified the prooxidant effect of ferrous iron via the continuous production of .O2– and H2O2. The XOD system reduced the TBARS values of raw-meat homogenates more than that of the .O2–, H2O2, H2O2 plus .O2– or the SOD systems. The .O2– and H2O2 produced by the XOD system should have maintained the iron in ferric form. When ascorbate plus ferrous iron was added, the TBARS values of raw meat homogenates with H2O2, .O2–, .O2– + H2O2 or the XOD system were significantly higher than that of the control; however, the TBARS values of raw meat homogenates with the SOD system maintained the same or less than that of the control. The addition of ascorbate in raw-meat homogenates decreased the prooxidant effect of ferrous iron in the control, H2O2, and SOD systems, but increased that effect in .O2– + H2O2, and XOD systems. The large increase of TBARS values in raw meat homogenates with the XOD system can be explained by the continuous production of .O2– and H2O2 and the regeneration of ferrous iron by the added ascorbate. The decrease in TBARS values in meat homogenates with SOD system should be caused by the removal of .O2– and H2O2 by SOD and catalase. The prooxidant effects of ferrous iron (with and without ascorbate) in cooked-meat homogenates with various reactive oxygen species conditions were similar to those of oil emulsion. The .O2–-generating systems (XOD system and KO2) and their products (H2O2 and .O2–) reduced the TBARS values of cooked-meat homogenates by converting the active form of iron (ferrous) to an inactive form (ferric). The effect of ascorbate on the oxidation of oil emulsion, and raw and cooked meat homogenates were different. 352 AHN AND KIM TABLE 2. Effect of hemoglobin (Hb)1 on the TBARS values of oil emulsion, and raw-meat and cooked-meat homogenates with added reactive oxygen species, SOD, or XOD systems2 Oil emulsion Raw-meat homogenate None Hb1 Hb + asc. None Hb + asc. None Hb1 Hb + asc. Control H2O2 KO2 KO2 + H2O2 XOD system SOD system SOD + XOD systems SEM 0.02b 0.01b 0.01b 0.05b 0.03b 0.16a 0.17a 0.00 3.15b 2.79c 3.65a 2.07e 2.37d 3.54a 2.40d 0.02 3.24a 2.66b 3.08a 2.78b 2.17c 3.28a 2.14c 0.03 (mg MDA/L reaction mixture) 0.26ab 0.07b 0.14 0.19bc 0.08b 0.14 0.29a 0.09b 0.14 0.18bc 0.09b 0.13 0.15c 0.20a 0.14 0.36a 0.08b 0.12 0.11c 0.10b 0.13 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.89a 0.87a 0.83a 0.82a 0.58b 0.91a 0.63b 0.01 1.09c 1.72a 1.78a 1.69a 0.71e 1.27b 0.87d 0.01 1.95a 2.02a 2.13a 1.89a 1.19b 1.87a 1.36b 0.02 a–eMeans Hb1 Cooked-meat homogenate Treatment within a column with no common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05). n = 4. 1Hb: 5 ppm iron (89.5 mM) equivalent (1.56 mg/mL, final). XOD system: 0.145 U XOD plus xanthine (2 mM)/mL; SOD system: 500 U catalase plus 50 U SOD/mL; KO2. 100 ppm (1.4 mM); ascorbate, 100 ppm (0.57 mM); H2O2, 2 mM (final concentrations). 2TBARS = thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; SOD = superoxide dismutase; XOD = xanthine oxidase; MDA = malondialdehyde; H O = 2 2 hydrogen peroxide; KO2 = potassium superoxide; asc = ascorbate. Addition of ascorbate increased the prooxidant effect of ferrous iron in oil emulsion and cooked-meat homogenates, especially with superoxide-generating systems and reactive oxygen species. However, the effect of added ascorbate reduced the TBARS values of raw meat homogenates in control, H2O2, and SOD system, but increased in the KO2 plus H2O2, XOD system and SOD + XOD systems. This result indicated that raw meat homogenate has strong reducing power, which was different from that of the added ascorbate. The reducing power in raw meat homogenates could maintain most of the added iron to raw meat homogenates in the ferrous form even under .O2–, H2O2, or both. A relatively