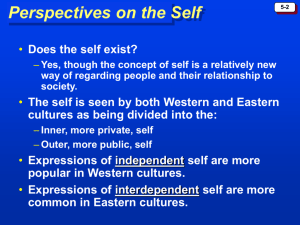

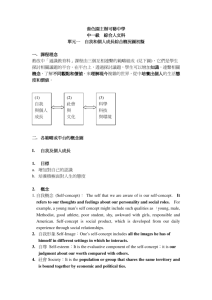

ACADEMIC SELF-CONCEPT AND POSSIBLE SELVES OF HIGH-ABILITY

advertisement