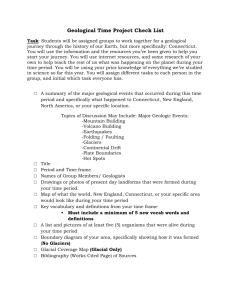

RESOURCES

advertisement