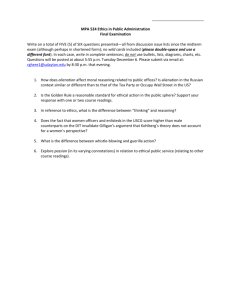

1971

advertisement