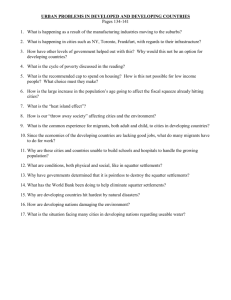

by (1986) URBAN Ecole Nationale des Travaux Public de ...

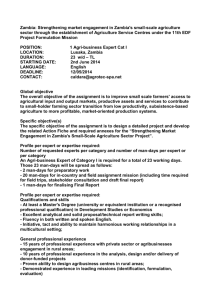

advertisement