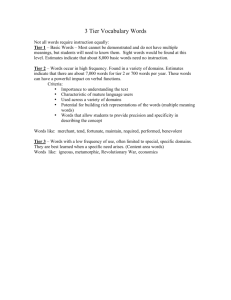

A Third Way of Managing and Incenting a Growing

advertisement

A Third Way of Managing and Incenting a Growing Electric Power Supply and Delivery System Stephen T. Lee Technical Executive Power Delivery & Markets Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) Abstract — Regulatory changes in North America since FERC Order 888 in 1997 which required open access to the naturally monopolistic transmission grid have been accompanied by market failures and reliability problems. One year after the major blackout on August 14, 2003, not much, if any, has been implemented in the regulatory and financial areas to fundamentally induce more transmission capacity to be built. This paper will propose a third way of regulatory and financial structures and incentives which may fix this problem, seeking a balance between the traditional regulated and vertical utility structure and the idealized power market designs which have viewed the transmission grid as a monopoly requiring regulation. This paper proposes a new way of combining regulatory oversight with market-based incentives for transforming the transmission companies into a business which will provide public benefit solutions for the transmission investment problem. A new area of research is proposed. It is to investigate a new economic system, a third way, which overcomes the deficiencies of capitalism/free market and socialism/central planning. This concept is called Unity in Diversity-ism or UDI-ism. An example of a long distance transmission project is used to illustrate the concept. The transmission grid is a natural monopoly and therefore a transmission market operation will not work. • Transmission access is not a commodity whose value can be market-based. • Transmission charges based on actual usages are too difficult to implement. • New transmission lines crossing multiple governmental boundaries (provinces, states or nations) are impossible to get approved because of local interests and environmental objections If we accept the conventional wisdom, then transmission business will remain not a good business. Risk of investing in long transmission lines crossing multiple state boundaries will remain higher than the potential return on investment. A higher regulated rate of return may not be sufficient. In challenging these premises, a third way of managing and inducing the growth and efficient operation of the transmission grid is developed, as opposed to the vertically-integrated fully regulated way and the current-day typical power market approaches. It builds upon the work done in three areas: the concept of the Community Activity Room [1], the concept of the Virtual RTO (regional transmission organization) [2, 3] and the concept of the Automatic Transmission Toll Collection System [4, 5]. These three concepts enable financial transactions to be done using computers and communication. It will ensure that the providers of the market value of transmission access receive their fair payments. In addition, the concept of monetizing all cost and benefit elements, including all externalities, into a complete economic framework will be explored. Keywords – Transnational Networks, Power System Planning Under Market Conditions, Power Market Restructuring, Economic Analysis I. • INTRODUCTION Regulatory changes in North America since FERC Order 888 in 1997 which required open access to the naturally monopolistic transmission grid have been accompanied by market failures and reliability problems. One year after the major blackout on August 14, 2003, not much, if any, has been implemented in the regulatory and financial areas to fundamentally induce more transmission capacity to be built. This paper proposes a different combination of regulatory, financial and ownership structures, and incentives which may fix this problem. The proposed structure seeks a balance between the traditional regulated and vertical utility structure and the typical power market designs which have viewed the transmission grid as a natural monopoly requiring regulation and open access. This framework may provide the means for overcoming local objections for building transmission lines that cross multiple state boundaries. It may also provide the proper financial incentives for solving some of the seams problems related to Transmission Loading Relief between ISO/RTO and non-LMP markets. Following are premises that are challenged in this paper: The vision of this paper is to develop a framework for achieving unity in diversity, wherein unity means achieving common good and diversity means maximizing personal 1 interests. The objective of this framework is to provide a public good solution for all parties involved, generators, transmission companies, distribution companies, customers, non-customers and the states. It must be fair for all parties and it must balance reliability, economics, the environment, local interests, national interests, and perhaps even global interests. II. It can be a win-win-win for all three parties In LMP market, if bottleneck is not removed, this is the price customers pay. Demand Need to create incentive to build transmission by letting the T&D share in this value Price customers are willing to pay Price Supply Congestion Revenue: T&D should receive a part of this $ value WHY TRANSMISSION ACCESS MAY USE MARKETBASED PRICES Price generator is willing to sell When