Q L Pe

advertisement

Student Writing Samples

6+1 Trait: Sentence Fluency

There Was An Old Lady Who Swallowed a Trout

r"

There was an old lady who

swell owed a ""","Y...::.A...:....dI...--S_ __

There was an old /Crdy who

-

I

.~

l)

.

r~

swallowed

a

'1·I:t~

_Vi

_('

~e FAt;~\J-t

(

Le

~~., ~\ ',-:<

Pe L

Q

~I

~)\

,

~

1

She

____

~K N\

..'ff'

.,,~~

i,

S ~\\ ~\ ~

.

(

if

'/

':

-

-

- \,

l

\

-

swall~wed a LAJHe~L.

She swallowed _0

S11

~,K

Emergent Literacy Translation:

Emergent Literacy Translation:

Her face got pale. She swallowed a whale.

There was an old lady who swallowed a snake.

The snake came awake. She swallowed a snake.

~here was an old lady who swallowed a whale.

There was an old lady who

There was an old lady who

!iWQllow~d-'l..p i ~ .'.

-jt

"{VEl)

hr

,Ij

h·

swallowed a --'-C.....::,c. .)\--:..-t.. _ _ _ -

-OCOtCA·

.

5 he swa II owe d a -+\ \-_ c) ItJ

'--

Emergent Literacy Translation:

There was an old lady who swallowed a fish.

It was her wish. She swallowed a fish.

i

-She ,swGYowed a

.

lOS 0

C Cf

t

Emergent Literacy Translation:

There was an old lady who swallowed a cat.

A cat tasted like a rat. She swallowed a cat.

Literature to Teach Writing 71

Response: There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Trout

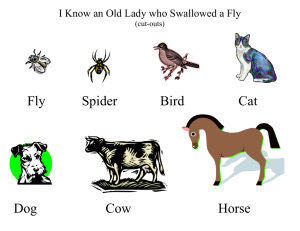

I chose to use this book because we were engaged in a study on water habitats.

Since the children were familiar with the traditional version of this story, There Was an

Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly, I thought it would be a great idea to read a new, original

version. The kids really enjoyed this version, however, there were a few things I would

change. First, I would definitely read both stories to the children. Although they had

heard the story before, it was not fresh in their memory. Next time, I would read the

traditional story one day, discussing the rhymes, rhythm, and pattern. We would briefly

discuss things the students liked about the story. I would then try to get their ideas

coming by brainstorming: "What other animals might the old lady swallow? Can you

think of a rhyme to go along with that animal?" I would take a few minutes to take

suggestions and compile a list of animals and rhyming words.

Then the next day, we would begin by reviewing our list of animals and rhyming

words. Before reading the second story, I would ask students to predict what kinds of

animals might be included in this version of the story. After reading, I would follow the

same progression for discussion and brainstorming, this time going more in depth. Our

list would grow until all students felt that they had a unique idea about which they would

like to write. I feel this two-day approach would be much more effective because it

would give the students more background knowledge, confidence, and experience in this

style of writing.

Literature to Teach Writing 72

6+ 1 Writing Trait: Sentence Fluency

If You Give a Mouse a Cookie

By Laura Joffe Numeroff

Prereading:

Introduce the "If... then... " structure for writing a sentence with the following

statement: "If everyone will sit on the floor, then I will start the story."

Ask students to come up with some other statements they hear often that use the "If..

.then" structure. Here are some examples:

"If you eat all your dinner, then you may have some dessert."

"If you clean up your room, then you may watch T.V."

"If you finish your homework, then you may go outside to play."

"If you eat some peppers, then you will be thirsty."

"If you don't brush your teeth, then you will get cavities."

Discuss the kinds of statements these are. They are cause and effect. If one thing

happens, then another thing will happen.

Tell students that the book we are going to read is full of these kinds of sentences.

Show them the cover of the book and help them to read the title. Ask students to tell

how they think the author will complete the statement: "If you give a mouse a cookie ..

." After sharing several suggestions, tell students to check their predictions as we read the

story. Also, direct students to pay particular attention to the way the story flows from

one event to another because of this "If... then" structure.