low ascorbate content in meat homogenates (approximately 6 ppm) suggests that only a small part of the reducing power of the raw meat homogenate could originate from ascorbate. Ghiselli et al. (1995) also reported that there are many antioxidant compounds present in plasma, and ascorbate plus thiol groups are only about 25% of the total antioxidant capability. Oxygen plays a more critical role in the oxidation of lipids in cooked-meat than it does in the oxidation of lipids in raw meat (Ahn et al., 1993d). Therefore, the involvement of certain heat-labile substances, possibly reducing enzymes or organelles (e.g., mitochondria) that can maintain reducing conditions by consuming oxygen in raw-meat homogenates, could be responsible for the differences in the prooxidant mechanisms of iron between oil emulsion/cooked-meat homogenates and raw-meat homogenates. Hb and Oxidation The mechanism and the prooxidant effect of Hb in lipid peroxidation of oil emulsions are quite different from those of meat homogenates, especially raw-meat homogenates. As shown in Table 2, Hb had very strong prooxidant effects in oil emulsions regardless of the presence or absence of ascorbate and reactive oxygen species. As far as the prooxidant effect of Hb in oil emulsion was concerned, heme iron did not appear to have an effect; however, the presence of H2O2 or XOD system reduced the prooxidant effect of Hb in oil emulsions. In raw meat homogenates, Hb was not a prooxidant under all ascorbate and reactive oxygen species conditions. In cooked-meat homogenates, however, Hb had some catalytic effects on lipid oxidation. The catalytic effects of Hb in cooked-meat homogenates was increased when .O2–, H2O2, or .O2– + H2O2 were present. The TBARS values of cooked-meat homogenates with ascorbate were higher than those without ascorbate, indicating that free ionic iron was also involved in the oxidation of cooked-meat homogenates. The reason for the dramatic difference in the prooxidant effects of hemoglobin in oil emulsions, and raw and cooked-meat homogenates is not clear; however, substances other than reducing agents, such as ascorbate, are involved. Johns et al. (1989) found a powerful prooxidant effect of heme pigments in exhaustively washed muscle fibers. Their samples had only membrane components (mainly phospholipids) and myofibrillar proteins and connective tissues due to washing off all the water-soluble components were rinsed away, whereas the oil emulsion used in our study contained only lipids. Because myofibrillar proteins-only have no known effect on the oxidation of lipids, the conditions of washed muscle fibers are basically the same as those of the oil-only emulsion system. The reactions of iron sources in exhaustively washed muscle fibers, thus, became very similar to those of oil emulsion in this study. These results (Johns et al., 1989 and Table 2) indicated that the most of the components that prevent heme pigments from being prooxidant would be watersoluble, and heat-labile cytoplasmic substances. Because of those unknown substances the rate of lipid oxidation in raw-meat with Hb is very slow, and the oxidation mechanisms of raw-meat are different from those of cooked-meat and oil emulsion systems. However, the PROOXIDANT EFFECTS OF IRON SOURCES IN DIFFERENT TESTING SYSTEMS 353 TABLE 3. Effect of ferritin on the TBARS values of oil emulsions and raw-meat homogenates with added reactive oxygen species, SOD, or XOD systems1,2 Oil-emulsion Treatment None Ferritin2 Control H2O2 KO2 KO2 + H2O2 XOD system SOD system SOD + XOD systems SEM 0.02b 0.01b 0.01b 0.05b 0.03b 0.16a 0.17a 0.00 0.05c 0.04c 0.05c 0.06c 0.05c 1.26a 0.65b 0.01 Raw-meat homogenate Ferritin + asc. None Ferritin (mg MDA/L reaction mixture) 2.14b 0.26 0.11b 0.08e 0.19 0.19a 0.08e 0.29 0.22a 0.10e 0.18 0.11b 0.75d 0.15 0.15ab 3.24a 0.36 0.09b 1.67c 0.11 0.09b 0.02 0.01 0.00 Ferritin + asc. 0.10 0.14 0.16 0.20 0.13 0.12 0.11 0.00 a–eMeans within a column with no common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05). n = 4. homogenate was not tested. 