by A. (1986) University of California at Los Angeles

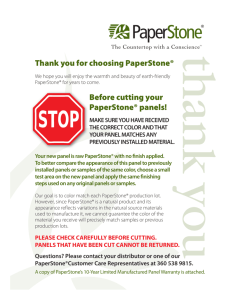

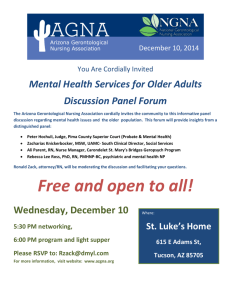

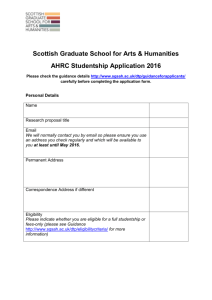

advertisement