Reading:

Be sure to read the sentences smoothly, so children can feel the fluency and

-

rhythm this type of text creates. If you want to stop, choose a place in between

Literature to Teach Writing 73

sentences, in order to keep the continuity of the text. During reading, allow students to

make predictions to complete the "then" part of the statement. Point out how the author

does not have to say "if' and "then" every single time because after awhile, the reader

automatically understands the structure.

Prewriting:

Spark a brief discussion of the text. Ask students to share opinions about the

story. Possible discussion questions: "Why do they like it? What makes it fun to read?

What do you like about the author's style?" If there is time, you may choose to read

another book by Numeroff that uses the same style:

If You Give a Mouse a Muffin or If

You Give a Pig a Pancake.

Brainstorm ideas for your own story. Choose a new character, possibly a

different animal, to be the main character in the story. Then begin listing possible things

for the character to do. After many ideas have been suggested, choose the one that leaves

the most possibilities for connecting the sentences fluently.

Writing:

As a class, write a progression of events for your character. Try using the "If..

.then" structure for some sentences, but remember to vary the structure for others.

Remind students to focus on making the sentences flow smoothly together. After the

class story is written, distribute pages for the class book. Have each student, or pair of

students, write the words on the page and illustrate it. Compile the pages to make a

complete story and class book.

Literature to Teach Writing 74

,~

~

~.

~..

'

;$~

~

'*~

~,.,

'~

~~

~.

~

.

,~

*'W

~

~.

~~

~1'

.~

......

W'

(J}

:

~-~-

---

j

Literature to Teach Writing 75

'('"..:.

~~

~

.;.t

6+ 1 Writing Trait: Conventions

No, David!

by David Shannon

Prereading:

Give two examples of the same phrase with different punctuation on the board. s·. .~

For example: "No class!" "No, class!" Have two students read the sentences. Ask

students to explain how they're different. Talk about how the comma changes the

meaning of what we write.

Commas are used correctly and carefully in the book we're going to read. It's a

book that shows all the rules the author was supposed to obey as a child. Rules and

giving directions are also called commands. Commas are used often when giving

commands. There aren't many words in the book, so I want you to pay attention to the

commas. See if you can figure out a rule that explains when or how commas are used in

commands.

Reading:

As you read aloud, tell that students to look carefully at the few words included in

the book. You may wish to follow the text with your fmger to focus student's attention

on the text. Be sure to indicate a pause in your reading when a comma exists. After

reading it once, ask students to share their observations. Guide them to clue in on the

word that often is used with the comma: David, his name. Read the story again so

students can check to see if the suggestions from the class are correct.

Literature to Teach Writing 76

Prewriting:

Practice writing commands as a class. Brainstonn commands that teachers might

say in the classroom. For example: "Sit down, Brett." "Tie your shoe, Carly." "Listen

carefully, Shawn." Also, try examples where the name might come at the beginning of the

command. "Cindy, don't push." "Ryan, feed the fish."

Discuss how students feel when people are constantly saying "No!" or "Don't!"

Is it a positive response? Ask which sounds more pleasant. "No running, Phil!" or

"Please walk, Phil!" Keep this in mind when you speak to people or give advice. People

are more likely to listen if you write or say things in a positive way.

Writing:

Students are going to write a book of advice for younger students. Each student

could receive a list of names to include in their book. A class could be divided up

according to tables, alphabetical order, or selected at random. If this is too complicated,

allow each student to select one younger student and write all advice for just that one

student.

Sample:

Advice/or First Grade

Paul, remember your homework!

Eat a good breakfast, Rachel.

Follow your teacher's directions, Ed.

Allie, read lots of books.

Be nice and make friends, Josh.

j

~::'''''

~~

:!'

.::,'

Literature to Teach Writing 77

6+ 1 Writing Trait: Conventions

From Head to Toe

by Eric Carle

Prereading:

Put the three main punctuation symbols on display: period, question mark,

exclamation point. These can be drawn on the chalkboard, cut-outs that are shown, etc.

Ask students to tell what they are. "What are they used for? Give an example of a time

we would use them." After students are reminded about each mark and when it is used,

tell them to look carefully for these punctuation marks in the story. Tell them to see

what they notice about the three marks. "How are they different? How are they the

same? Why are they important?"

