AN (1982) Pablo Jordan Architect, Universidad Catolica de Chile

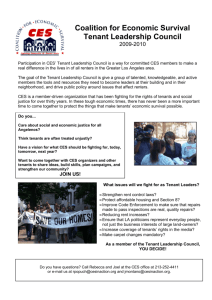

advertisement