a power market uses supply and demand curves to set market prices, all parties involved in completing the transaction between the seller and the buyer are necessary for the transaction to succeed. These parties are: the generator, the broker (if any), the power exchange or the regional operator, the transmission companies, the distribution company, and the end-use customer. With transmission bottleneck Under regulation, if bottleneck is not removed, this is the price customers get. Perfect market and no transmission bottleneck Quantity of Electricity Figure 1 – Example of the Supply and Demand Curves for a Power Market with a Transmission Bottleneck In challenging conventional wisdom, one could ask why the transmission and distribution companies should only be reimbursed at cost plus regulated return, while the generator and the broker (if any) receive the excess between the market price and the cost of production. If the transmission or distribution companies open the circuit breakers disconnecting the generator, or disconnecting the customer, the supply chain is broken and the transaction cannot be completed. As they are indispensable to the transaction, it seems that they deserve to share in the difference between the market value and the cost of production. economically justifiable. If the incentive and regulatory system is set up right, it can result in a win-win-win-win situation for the sellers, the T&D companies, the customers and the public. III. UNITY IN DIVERSITY (UDI-ISM) One of the deficiencies of a pure market system is the tendency towards a boom and bust cycle. Examples of that include the U.S. real-estate bubble in the 1980s which led to the collapse of the U.S. savings and loan associations, costing the American taxpayer more than $100 billion [6]. Another example is the telecommunication bubble which went from boom to bust in just nine years, from 1992 to 2001. Even the power market in California had experienced a cyclic phenomenon where the power shortage in the summer of 2000 led to a burst of power plant construction which subsequently slowed because of the ensuing drop in electricity prices. Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel economist, believes that his research on the consequences of imperfect and asymmetric information (where different individuals know different things) has shown that one of the reasons that the “invisible hand” economists associate with Adam Smith may be invisible is that it is simply not there. They are not allowed to do so currently, because of the concern about market power abuse. However, they provide valuable and indispensable services, as much as the generator, or a broker. There are no intrinsic reasons other the concern about market power abuse to argue that they do not deserve to share in the market value. So, if more regulatory oversight can prevent market power abuse, why not share the excess of the market value above cost among all parties involved? If this is done, then the transmission and distribution companies will become active market players and bring innovation to bear on solving the transmission planning and operation problems. For example, if the market system is a regional market operator, and an existing transmission bottleneck causes the market price to clear at a higher price than the ideal situation without the bottleneck, there is a difference between the demand curve’s price and the supply curve’s price, as shown in Figure 1. In the book “20:21 Vision”, Bill Emmott, the Editor in Chief of The Economist, noted the failures of capitalistic markets to address environmental problems and their undesirable effects of increasing the income disparity between the rich and the poor within a country and between the rich nations and the poor nations [7]. In Figure 1, the congestion revenue represents the difference between the price that the customers are willing to pay and the price that the generator is willing to sell. It seems reasonable that T&D companies should receive a part of that value. If they do receive some revenue, the revenue they receive should ideally be directed towards resolving the congestion, e.g., by building more transmission capacity. This way, the overall economic efficiency of the power market is enhanced. The key challenge is to create a financial incentive system whereby the bottleneck will be removed, if In human history, two economic systems have been put to practice. Central planning (as implemented in Communism) and capitalistic market system engaged in a global competition during the twentieth century. Central planning proved to be stable but not conducive to innovation and economic efficiency. In comparison, the capitalistic market system has flourished. However, there are deficiencies in the capitalistic market system as well. Many economists are considering various alternatives and call them “The Third Way.” 2 A. Basic Principles of UDI-ism The concept of Unity in Diversity (abbreviated to UDI-ism) as proposed by this author is to preserve the creativity and energy of capitalism and the free market wherein maximizing self interests is the key ingredient for diversity and innovation. At the same time, by aligning the diverse self interests more in line with public interest, unity is achieved by channeling that diversity into achieving both public and personal benefits. It will modify the tendency of a market system for being shortsighted in maximizing short-term profits. included in Tier 2 costs are explicitly considered in the decisions of the enterprises. The result would be solutions that are optimal from the total cost standpoint. 