(1931) .

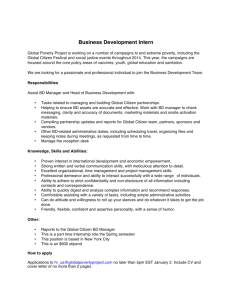

advertisement