Reading:

While reading the story, be sure to emphasize inflection in your voice. Make

obvious distinctions between statements and questions by raising the tone at the end of

your voice. Consider adding nonverbal cues, too, such as head nods, shoulder shrug, and

eye contact. Nonverbal behavior for exclamatory sentences can be even more obvious by

showing excitement in your body language.

Prewriting:

After reading the story once, ask students to tell what they noticed about each

kind of punctuation. Notice that a period is used at the end of a sentence that is telling

information. Discuss how these marks are useful to us as readers. These symbols let us

.-

know how to read it and what it would iOUPd like if someone was really saying it. Ask

Literature to Teach Writing 78

students if they noticed a pattern in the book. It began with a statement, then a question,

and ended with an exclamatory sentence. This pattern gave structure to the sentences

and made it extremely important that the author used punctuation carefully.

Now we'll write our own story like From Head to Toe. Brainstorm unique ideas.

This will be a class book. Try using different settings and characters. Rather than

animals, it could take place at an amusement park and the characters could be the rides

and attractions there. For example: "'I am a rollercoaster and I can flip people upside

down. Do you want to ride? 1 will ride!" The next student might choose to write about a

water ride. "I am a big innertube and I take people under waterfalls. Do you want to

ride? I will ride!" Allow each student to select a different attraction and write their three

sentences and illustrate it. Combine to make a class book. (Other possible settings

include: circus, zoo, grocery store, restaurant, sporting event, etc.) Another example:

"This is a pear and it tastes sweet and juicy. Will you eat it? 1 will eat it!"

Literature to Teach Writing 79

,-

Literature to Teach Writing 80

6+ 1 Trait: Presentation

Various types of literature are appropriate.

There are a myriad of strategies and styles to use in the presentation of students'

writing. It is important to use a variety of these methods in writing. These unique and

special styles of presentation make students excited about writing. It is very encouraging

to share fmal pieces in a unique way. The following is a list of general ideas and

suggestions for presenting student work. In some cases, pictures from the lessons I

piloted are included as examples. For even more strategies, consult the professional

resources at the end of the paper! Most importantly, remember that sharing what you

write should be a fun and enjoyable experience! Help your students love to write and

share!

Class Books

When students are learning to write, it is often helpful to write books together as a

class. These works are called "class collaborations." These often take the shape of text

innovations, when the class writes using the same structure or plot line as the work of

literature. This shared writing experience is a good way for teachers to model the writing

process. Other class books can be created by combining work by individual students. In

this case, students each write their own page. Class books make an excellent addition to

every classroom library. They can also be sent home on a rotating basis or displayed in

the school library.

Literature to Teach Writing 81

Individual Books

In some cases, it is more appropriate for students to each make their own book.

This is most effective in establishing each child as an author. This is also beneficial

because it is something the student can take home with them. Hopefully, it can be used

for practice in reading, as students will continue to share their book with others.

Computer - Word Processing for Students

Technology has allowed the improvement of displaying writing. Even from a

young age, students should utilize computers for their writing. Using word processing

programs or other student writing programs can be a great way to familiarize students

-

with computers. It also makes writing appear very professional and can make students

feel important as writers. There are unlimited possibilities for writing on the computer.

Often, children enjoy simply experimenting with writing and images on computers, as

well.

Power Point Slide Show

For an interactive method of presentation, students can create a power point slide

show. This consists of screens on which students display writing and visuals. Slide

shows are often utilized for factual infonnation, but can be equally effective for fiction

writing, too. These slide shows are excellent visual aids to accompany a presentation or

speech. With little assistance, students can create a professional presentation of their

writing.

Literature to Teach Writing 82

Website

Sometimes, students wish to share their writing with many people. In this case, it

might be appropriate to develop a website. This kind of writing often takes the forms of

written discussions or posting a message board. However, students might want to create

an informational web page about their research topic. Although this presentation can

complicated, its rewards could make it all worthwhile.

Reading

Another important component of presentation, is the opportunity to share

writing. Students need the opportunity to read their writing aloud to various types of

-

audiences. Students should begin by reading it to one friend or the teacher. Gradually,

then the student can read to his or her class, other classes, or even larger audiences. This

is a nice technique for sharing writing at parent-teacher conferences or school events.