2TBARS = thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; SOD = superoxide dismutase; XOD = xanthine oxidase; MDA = malondialdehyde; H2O2 = hydrogen peroxide; KO2 = potassium superoxide, asc = ascorbate. 3Ferritin: 5 ppm iron (89.5 mM) equivalent (25 mg/mL, final); XOD system: 0.145 U XOD plus xanthine (2 mM)/ mL; SOD system: 500 U catalase plus 50 U SOD/mL; KO2, 100 ppm (1.4 mM); ascorbate, 100 ppm (0.57 mM); H2O2, 2 mM (final concentrations). 1Cooked-meat SOD, and SOD + XOD systems. The presence of .O2–, H2O2, .O2– + H2O2, or XOD in the oil emulsion significantly reduced the TBARS values of the samples containing both ascorbate and ferritin, indicating that not only release of ferritin iron but also changes in the status of free iron are important factors in the prooxidant capability of ferritin. The ferritin had no prooxidant effect, and the presence of ascorbate or reactive oxygen species and XOD/SOD systems also had no influence on the catalytic effect of ferritin in raw-meat homogenates (Table 3). mechanisms of these heat-labile cytoplasmic components can not be explained at this point. Ferritin and Oxidation Ferritin had no prooxidant effect in the oil emulsion with control, .O2–, H2O2, .O2– + H2O2, or XOD but had significant prooxidant effects when SOD was present (Table 3). The high TBARS values in oil emulsion samples with ferritin, however, were not caused by ferritin but by catalase, an enzyme in the SOD system. Obviously, catalase also accounts for part of the MDA produced in the SOD system for both ferrous iron and Hb treatments (Tables 1 and 2). Catalase-stimulated MDA formation was also observed in phospholipid liposomes (Thomas et al., 1985). When ascorbate was added to the ferritin samples, it increased the TBARS values of oil emulsion with control, Amount and Status of Free Iron Tables 2 and 4 support the view that Hb itself (not iron released from Hb) is a strong prooxidant in oil emulsions, and the status of heme iron and the release of free iron from Hb by .O2–, H2O2, and the XOD system were less important on the prooxidant effect of Hb in oil emulsions. TABLE 4. Effect of ascorbate, superoxide, H2O2, and the XOD system on the release of iron from iron proteins in oil emulsion1,2 Hemoglobin Treatment Total Fe Control Ascorbate KO2 H2O2 XOD + xanthine SEM 0.30c 0.57b 0.28c 0.54b 1.22a 0.01 a–cMeans Ferritin Fe2+ Total Fe (mg Fe/mL reaction mixture) 0.05b 0.30c 0.46a 0.51b 0.05b 0.23c 0.02b 0.54b 0.06b 0.64a 0.00 0.01 FE2+ 0.04b 0.41a 0.01b 0.00b 0.01b 0.00b within a column with no common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05). n = 4. ppm Fe equivalent (89.5 mM) for iron proteins (Hb 15.6 mg/mL, ferritin 25 mg/mL); Oil emulsion was filtered through a membrane filter (cut-off size: 10 kd) by centrifugation and the filtrate was used for iron analysis. XOD, 0.145 U/mL; KO2, 2 mM; ascorbate, 2 mM; xanthine, 2 mM, H2O2, 2 mM (final conc.) were used. 2H O = hydrogen peroxide; XOD = xanthine oxidase; KO = potassium superoxide. 2 2 2 15 354 AHN AND KIM TABLE 5. Effect of H2O2, XOD, and SOD systems on the content of ferrous iron1 in raw-meat homogenates2 Treatment Fe2+ None H2O2 SOD + catalase XOD + xanthine SEM 3.33c 3.23c 3.60b 5.61a 0.02 Fe2+ = ascorbate Fe2+ + KO2 SEM (ppm Fe in reaction mixture) 5.16c 2.66c 0.04 5.29c 2.80c 0.03 5.76b 3.27b 0.04 7.21a 4.64a 0.03 0.05 0.03 a–cMeans within a column with no common superscript differ significantly (P < 0.05). n = 4. 