Assessment and Permitting for Cross- : E.

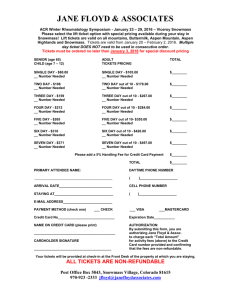

advertisement