3) How Tier 2 Prices Are Determined Ideally, Tier 2 prices should be based on a market-like system. At the bottom is the cost, just like the production of an orange has a cost, consisting of the allocated costs of the grower, and the direct material and labor costs of producing and harvesting the orange, etc. A tree in the forest has a cost even though little or no money was spent by anyone on it. It is only free because it had used free Tier 2 assets to become what it is. A tree planted by the city on the street is not free. There are direct expenses incurred by the city to buy the sapling, plant it, irrigate it, prune it and maintain its health. 1) Tier 2 Assets and Prices UDI-ism introduces the key concept of a social asset (or Tier 2 asset), and the associated concepts of Tier 2 prices (or Tier 2 costs and Tier 2 benefits.) By internalizing these social costs into the economic and investment decisions of a firm, a government or the consumers, it is postulated that the overall economic efficiency of the entire system including all social costs will be improved. This will overcome the deficiency of many economic analyses wherein externalities are assumed to be cost-free to the decision making. Air is not free. Polluted air creates adverse health impacts on the residents (and vegetation and wild life also), which result in medical costs and the shortening of human lives, which in turn has economic effects. Water is not free. Its availability is often limited. Limited resources carry economic values, quantifiable by shadow prices or opportunity costs. Contaminated water, like polluted air, also creates adverse health impacts and therefore also has other cost effects. The idea is to quantify and perhaps even monetize these externalities, e.g., environmental costs, health costs, and other social costs such as unemployment benefits and retirement benefits. To monetize means to engage in real currency transactions. Products which have these social impacts will be shown to have a Tier 2 cost component in monetary terms. a) Scientific Studies Objective scientific studies can be conducted to quantify these cost effects. It will obviously take time for such quantification methodologies to be developed and analysis to be done. In time, these data will become more available. Including externalities into economic and financial decisions is one key principle of UDI-ism. Monetizing these externalities is significantly different from using laws to enforce regulatory limits on Tier 2 impacts. It turns a passive or combative attitude towards Tier 2 impacts into an enterprising search for innovative and profitable ways to consider Tier 2 impacts in business or governmental decisions. b) Polling Polling is another approach for determining Tier 2 prices. By conducting regular polls of the residents about the monetary value of different degrees of clean air or clean water, for example, without a controversial project approval currently at stake, unbiased values of Tier 2 assets could be obtained through scientific polls. Research is needed to develop methodologies for inferring Tier 2 values by making relative comparisons between two Tier 2 assets and looking for an indifference curve. 2) Tier 2 Ownerships and Rights Another key concept is that air, water, land, natural resources, wild life, personal health, historical and archaeological assets, etc., are assets that belong to the states and their residents. In other words, they form a Tier 2 class of assets. When enterprises use these assets or have adverse or beneficiary impacts on them, they are making use of these Tier 2 assets. If this principle is accepted, the issue of ownership of enterprises or their plants should be re-examined. As a consequence, the governance and the decision making process of the enterprises should also be re-examined in light of the Tier 2 assets being used or impacted. c) Trading In cases where trading for Tier 2 assets or rights is done through some market mechanism, e.g., air emissions, these prices may be used, with care. Prices due to the supply and demand for emission rights reflect the economic value of using those limited rights. They do not reflect the economic value of clean air to the public. In short, the states and the residents deserve certain amount of control of the enterprises and perhaps deserve to share in the costs and profits of the enterprises. d) Negotiation Until the methods listed above are viable, a practical approach to determine Tier 2 prices is by negotiation among the parties involved. Subjective factors are involved but the result will reflect a balancing of the willingness of the involved parties. If Tier 2 costs are monetized into product prices, then there will be a Tier 2 class of revenues and costs to be accounted for. The decision criteria of an enterprise would be to maximize the total profit, which would equal (revenue – Tier 1 costs – Tier 2 costs). With this new objective function, externalities that are 3 B. How UDI-ism May Reduce Capitalistic Market’s Deficiencies UDI-ism will modify the behavior of consumers, businesses and governments, by explicitly including Tier 2 considerations and by providing direct financial incentives that align selfish