15 ppm ferrous iron (89.5 mM); XOD, 0.29 U/mL; catalase, 1,000 U/ mL; SOD, 200 U/mL; H2O2, 2 mM (final concentrations) were used. 2H O = hydrogen peroxide; XOD = xanthine oxidase; SOD = 2 2 superoxide dismutase; KO2 = potassium superoxide. Ascorbate, H2O2, and XOD system mobilized more iron from ferritin and Hb than those of control and KO2 treatments, only ascorbate kept the released iron in the ferrous state and catalyzed the oxidation of oil emulsions. Less than 10% of iron from the iron proteins was released under the tested conditions, except for the XOD system, and almost all of the free iron in oil emulsions without reducing agents was in the inactive (ferric) form. Table 5 shows that SOD and XOD systems had significant effects on the content of analyzable ferrous iron in meat homogenates. The content of ferrous iron in meat homogenates with the XOD system was approximately 2 ppm greater than those of control, H2O2, and SOD systems. The addition of ascorbate significantly increased but .O2– reduced the amount of ferrous iron in meat homogenates. Although the amount of ferrous iron and TBARS values correlated well in the oil emulsion and cooked-meat homogenates (Table 1), the amounts of ferrous iron in Table 5 did not agree well with the TBARS values of raw-meat homogenates in Table 1. This lack of agreement indicates that the prooxidant effects and mechanisms of iron, ferritin, and Hb in raw-meat homogenates are different from those in oil emulsions and cooked-meat homogenates. The results shown in this study underscore a few important points: 1) ferrous iron and hemoglobin had strong prooxidant effects in oil emulsions, 2) the status of heme iron and the released iron from Hb had minor effects on the catalytic effect of Hb in oil emulsion, 3) Hb had no catalytic effect on the oxidation of raw-meat homogenates under any circumstances, and 4) the reaction of Hb with H2O2 did not produce active Hb that can catalyze lipid oxidation in raw-meat homogenates. We conclude that the prooxidant effects and the mechanisms of ionic iron, ferritin, and Hb in raw-meat homogenates are different from those in oil emulsion and cooked-meat homogenates, and the differences were caused by heat-labile components such as reducing enzymes related to the balance of redox potentials in rawmeat homogenates. The presence of ascorbate, H2O2, and XOD system can increase the release of iron from iron proteins (Hb and ferritin). The status of free iron was more important than the amount of free iron on the oxidation in oil emulsion. Ferrous iron was the most important prooxidant among all iron sources, and heme pigments and ferritin had no catalytic effect on the oxidation of rawmeat homogenates during storage. REFERENCES Ahn, D. U., F. H. Wolfe, and J. S. Sim, 1993a. The effect of metal chelators, enzyme systems, and hydroxyl radical scavengers on the lipid peroxidation of raw turkey meat. Poultry Sci. 72: 1972–1980. Ahn, D. U., F. H. Wolfe, and J. S. Sim, 1993b. The effect of free and bound iron on lipid peroxidation in turkey meat. Poultry Sci. 72:209–215. Ahn, D. U., F. H. Wolfe, and J. S. Sim, 1993c. Three methods for determining nonheme iron in turkey meat. J. Food Sci. 58: 288–291. Ahn, D. U., A. Ajuyah, F. H. Wolfe, and J. S. Sim, 1993d. Oxygen availability effects in prooxidant catalyzed lipid oxidation of cooked turkey patties. J. Food Sci. 58:278–282. Baldwin, D. A., E. R. Jenny, and P. Aisen, 1984. The effect of human serum transferrin and milk lactoferrin on hydroxyl radical formation from superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. J. Biol. Chem. 259:13391–13394. Biemond, P., A.J.G. Swaak, C. M. Beindorf, and J. F. Koster, 1986. Superoxide-dependent and -independent mechanisms of iron mobilization from ferritin by xanthine oxidase. Implications for oxygen-free-radical-induced tissue destruction during ischemia and inflammation. Biochem. J. 239:169–173. Buege, J. A., and S. D. Aust, 1978. