Adaptive Reuse and Revitalization of SEP 2012j

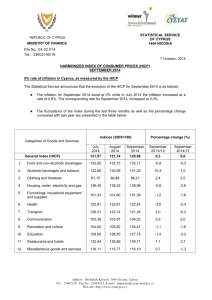

advertisement