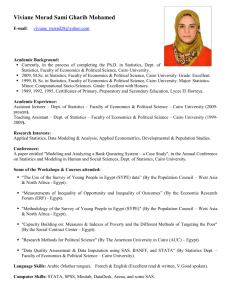

© GENESIS AND LEGACY:

advertisement