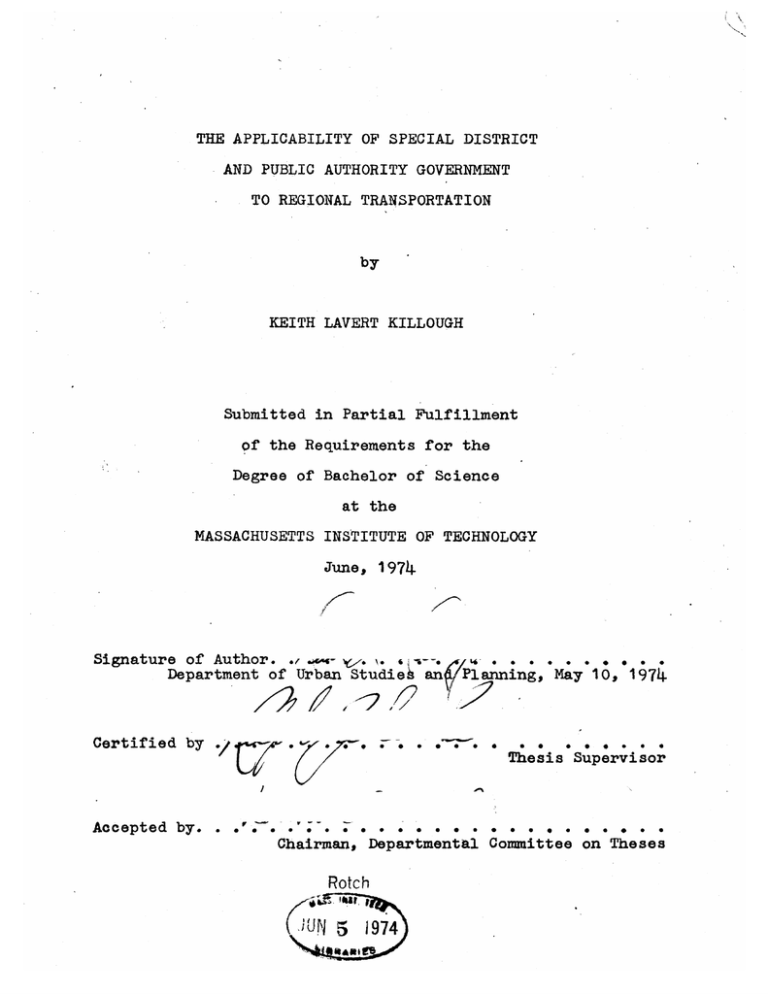

THE APPLICABILITY OF SPECIAL DISTRICT TO AND

advertisement