Document 10575301

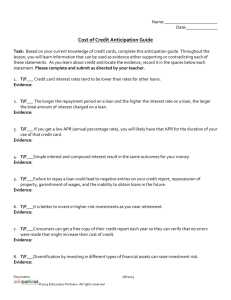

advertisement