James Andrew Carr Bachelor of Architecture Cornell University

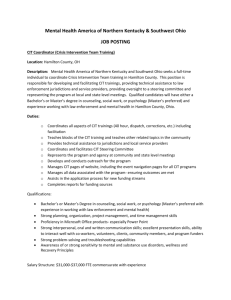

advertisement