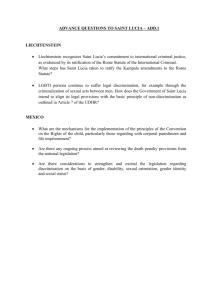

THE IMPACT OF TRADE LIBERALIZATION AND FLUCTUATIONS OF

advertisement