interests more closely with public benefits. Because Tier 2 considerations include long term costs and long term solutions, decisions will be less short-sighted and therefore less prone to the boom and bust cycles inherent in market systems. that are adjustable to UDI-ism principles may be used to modify business behavior. Tax credits based on performance measures, e.g., average gas mileage or air emissions of car fleet, may be used as direct financial incentives. Certain externalities to current business decisions can be partially internalized. An example is the cost of unemployment benefits. Firms that lay off employees in a business downturn are shifting their labor costs to the government. Firms that outsource labor requirements to foreign countries are also making the government bear the costs of unemployment and retraining. By excluding these costs in their decisions, it is likely that the decision is not optimal from the public interest viewpoint. One way to internalize these considerations is to debit a social account of the firm for part of the costs of the unemployment benefits. a) Monetized Tier 2 Prices Provide Direct Incentives If consumer products such as a hamburger or a cigarette include a Tier 2 price (whether it is a label designed for consumer awareness or actually monetized into the total purchase price) which reflects the social and health costs of the products, consumers will buy fewer of the expensive products and buy more of the cheaper products. Individuals could also have social accounts that give credits for Tier 2 contributions to society. For example, doing volunteer social work would earn credits in the social account. These credits would be translated into retirement benefits or medical benefits. Businesses will make better products, e.g., healthier hamburgers and cigarettes, or more delicious and healthy fast food. Innovative businesses will succeed and consumers are also better off. If environmental and health impacts due to different types of power plants are explicitly priced in the cost of electricity produced, then green energy will get a fair price treatment in a competitive electricity market. New and cleaner power plants such as fuel cells will also overcome the initial market barrier sooner and gain their truly economic market shares. Society will also be better off. IV. EXAMPLE OF A LONG TRANSMISSION LINE Coming back to the power system problem, we will apply the concept of UDI-ism to the construction of a long transmission line crossing three states, from State A, through State B, to State C. Customers in State B will use only 5% of the line and therefore should pay based on the low usage. Further, for this example, we assume that the Tier 2 impacts on State B are highest among the three States. If air pollution effects of health costs are included as a Tier 2 price in the cost of gasoline, instead of a fixed and nonmarket-based gasoline tax, consumers will modify driving habits and buy cars that are less polluting. Revenue from the Tier 2 price will go to the government just like the gasoline tax and may be used to provide financial incentives for inducing manufactures to make cleaner cars and for rewarding consumers who buy these cars. The capitalized Tier 2 costs (in million $) in the three States are assumed to be quantitatively assessed and agreed among all parties with some scientific method and polling of the people. They are shown in Table 1. Note that economic benefits from construction in the States are treated as Tier 2 benefits. Tier 2 Land use Vegetation effect Wild life effect Human health effect Aesthetics Water use Air quality Cultural or historical Subtotal Economic benefit from construction Net Tier 2 Cost % Share Car manufacturers may earn Tier 2 incentive payments from the government by making and selling cleaner cars, and improving the average gas mileage of their entire fleet, even though their Tier 1 costs may be higher. Car drivers, who pay higher gasoline prices but drive cleaner cars with better gas mileage, may receive tax credits. Tier 2 revenues can be used by the government to ensure fairness and to reward desirable consumer and business behavior. Tier 2 costs, if monetized, will directly affect consumer and business decisions. b) Other Means to Incent Tier 2 Considerations Before Tier 2 costs are monetized, it is possible to introduce Tier 2 considerations as financial incentives into consumer and business behavior by using other means such as taxation or social accounts. Tier 2 price stickers have already been mentioned as a way to influence consumer behavior. Tax rates State A 5 2 1 5 3 0 0 2 18 State B 10 5 5 2 5 1 0 5 33 State C 5 1 0 10 7 0 0 3 26 Total 20 8 6 17 15 1 0 10 77 10 8 17.0% 10 23 48.9% 10 16 34.0% 30 47 100.0% Table 1 – Example of the Tier 2 Costs for a Long Transmission Line From the net Tier 2 costs, the percentage share of each State based on Tier 2 cost is also shown in Table 1. Next, it is assumed that the Transmission Company is allowed to earn a 15% guaranteed rate of return plus a market 4 adder based on some kind of transmission toll collection [3, 4]. For the States and the residents to recover their Tier 2 investments, we assume a social discount rate of 5%. With a project life of 40 years, the annual capital recovery rates are 15.1% and 5.8% respectively, as shown in Table 2. State's Net Costs State A State B State C Total It is then assumed that the