This component of presentation is often overlooked, when it is one of the most essential

ways that writing is presented.

Literature to Teach Writing 83

These books were collaborative1y created by students.

They are among the most frequently read in the classroom library.

Teady Bear. Teddy Bear

Whet do you see'

t@

i'

This shows the cover and first page of an individual book

One student proudly displays her completed book,

which she \\-Tote and illustrated herself.

when i go to theocean i like

to see hammerhead sharks

The text and illustrations of this piece were

created by a student using the computer.

Literature to Teach Writing 84

Accountability

Alignment with State Standards

As with any educational program, it is important to consider how this writing

program facilitates the achievement of educational goals. The standards established by

each state serve as an important guide for designing curriculum and instruction. Although

the standards will vary a little from state to state, the same basic writing skills are always

required. After analyzing the Indiana Standards for reading and writing in the primary

grades, I saw that the lesson strategies utilized in my project correlate highly with those

objectives in the standards. This shows that the use of quality literature, the writing

process, and 6+ 1 traits creates a comprehensive writing program that aligns with the

priorities and expectations set by the state of Indiana.

The following reference charts illustrate this alignment with the standards.

Because these lessons are designed for use in any or all of the primary grades (K-3), the

chart compiles the common standards that apply to several grades. The first column lists

a description of the general standards that includes several specific expectations at each

grade level. The second column, explains how the lessons I developed help students to

achieve these standards. Finally, the last four columns display the number of the specific

standard for each grade, which teachers can consult for more specific information. These

are the standards that are addressed in each of the lessons included in this project.

Literature to Teach Writing 85

READING STANDARDS

General

Description of the

Reading Standard

How my lessons

attempt to promote

mastery of the skill

Kindergarten

Read aloud fluently

Teacher models fluent

grade

2nd

grade

grade

-----

1.1.15

2.1.6

3.1.3

K.1.1;

K.2.1

1.3.2

2.2.4

3.2.1

-----

K.1.3

1.3.2

2.2.2,

2.2.3

K.3.4

1.2.3

2.2.4

3.3.2 3.3.6

K.2.2K.2.5

1.2.4 1.2.7

2.2.2 2.2.8

3.2.2 3.2.7

K.3.1

-----

-----

3.3.1

K.3.3

1.3.1

2.3.4

3.3.5

lst

3111

.l.•

Identify parts of a

book

Recognize the

purposes for

reading and the

author's purpose

for writing

Respond, discuss,

question, and

analyze what is read

Utilize strategies

that improve

comprehension

Recognize and

differentiate

between genres

Identify the use of

various writing

devices and

techniques

Provides exposure and

interaction with many

books.

Discuss the roles of

authors and readers.

Teacher leads

discussions and

involves students in

higher-order thinking.

Teacher models that

use of these strategies

and prompts students

to use them as they

read.

Students read a wide

variety of literature.

Teacher uses

prereading activities to

focus students'

attention on effective

strategies used by the

author.

Literature to Teach Writing 86

WRITING STANDARDS

General

Description of the

Writing Standard

How my lessons

attempt to promote

mastery of the skill

Find and discuss

ideas for writing

Teacher helps students

to draw ideas from the

literature that they

read.

Teacher models

organizational

strategies to use in

writing.

Students conference

with teacher and peers.

Organize ideas and

content in planning

and writing

-

.

Revise original

drafts to improve

quality of writing

Publish quality

work using various

resources and

technology

Write in various

forms and genres for

different purposes

and audiences

Utilize correct

written English

conventions so

writing is easily

understood

Teachers give

opportunities to

present writing in

many forms.

Teachers provide a

variety of writing

activities, each with a

unique purpose and

audience.

Teacher provides good

models, instruction,

and opportunities for

authentic writing.