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 52:302. Carlin, G., and R. Djursater, 1984. Xanthine oxidase-induced depolymerization of hyaluronic acid in the presence of ferritin. FEBS Lett. 177:27–30. Carter, P., 1971. Spectrophotometric determination of serum iron at the submicrogram level with a new reagent (ferrozine). Anal. Biochem. 40:450–458. Chen, C. C., A. M. Pearson, J. I. Gray, M. H. Fooladi, and P. K. Ku, 1984. Some factors influencing the non-heme iron content of meat and its implication in oxidation. J. Food Sci. 49: 581–584. Decker, E. A., and B. Welch, 1990. Role of ferritin as a lipid oxidation catalyst in muscle food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 38: 674–677. Ghiselli, A., M. Serafini, G. Maiani, E. Azzini, and A. Ferro-Luzzi, 1995. A fluorescence-based method for measuring total plasma antioxidant capability. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 18: 29–36. Gutteridge, J.M.C., 1986. Iron promoters of the Fenton reaction and lipid peroxidation can be released from hemoglobin by peroxides. Fed. Euro. Biol. Soc. 201:291–295. Halliwell, B., and J.M.C. Gutteridge, 1986. Oxygen free radicals and iron in relation to biology and medicine: some problems and concepts. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 246:501–514. Halliwell, B., and J.M.C. Gutteridge, 1990. Role of free radicals and catalytic metal ions in human diseases: an overview. Methods Enzymol. 186:1–85. Hidalgo, F. J., R. Zamora, and A. L. Tappel, 1990. Oxidantinduced hemeprotein degradation in rat tissue slices: effect of bromotrichloromethane, antioxidants and chelators. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1037:313–320. PROOXIDANT EFFECTS OF IRON SOURCES IN DIFFERENT TESTING SYSTEMS Hirano, J., and H. S. Olcott, 1971. Effect of heme compounds in lipid oxidation. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 48:523–524. Johns, A. M., L. H. Birkinshaw, and D. A. Ledward, 1989. Catalysts of lipid oxidation in meat products. Meat Sci. 25: 209–220. Kanner, J., and S. Harel, 1985. Initiation of lipid peroxidation by activated metmyoglobin and methemoglobin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 237:314–321. Kanner, J., B. Hazan, and L. Doll, 1988. Catalytic “free” iron ions in muscle foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 36:412–415. Kanner, J., S. Harel, and R. Jaffe, 1991. Lipid peroxidation of muscle food as affected by NaCl. J. Agric. Food Chem. 39: 1017–1021. Kaschnitz, R. M., and Y. Hatefi, 1975. Lipid oxidation in biological membranes. Electron transfer proteins as initiators of lipid oxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 171: 292–304. 355 Love, J. D., and A. M. Pearson, 1974. Metmyoglobin and nonheme iron as prooxidants in cooked-meat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 22:1032–1034. Miller, D. M., G. R. Buettner, and S. D. Aust, 1990. Transition metals as catalysts of autoxidation reactions. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 8:95–108. SAS Institute, 1986. SAS User’s Guide. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC. Sato, K., and G. R. Hegarty, 1971. Warmed-over flavor in cookedmeats. J. Food Sci. 36:1098–1102. Shen, X., J. Tian, X. Li, and Y. Chen, 1992. Formation of the excited ferryl species following Fenton reaction. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 13:585–592. Thomas, C. E., L. A. Morehouse, and S. D. Aust, 1985. Ferritin and superoxide-dependent lipid peroxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 260:3275–3280.