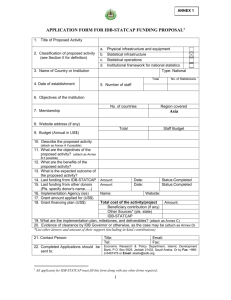

W T O

advertisement