annual market value adder amounts to $5 million, and that the customers in State A, State B, and State C, use 35%, 5% and 60% of the line each year. The amounts customers in each state pay to the transmission company are then shown in Table 2. Notice that both Tier 1 and Tier 2 costs are paid by the customers in each State according to their usages of the line. It is assumed that the Transmission Company collects both Tier 1 and Tier 2 revenues and then send Tier 2 payments to each State. Transmission Costs 100 47 147 Tier 1 Tier 2 UDI Total Customer Costs State A State B State C Total Annual Charge 15.06 2.74 17.80 Market Value Adder 5.00 5.00 Customer Cost 7.98 1.14 13.68 22.80 State's Market State's Tier Revenue 2 Revenue 0.27 0.47 0.78 1.34 0.54 0.93 1.60 2.74 State's Net Cost Total to State & Revenue Customer 0.74 7.24 2.12 (0.98) 1.48 12.20 4.34 18.46 Table 4 – Example of Net Costs or Benefits to the States Finally, Table 4 shows the net costs and benefits to the customers and the States, showing that the method is fair and provides incentives for State B to allow the line to be built. It would seem that UDI-ism, when applied to this long distance transmission project, offers the following advantages: Total 20.06 2.74 22.80 % Usage Tier 1 Cost Tier 2 Cost Total Cost 35 7.02 0.96 7.98 5 1.00 0.14 1.14 60 12.03 1.64 13.68 100 20.06 2.74 22.80 • A negotiation framework for incorporating local concerns into a fair mechanism for the allocation of costs and benefits. The residents in each State take part ownership of the project. • A market mechanism for transmission companies to share in the market value of a transmission project • A full-cost evaluation of the project with a market test. If this framework fails to show economic viability, this project is not economical and should not be built. Table 2 – Example of How Much Customers Pay for Transmission Access V. EXAMPLE OF A SEAMS PROBLEM RELATED TO TRANSMISSION LOADING RELIEF BETWEEN ISO/RTO AND NON-LMP MARKETS The distribution of revenue is shown in Table 3. The Transmission Company is paid the guaranteed return plus a share of the market value adder. This sharing of the market value adder is according to the percentage of total ownership (counting both Tier 1 and Tier 2 investments). Thus the Transmission Company receives $3.4 million, while the three States also receive their shares of $0.27, 0.78 and 0.54 millions, respectively. Currently, in the Eastern Interconnection of the North American power grid, coordination between LPM markets and non-LMP markets for congestion management is one symptom of the seams problems. Transmission Loading Relief (TLR) using the Interchange Distribution Calculator (IDC) for flowgates that are impact by both types of markets require both markets to re-dispatch or curtail their market operations. Equity issues arise. Revenue Allocation Transmission Owner State A State B State C Total Capital 100 8 23 16 147 Market Tier 1 Value Guaranteed Adder %Share 15.06 3.40 68.0% 0.27 5.4% 0.78 15.6% 0.54 10.9% 15.06 5.00 100.0% Tier 2 %Share 0.47 17.0% 1.34 48.9% 0.93 34.0% 2.74 100.0% In an LMP market, security constrained dispatches are performed every 5 or 10 minutes. In anticipation of overloading a common flowgate, the LMP solution would have already adjusted the dispatch to stay within that flowgate limit. If a TLR is called on that flowgate due to subsequent flow increases, assigning flow curtailment amounts to the two different markets raises the equity question. Should the LMP market be given a credit for its prior “re-dispatch” in anticipation of the flowgate limit? How can that amount be determined? Total 18.46 0.74 2.12 1.48 22.80 Table 3 – Example of How Revenue is Allocated Tier 2 revenues go only to the three States and not to the customers in the States, according to their relative share of the Tier 2 investments, shown earlier in Table 1. It is up to the States to decide how to use their Tier 2 revenues for their residents, of whom electricity customers are only a subset. Thus, State B, having incurred greater Tier 2 costs than the other two States, receives $1.34 million in Tier 2 revenue, as compared with $0.47 and 0.93 for States A and C, respectively. A market solution to this problem is to introduce the Automatic Transmission Toll Collection system [4]. If a realtime congestion-based toll charge is collected on that common flowgate, based on computed usage of that flowgate by the two markets, then the two markets will respond to the price signal and the actual transmission usage charges that they incur. This is applying the principle of internalizing previous externalities into the market decision. It is similar to relying on a congestion-based toll charge for a bridge to let the users decide 5 whether to pay the toll or take a different route. The concept of an equitable claim on the bridge capacity is irrelevant in a market system. If the congestion remains on the flowgate, the congestion toll charge will increase until the flow pattern changes from both markets for the flow to return to below its limit. VI. HOLISTIC TRANSMISSION EXPANSION PLANNING One new way of looking at transmission expansion is to apply the concept of the Community Activity Room (CAR) to the problem [1]. A new paradigm recognizes that in a power market, power plant and transmission investment decisions are made separately by different business entities. Transmission investments