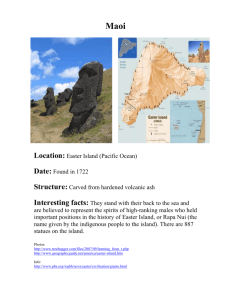

An illustrated and annotated checklist of freshwater diatoms

advertisement