Footnotes & Bibliography Guide

advertisement

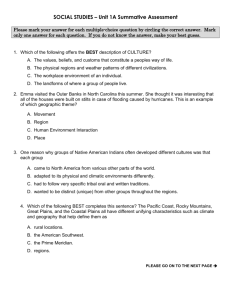

Footnotes & Bibliography Guide Footnotes are a simple way to organize in-text citations for a poster or presentation, and allow a more coherent flow free of distraction from bulky parentheticals. For reports, footnotes are typically only used in the Chicago bibliography format. For Dr. Vonhof’s poster project, footnotes can also be used with a correctly formatted and consistent MLA or APA bibliography. At the bottom of your poster, place a shortened bibliographic section titled “references” or “notes”. Attach your bibliography on an 8.5x11” separate page. Formatting footnotes on your poster 1. Every time you use an idea, fact, or direct quote from an outside source, place a superscripted number after the period of that sentence. 2. Each time you do this, you must use a new footnote, even if the same source was used previously in your poster. You should never use the same footnote number twice. 3. Your footnote numbers must be ordered numerically. The first footnote appearing on your poster is be 1, the next footnote used is 2, and so forth. Proofread your poster to make sure the order did not get messed up after editing, and you’re not missing or repeating any footnotes. 4. If you use multiple sources in one sentence, use a different number for each source, all superscripted and listed in order separated by commas after the period. Formatting references section of your poster 1. List your footnotes numerically, following the same order in your References section as they do in the body of your poster’s text. 2. If the same source is used multiple times in a row, for the second+ footnotes write “Ibid” in italics. If the page number is different, write “Ibid., #.” 3. If the same source is referenced multiple times, but not consecutively, you cannot use Ibid. You can write a shortened version of the footnote, though. After the first footnote for a source, any consequent references of the same source must only include the author’s last name, part or all of the work’s title, and the page number. Formatting Chicago style bibliography 1. The bibliography goes on a separate page at the end of your report or attached to your poster. The page should be titled “Bibliography”, centered at the top of the page in plain text. 2. Enter each source alphabetically by author’s last name, or the first word to appear in the citation. Ignore “a”, “the”, or “and” when alphabetizing. Do not number the entries. 3. Each entry should be single spaced, with double spacing between entries. 4. The first line of each entry should not be indented. All following lines of each entry should be indented ½ inch. In Microsoft Word, you can use the “hanging indent” feature to accomplish this, found in the Format…Paragraph section under the “Special” menu in the “Indentation” section. Adjust “Hanging” to 0.5. What not to do 1. The footnotes at bottom of poster are NOT a bibliography. The bibliography should include many sources that were never directly referenced on your poster, and be formatted much differently than your poster’s “references” section. 2. Do not leave out any sources that you used during any part of your project. Even if you used a source simply to narrow down what not to include on your poster – include it in the bibliography. Claiming ideas that you took from a source as your own is plagiarism, even if you don’t use direct quotes. 3. Do not forget to proofread your footnotes after you’ve finalized your poster – ensure a correct order and that everything is cited properly. Don’t accidentally plagiarize. How to Write a Bibliography: Chicago Style A simple guide to writing footnotes can be found on the Chicago manual of style website: http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html Below are some commonly used sources. Footnotes: Book 1. Firstname Lastname, Title: Subtitle (City: Publisher, Year), pg-pg. 2. Last, Title, pg. Online Book 1. Firstname Lastname, Title: Subtitle (City: Publisher, Year), url. 2. Last, Title, chapter/section/page. Online Journal Article *If available, include DOI (permanent identifier for article, see http://dx.doi.org/ to plug it in) 1. Firstname Lastname and Firstname Lastname, “Article Title,” Journal Title Edition# (Year): page-page, doi: ##.####/######. 2. Lastname and Lastname, “Title,” page. note: if there is no DOI, include url as last section of footnote citation. Website 1. “Article/Site Title,” last modified Month xx, Year, full url. 2. “Article Title.” Article from Magazine/Newspaper 1. Firstname Lastname, “Article Title,” Magazine/Newspaper Name, Month xx, xxxx, page. 2. Lastname, “Article Title,” page. Bibliography: Book Lastname, Firstname. Title: Subtitle. City: Publisher, Year. Online Book Lastname, Firstname. Title: Subtitle. City: Publisher, Year. (Kindle Edition)(Google Books)(full url). Online Journal Article Lastname, Firstname and Firstname Lastname. “Article Title.” Journal Title Edition# Year: pages. Accessed Month xx, xxxx. doi: xx.xxxx/xxxxxx. Website Title of Website. “Title of Article/Page.” Accessed Month xx, xxxx. Full url. Article from Magazine/Newspaper Lastname, Firstname. “Article Title.” Magazine/Newspaper Name, month xx, xxxx. full url. Secondary Citations: Secondary citations are used when you quote a primary source, but took the quote from a secondary source such as a book or website. This way you can cite primary sources even if you didn’t consult the original source, and the reader can still find where you obtained your quotation. First, you must cite the original source, and second, the source from which you took the quote (i.e. the secondary source in which you found the primary source quote). Lastname, Firstname (of original quote). Title of original primary source. Date of original quote. Cited in Author, Title (publication info) page #. In the example below, the writer used a quote from Robert Cushman, but found the quote not in Cushman’s original article published in 1621, but in a book by author Gregory Nobels published in 1997. Cushman, Robert. “Reasons and Consideration Touching the Lawfulness of Removing Out of England in the Parts of America.” 