1955

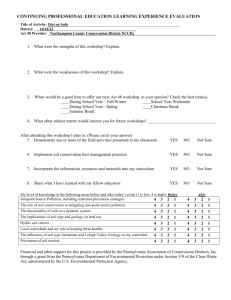

advertisement