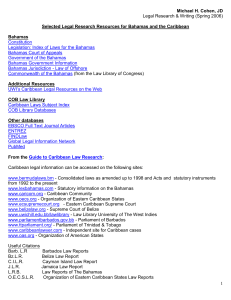

Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix

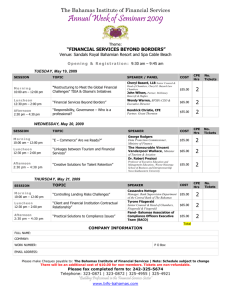

advertisement