1621. Cited in Gregory H. Nobels, American Frontiers: Cultural Encounters and Continental Conquest (New York: Hill and Wang, 1997) 30-31. Further Resources Chicago Manual of Style http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/ Purdue OWL https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/section/2/ University of Wisconsin footnotes and bibliography guide http://www.uwosh.edu/history/student-information/history-style-guide/part-3guide-to-writing-footnotes-and-bibliographies Below is an example of a paper (the text of a poster) with correctly formatted footnotes, references section (that would be placed at bottom of poster), and bibliography (separate from poster, handed in attached). With the opening of the Great Plains region of the U.S. for settlement in the 19th century came unprecedented opportunity for any citizen to claim land and own a farm. From the original five thousand inhabitants of the Dakota Territory at its formation in 1861, incredibly cheap land from the Homestead Act of 1862 inspired the population boom to over 430,000 by 1885.1 Dakota Territory settlers’ lack of knowledge of the region’s soil and climate fostered the growth of new farming methods and the rise of large-scale farming in the late 19th and very early 20th centuries, which are still prevalent in 21st century agriculture. The initial wave of Westward settlers were not experienced agriculturalists, but everyday Americans seeking the economic opportunity of owning a successful farm. The common expectation was that the new lands out West would be comparable to those from the settlers’ homes, and farming them would be much simpler than it actually was. In truth, the dry Dakota Territory climate was very different from the humid climate of the more heavily forested Eastern regions most farmers were used to.2 Advanced knowledge of soil sciences informs agriculturalists today that the Dakotas have black, “grain-producing” soils very different from the clay soils in the Eastern United States.3 But before 1900, “even the federal agencies had learned very little about soils”.4 The first soil survey was not conducted until 1899 in the U.S., and there was no “classified body of knowledge” of soil sciences to guide homesteaders.5,6 Homesteaders on the Plains would plant the crops that they knew to be successful elsewhere. “[B]ut their previous farming experience was not always a reliable guide”, and soon most crops failed.7 The crops that were most drought-resistant survived: namely wheat and barley. Durum wheat and hard redspring types of wheat were being widely grown in the Dakota Territory by 1879, which are the hardiest cereal grains for an arid climate.8 Hardy Webster Campbell, when he homesteaded in the Dakota Territory in 1879, noticed that the crop yield was “not what [it] might be” were the lands used properly.9 He implemented a dry farming system over the next decades, publishing his “Soil Culture Manual” on the subject in 1902, bringing the centuryold farming techniques to popularity on the Great Plains. This was a way to farm the semi-arid region of the Northern Great Plains without irrigation. It was a solution to crop failure due to drought, and was relatively inexpensive and simple to implement using basic plows and tools that were already commonly in use. However, this practice was overused and misunderstood, and implemented in a way that was terrible for the land, literally uprooting entire farms after only a few years of use. An immediate impact of overuse of dry farming was the devastating Dust Bowl of the 1930s, wherein millions of acres of land erosion were caused by the common misunderstanding of Campbell’s methods. Bonanza farms were another new farming style originating in the Dakota Territory in the 1870s. These were massive farms harvesting thousands of acres of wheat at a time. This was a way to cope with the unfamiliar lands; the settlers knew wheat was successful and used the large tracts of cheap land from the railroad companies in the late 19th century to reap huge profits. By 1900, North Dakota had over 1,300 farms with thousands of acres of wheat, averaging around 7,000 acres each.10 The bonanza farm era ended by 1900 with drought and economic decline for the wheat industry.11 The new methods used to farm the northern Plains caused a shift in resources used. Dry farming used no irrigation, and made farming on a large scale easier and more efficient. This allowed for the rise of vast monoculture wheat farms employing farmhands (not just the family owning the farm) and using large-scale equipment and machinery (such as threshers and tractors) (Fig. 3), overall making the farm process more commercial and less personal. Dry land farming techniques from the 1800s are still used on most farms in the Dakotas, and North Dakota alone produced almost 8 million acres of wheat in 2014 according to the USDA. It