3rd

Kindergarten

1st

grade

2nd

grade

grade

K.4.1

1.4.1

2.4.1 ;

2.4.3

3.4.1;

3.4.2

K.4.5

104.2

2.4.2

304.3

-----

104.3

2.4.8

3.4.6;

3.4.8

KA.3;

KA.4

-----

204.3 2.4.5

3.4.4;

3.4.5

K.5.1 K.5.2

1.5.1 1.5.5

2.5.1 2.5.6

3.5.1 3.5.5

K.6.1K.6.2

1.6.1 1.6.8

2.6.1 2.6.9

3.6.1 3.6.9

Literature to Teach Writing 87

Reflection

Literature to Teach Writing 88

Reflecting on Literature in the Writing Program

After all of my research and trials using these lessons in the field, I have reached

the following conclusions:

#1: Literature is an essential component of the writing program.

After my observation and participation in the teaching of writing at various

schools and grade levels, I really feel that literature strengthened writing instruction in

every case. Although I observed teachers using a wide variety of strategies, all of them

utilized literature in some way. Of course literature was not used for every single lesson,

but it held a significant position as an instructional tool for the overall program. Through

the lessons I developed and piloted, I noticed an overall improvement of writing when it

was connected to authentic literature. These are the main things I noticed that literature

provided when integrated with writing instruction:

Dlustrates models of various literary elements

Creates authentic literary experiences

Activates thinking and new ideas

Nurtures enthusiasm and excitement

#2: Teachers playa critical role in writing instruction.

Although literature can playa major role in the writing program, it cannot do it

alone. Students still need an effective, active teacher who does the following things:

Literature to Teach Writing 89

Writes as a model for students

Reinforces student progress and achievement

Instructs in the zone of proximal development

Talks about literature and ideas for writing

Evaluates needs of students to select literature and plan instruction

#3: Students are authors, too!

Many teachers, parents, and even students, themselves, underestimate the ability

of children as writers. I know, because I was one of them. My expectations for writing

performance seemed reasonable to me, even though I unintentionally set them much lower

than they should be. After my experiences in the classroom piloting my lessons, I was

amazed by the outstanding quality of writing my students were creating. With the

appropriate model, motivation, and support, students are able to write very much like the

models they admire.

In conclusion, combining literature and writing has shown many benefits.

Literature is an enjoyable way to model effective strategies for writing. Along with

teacher modeling, students are exposed to many samples of effective writing. Excitement

for literature can produce a great desire to write. Our writers of tomorrow are inspire by

the literature they read today. With support and guidance in writing, students can be

successful and feel competent about their ability as a writer. Finally, our readers have

become writers, who now appreciate the true craft of writing. This cycle can occur in the

Literature to Teach Writing 90

integrated approach to reading and writing instruction. It is a successful tool for teachers

and an extremely beneficial process for students. When quality literature is used by

effective teachers, the results on students are tremendous!

I

C

A

N

W

R

I

T

E

Literature to Teach Writing 91

Resources

Literature to Teach Writing 92

References

These references were used to research the theoretical foundation.

Anderson, N. C. (1998, June). The reading/writing connection. School Library Media

Activities Monthly, 24-26.

Bromley, K. D. (1989, November). Buddy journals make the reading-writing

connection. The Reading Teacher, 122-129.

Bukatko, D., & Daehler, M. W. (1998). Child development: a thematic approach

Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Burton, F. R. (1989). Writing what they read: reflections on literature and child writers.

In J. M. Jensen (ed.). Stories to Grow on: Demonstrations o/Language Learning

in K-8 Classrooms (pp. 97-116). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Butler, A. & Turbill, J. (1984). Towards a reading-writing classroom. Rozelle, NSW,

Australia: Primary English Teaching Association.

Calfee, R. (1998). Leading middle grade students from reading to writing: conceptual and

practical aspects. In N. Nelson & R. Calfee (eds.) The Reading-Writing

Connection (pp.203-228). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Chew, C. (1985). Instruction can link reading and writing. In J. Hansen, T. Newkirk, &

D. Graves (eds.). Breaking Ground: Teachers Relate Reading and Writing in the

Elementary School (pp. 169-173). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Comstock, M. E. (1992, April). Poetry and process: the reading/writing connection.

Language Arts, 261-267.

Literature to Teach Writing 93

Denyer, J. & Florio-Ruane, S. (1998). Contributions of literature study to the teaching

and learning of writing. In T. E. Raphael & K. H. Au (eds.). Literature-Based

Instruction: Reshaping the Curriculum (pp.149-171). Norwood, MA:

Christopher-Gordon Publishers.

