spd

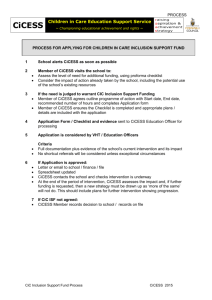

advertisement