has been modified since Campbell’s manual, but the basis of non-irrigated farming of wheat is from Campbell. Recently in the news, organic farms in California have been turning to dry farming methods to remain productive in the droughts affecting the state, without irrigation.12 While bonanza farms are no longer in business (but some are historically preserved), “the corporation farms of the 1920’s [across the Great Plains] were largely a renewal of the idea”. Bonanza farms were the first large, monoculture farms in the wheat regions, and are commonly thought to have directly influenced commercial farming of wheat today.13 Wheat became a vastly successful national market in the early 20th century, all starting with the massive monoculture bonanza farms in the Dakotas. Notes 1. George Washington Kingsbury, History of the Dakota Territory (Ithaca: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1915), Google Books. 2. Fred A. Shannon, The Farmer’s Last Frontier: Agriculture, 1860-1897 (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1945). 3. John C. Hudson, “Agriculture,” Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, 1st ed. 4. Shannon, The Farmer’s Last Frontier, 5. 5. Lorraine J. Pellack, “Soil Surveys — They’re Not Just for Farmers,” Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship 58 (2009): doi: 10.5062/F4K935FH. 6. Shannon, The Farmer’s Last Frontier, 5. 7. John C. Hudson, “Agriculture.” 8. Ibid. 9. Hardy Webster Campbell, Campbell’s Soil Culture Manual (New York: Campbell, 1902), 5. 10. Shannon, The Farmer’s Last Frontier, 158. 11. Hiram M. Drache, “Bonanza Farming,” Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, 1st ed. 12. Brian Barth, “When the Well Runs Dry, Try Dry Farming,” Modern Farmer, July 10, 2014. 13. Shannon, The Farmer’s Last Frontier, 160. 14. David Granatstein, Dryland Farming in the Northwestern United States: A Nontechnical Overview (Washington State Cooperative Extension, 1992), Google Books. Bibliography Barth, Brian. “When the Well Runs Dry, Try Dry Farming.” Modern Farmer, July 10, 2014. http://modernfarmer.com/2014/07/well-runs-dry-try-dry-farming/. Batchelder, George Alexander. A Sketch of the History and Resources of Dakota Territory. Yankton: Press Steam Power Printing Company, 1870. Briggs, Harold E. “Grasshopper Plagues and Early Dakota Agriculture, 1864-1876.” Agricultural History 8 1934: 51-63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3739497. Campbell, Hardy Webster. Campbell’s Soil Culture Manual. New York: Campbell, 1902. Collins, Edward Elliott. “A History of Union County, South Dakota, to 1880.” Thesis, University of South Dakota, 1937. “The Commercial Side of the Dry Farming Movement.” The Thresherman’s Review 20 1911: 28-29. Accessed October 25th, 2014. Google Books. Drache, Hiram M. “Bonanza Farming.” In Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. 1st ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2004. Fargo, North Dakota: Its History and Images. “Dakota Territory Growth.” Accessed October 12th, 2014. http://library.ndsu.edu/fargo-history/?q=content/dakotaterritory-growth. Granatstein, David. Dryland Farming in the Northwestern United States: A Nontechnical Overview. Washington State Cooperative Extension, 1992. Google Books. Grant, Michael J. “Dryland Farming.” In Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. 1st ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2004. Hudson, John C. “Agriculture.” In Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. 1st ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2004. Isern, Thomas D. “Campbell, Hardy Webster (1850-1937).” In Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. 1st ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2004. Killelea, Eric. “Farmers Get Close Look at Dryland Crops.” Williston Herald, July 11, 2014. http://www.willistonherald.com/news/farmers-get-close-look-at-drylandcrops/article_5aea3552-092b-11e4-9df2-0019bb2963f4.html . Kingsbury, George Washington. History of Dakota Territory. Ithaca: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1915. Google Books. Lamar, Howard Roberts. Dakota Territory 1861-1889. London: Yale University Press, 1956. Libecap, Gary D. and Zeynep Kocabiyik Hansen. “‘Rain Follows the Plow:’ The Climate Information Problem and Homestead Failure in the Upper Great Plains, 1890-1925.” Thesis, University of Arizona, 2000. The Little Organic Farm. “A Bit of History and About the Farm.” http://www.thelittleorganicfarm.com/History.html. Lowitt, Richard. “Dry Farming.” In Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/D/DR009.html. Olmstead, Alan L. and Paul W. Rhode. “Adjusting to Climatic Variation: Historical Perspectives from North American Agricultural Development.” Thesis, Duke University, 2009. Pellack, Lorraine J. “Soil Surveys — They’re Not Just for Farmers.” Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship 58 2009. doi: 10.5062/F4K935FH. Schell, Herbert S. “Drought and Agriculture in Eastern South Dakota During the Eighteen Nineties.” Agricultural History 5 1931: 162-180. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3739326. Shannon, Fred A. The Farmer’s Last Frontier: Agriculture, 1860-1897. New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1945. Wishart, David J. “Settling the Great Plains, 1850-1930: Prospects and Problems.” In North America: The Historical Geography of a Changing Continent. 2nd ed. McIlwraith, Thomas F., ed., and Edward K. Muller, ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001.