1 1974

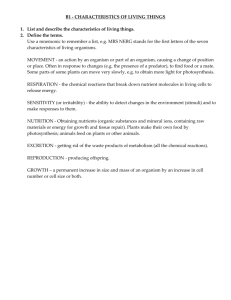

advertisement