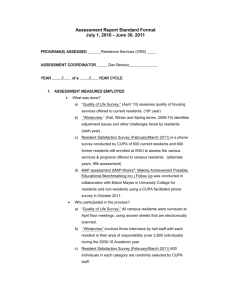

Resident Satisfaction, Resident Retention and Improved Business by 1985

advertisement