A FOR OLDER WOMEN BLAND OUZTS B.

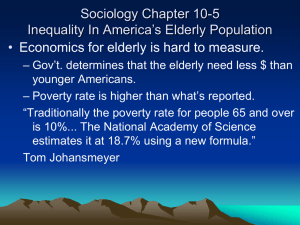

advertisement