may be more suitably handled with the nondiscriminatory objective to expand the size of the CAR in order to accommodate as much of the generation and load market activities as possible. The tradeoff which puts a limit to the transmission investments would be between costs and the potential curtailment of the electricity energy market due to lack of transmission capacity. Figure 2 – Sample System Before Expansion A technique has been developed by the author to solve the following problem. Given an existing transmission grid, the boundary of the CAR can be determined in the operating space of the generation and load injections, aggregated and reduced to a three-dimensional operating space. Historical hourly records of the generation and load injections can be statistically analyzed and then aggregated and reduced in dimensions. These data can be modeled by Gaussian probability distributions and then projected into future years. The mathematical problem of expanding the walls outward in order to tangentially bound and enclose the Gaussian probability distributions can be solved analytically. The result would be a holistic set of transmission capacity increases which are needed to enable the market to freely move within the CAR in a future period. 2-4 1-4 This concept is demonstrated on a simple network and shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. In Figure 2, the operating space without any transmission overloads is indicated by the white area. The color bands represent increasing levels of overloads if the operating point goes outside of the white area. If it is desirable to allow future operation to enclose a new operating point at the coordinates of (6000, 6000), the best way to expand the transmission system is to push two walls outward, as indicated by Figure 3. The lines from bus 2 to bus 3 and from bus 1 to bus 4 should be increased in capacity accordingly. The resulting feasible operation region, as shown in the white area of Figure 2, should the holistic effect of this transmission expansion plan. Figure 3 – Sample System After Expansion VII. R & D RECOMMENDATIONS This paper has challenged the way we treat transmission as a business. It has proposed a Third Way economic system called UDI-ism that holds some promises for improving the capitalistic market system. It has proposed the idea of applying UDI-ism to the power market problems, especially in the transmission planning and operation area, building on top of the concept of the Community Activity Room (CAR), Virtual Regional Transmission Organizations, and Automatic Transmission Toll Collection. The power of this direct approach is promising. More research is needed to verify its accuracy. More research is also needed to apply it to larger systems. It offers the potential to develop coordinated regional transmission plans and to visualize the holistic benefits in a way and in a metaphor that common people can understand. 6 [5] S. T. Lee, “An Automated Transmission Toll Collection System and Virtual RTO Enable Transmission Investments in a Hybrid Power Market”, EPRI Technical Update, #1002636, November 2003. Research is proposed along the following areas: 1. Methodologies for quantifying and obtaining market values for Tier 2 assets 2. Simulation of consumer and business behavior under UDI-ism 3. Evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages of UDI-ism, as compared with capitalistic market system 4. Evaluation of incentive systems to induce the economic expansion of a transmission grid to provide public benefits under a power market 5. Methodologies for determining holistic transmission expansion plans using the CAR concept [6] Joseph Stiglitz, The Roaring Nineties, Penguin Books, 2003. [7] Bill Emmott, 20:21 Vision – Twentieth-Century Lessons for the Twenty-First Century, Picardor Edition, March 2004. BIOGRAPHY Stephen T. Lee (IEEE M’69, SM’75) is Technical Executive, Power Delivery and Markets, in EPRI. Dr. Lee has over 30 years of power industry experience. He received his S.B., S.M. and Ph.D. degrees from M.I.T. in Electrical Engineering, majoring in Power System Engineering. He worked for Stone & Webster Engineering in Boston, Systems Control, Inc. (now ABB) in California, and he was Vice President of Consulting for Energy Management Associates (EMA). Before joining EPRI in 1998, Dr. Lee was an independent Consultant in utility planning and operation. At EPRI, Stephen Lee is leading technical research programs for grid operations and planning and power markets. He is also active in the North American Electric Reliability Council (NERC) on issues related to interregional operation and planning. He has been actively developing new concepts and tools for power system operation and probabilistic transmission planning. REFERENCES [1] S. T. Lee, “Community Activity Room as a New Tool for Transmission Operation and Planning Under A Competitive Power Market,” IEEE Power Tech 2003 Conference, Bologna, Italy, June 2003. [2] Stephen Lee, “Virtual Regional Transmission Organization”, Energy Pulse (www.energypulse.net), May 27, 2003, [3] S. T. Lee, “Virtual Regional Transmission Organizations And the Standard Market Design – A Conceptual Development with Illustrative Examples,” EPRI Technical Update, #1007680, January 2003. [4] Stephen Lee, “Automatic Tolls Enable Transmission Investments in a Hybrid Power Market,” Energy Pulse (www.energypulse.net), November 11, 2003. 7