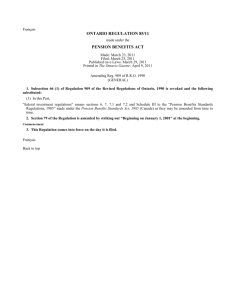

(1979)

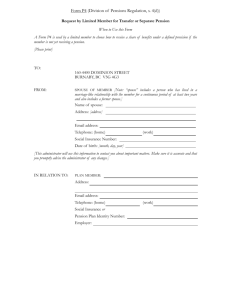

advertisement