Political Reservations and Women’s Entrepreneurship in India

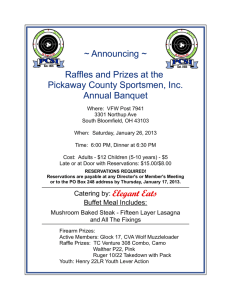

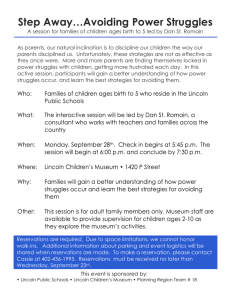

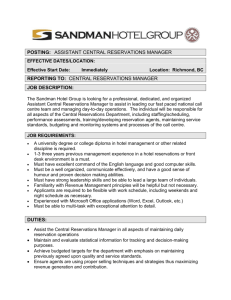

advertisement