Farr, R. (1993). Writing in response to reading: a process approach to literacy

assessment. In B. E. Cullinan (ed.) Pen In Hand: Children Become Writers (pp.

64-79). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Fletcher, R. (1993). Roots and wings: literature and children's writing. In B. E. Cullinan

(ed.) Pen In Hand: Children Become Writers (pp.7-18). Newark, DE:

International Reading Association.

_

Garrity, L. K. (1991). After the story's over: your enrichment guide to 88 read-aloud

children's classics. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, and Company.

Glasser, J. E. (1990, November). The reading-writing-reading connection: an approach

to poetry. English Journal, 79,22-26.

Hansen, J. (1987). When writers read. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Johnson, T. D. & Louis, D. R. (1990). Bringing it all together: a program/or literacy.

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Kilpatrick, S. (2001). Developing young authors: using/avorite literature to model good

writing. Huntington Beach, CA: Creative Teaching Press.

Koch, K. (1990). Rose, where did you get that red?: teaching great poetry to children.

New York: Vintage Books.

Literature to Teach Writing 94

Kruise, C. S. (1990). Learning through literature: activities to enhance reading, writing,

and thinking skills. Englewood, CO: Teacher Ideas Press.

Lloyd, P. (1987). How writers write. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

May, F. B. (1998). Reading as communication (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ:

Merril.

Mealy, V. T. (1986). From reader to writer: creative writing in the middle grades using

picture books. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press.

Nelson, N. & Calfee, R. (1998). The reading-writing connection viewed historically. In

N. Nelson & R. Calfee (eds.) The Reading-Writing Connection (pp. 1-52).

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

--

Neuman, S. B., Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (1999). Learning to read and write:

developmentally appropriate practices for young children. Washington D. C.:

NAEYC.

Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory. The original student-.friendly guide to

writing with traits. Portland: NWREL.

Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory. (1999). Seeing with new eyes: a guidebook

on teaching and assessing beginning writers using the six-trait writing model.

Portland: NWREL.

Sager, M. B. (1989, October). Exploiting the reading-writing connection to engage

students in text. Journal ofReading, 33, 40-43.

-

Sinatra, R. C. (2000, May/June). Teaching learners to think, read, and write more

effectively in content subjects. The Clearing House, 266-273.

Literature to Teach Writing 95

Sipe, L. R. (1993, September). Using transformations of traditional stories: making the

reading-writing connection The Reading Teacher, 47, 18-26.

Spandel, V. (2001). Creating writers through 6-trait writing assessment and instruction

(3rd ed.). New York: Longman

Stewig, J. W. (1990). Read to write: Using Children's literature as a springboard for

teaching writing (3rd ed.). Katonah, NY: Richard C. Owen Publishers.

Tierney, R. J., & Shanahan, T. (1996). Research on the reading-writing relationship:

interactions, transactions, and outcomes. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. Mosenthal,

& P. D. Pearson (eds.). Handbook ofReading Research, Vol. II (pp.246-280).

Mahwah, NJ: Lawerence Erdbaum Associates Publishers.

Tompkins, G. (1998). Language arts: content and teaching strategies. Upper Saddle

River, NJ: Merri1.

Walmsley, S. A. & Walp, T. P. (1990, January). Integrating literature and composing

into the language arts curriculum: philosophy and practice. The Elementary

School Journal, 90,251-274.

Literature to Teach Writing 96

Professional Resources

Consult these sources for many more lesson ideas that link: literature to writing.

Carey, P., Hozschuher, C., & Kilpatrick, S. (1995). Activities for any literature unit,

primary. Huntington Beach, CA: Teacher Created Materials.

Carroll, J. A. (1991). Picture books: integrated teaching ofreading, writing, listening,

speaking, viewing, and thinking. Englewood, CO: Teacher Ideas Press.

_ _. (1992). Story books: integrated teaching ofreading, writing, listening, speaking,

viewing, and thinking. Englewood, CO: Teacher Ideas Press.

Cerbus, D. P. & Rice, C. F. (1995). Whole language unitsfor predictable books.

Huntington Beach, CA: Teacher Created Materials.

-

Culham, R. (1998). Picture books: an annotated bibliography with activities for teaching

6-trait writing. Portland: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory.

