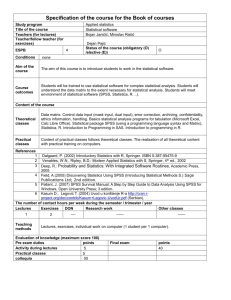

A the Instruction of Survey Data Analysis

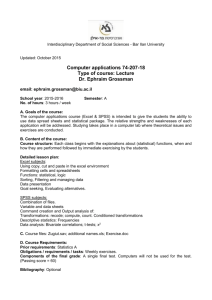

advertisement