Fairfax, B. & Garcia, A. (1992). Read! Write! Publish! Making books in the classroom,

grades 1-5. Cypress, CA: Creative Teaching Press.

Gruber, B. & Gruber, S. (1990). Literature library, volume 2, grades kindergarten-I.

Palos Verdes Estates, CA: Frank Schaffer.

Kazemek, F. E. & Rigg, P. (1995). Enriching our lives: poetry lessons for adult literacy

teachers and tutors. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Kilpatrick, S. (2001). Developing young authors: usingfavorite literature to model good

writing. Huntington Beach, CA: Creative Teaching Press.

Norris, J. & Evans, J. (1997). Literature & Writing Connections: how to make books

with children series. Monterey, CA: Evan-Moor Corporation.

Literature to Teach Writing 97

_ _. (1997). Read a book - make a book: how to make books with children series.

Monterey, CA: Evan-Moor Corporation.

Sterling, M. E. (1991). Patterns/or big books. Huntington Beach, CA: Teacher Created

Materials.

Walsh, N. (1997). Making books across the curriculum: pop ups,jlaps, shapes, wheels,

and many more. New York: Scholastic.

Literature to Teach Writing 98

Children's Literature

These children's books are the basis of the application activities for each trait.

Brett, J. (1989). The mitten. New York: Scholastic.

Brown, M. (1991). Arthur meets the president. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Carle, E. (1997). From Head to Toe. New York: Harper Collins Publishing.

Curtis, J. L. (1999). Today Ifeel silly and other moods that make my day. New York:

Scholastic.

Lionni, L. (1992). A busy year. New York: Scholastic.

Marzollo, J. (1992). Happy Birthday, Martin Luther King. New York: Scholastic.

Numeroff, L. J. (1985).

Ifyou give a mouse a cookie.

New York: Scholastic.

Shannon, D. (1998). No, David! New York: Scholastic.

Sloat, T. (1998). There was an old lady who swallowed a trout. New York: Scholastic.

Small, D. (1985). Imogene's antlers. New York: Crown Publishers.

Viorst, J. (1976). Alexander and the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day. New

York: Scholastic.

Yolen, J. (1987). Owl moon. New York: Putnam Publishing Group.

Walton, R. (1998). Why the banana split? New York: Scholastic.

Literature to Teach Writing

99

Literature Links to Traits

A bold asterisk indicates the trait that the included lesson plan teaches for each book.

Regular asterisks identify other traits the book might be helpful in teaching.

~

Book Title

rIl

'~

"=

"0

~

-

.....0==

.....'N"=

==

'OJ)

"=

(,J

~

(,J

~

.....0

.....0

.c

(,J

U

>-

"0

0""

""

0

~

==

rIl

~

(,J

-

==

==

0

~

-=

~

~

==

~

.....==0

==

~

>

u

r71

A Busy Year

Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible,

No Good, Very Bad Day

Arthur Meets the President

*

*

*

*

*

From Head to Toe

Happy Birthday, Martin Luther King

If You Give a Mouse a Cookie

Imogene's Antlers

*

*

*

*

* *

*

* *

*

The Mitten

No, David!

*

*

*

*

* *

*

*

Literature to Teach Writing

100

>-.

Book Title

C"I.l

=

~

"C

~

Q

.....

.....=

N

.....=

=

=

-.

ell

~

~

.CJ

Q

:>

*

Today I Feel Silly! And Other Moods

that Make My Day

Why the Banana Split?

"C

-.

~

*

There Was An Old Lady Who Swallowed a Trout

.c

U

Q

0

Owl Moon

.....QCJ

= =

-= .-.....=

>

=

=

..... u

=

rI'1

C"I.l

~

Q

~

~

~

~

Q

CJ

~

*

*

*

*

*

*

CJ

*

*

)

)

)

Students enjoy listening to a new story.

Students write in their journals during a guided reading and writing lesson.

t:

....

(])

'"1

!?!

q

(])

.....

o

-l

(])

~

::r

~

'"1 .

,...

....

.....

~

GO

>-'

o

.......

Students follow along as the teacher reads aloud from a big book.

Teacher provides assistance and support to a young writer.