Properties of Waves Definitions wave

advertisement

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

Properties of Waves

Definitions

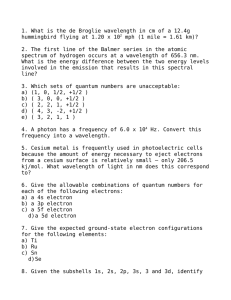

The general definition of a wave is a fluctuation in one or more properties over space or time. A

simple form of wave is a periodic oscillation. Such a wave can be described by its amplitude,

A, which is the height of each peak above the baseline (or the depth of each trough).

The wavelength is defined as the distance between peaks (or the distance between troughs) and

is usually given the symbol λ (lambda).

The frequency is defined as the number of peaks (or troughs) which pass a given point in a

given time. The common symbol for frequency is ν, and a common unit of frequency is the

Hertz (Hz), which is cycles per second.

The period, T, of a wave is the inverse of its frequency (1/ν), that is, the time interval between

peaks (or troughs) as seen from a stationary point.

A

A

time, t

distance, x

A

λ

Visible

Spectrum

The

Electromagnetic

Spectrum

Radio

Waves

0.1

Microwaves

10

A

T

Infrared

1000

10 5

Ultraviolet

Xrays

107

109

Frequency (GHz)

Gamma

Rays

10 11

Cosmic

Rays

1013

The electromagnetic spectrum

The EM spectrum

Although frequency ranges are often cited for the various forms of EM radiation, they are only a

guide. The difference between the various forms of natural radiation is really governed by the

source of the radiation rather than its frequency.

R. Ubic

II-1

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

Low-frequency radio waves are caused naturally by the reversal of electron or nuclear spins in

atoms and generally have wavelengths of more than a metre - and more than half a kilometre for

longwave. This part of the spectrum is illustrated below.

VHF TV (2-4)

VHF TV (5-6)

FM

UHF TV (7-13)

Shortwave

Radio

Longwave

0.1

AM

1

10

100

1000

Frequency (MHz)

The radio spectrum

0.1

1

U-Band

Ka-Band

Ku-Band

K-Band

X-Band

C-Band

S-Band

L-Band

UHF TV (14-83)

Microwaves

Microwave

Ovens

Microwave frequencies are usually defined as those between 300 MHz and 300 GHz, or

wavelengths of 1 mm to 1 m. Radiation of this type is excited by transitions between molecular

rotational energy levels. The microwave spectrum is broken down into various bands, as shown

below

10

100

Frequency (GHz)

The microwave spectrum.

The infrared band occurs at still higher frequencies, with wavelengths typically on the order of a

few hundred microns. Radiation in this part of the spectrum is typically produced by molecular

vibrations (phonon energy or heat). The visible spectrum is tiny by comparison, with

wavelengths ranging only from about 400 - 700 nm. Ultraviolet radiation can have wavelengths

down to just 2 nm. Both visible and ultraviolet light are produced naturally by transitions

involving valence (outer) electrons.

Far IR

0.1

1

Visible Near UV

Far UV

Middle IR

10

Near IR

Infrared, Visible,

and Ultraviolet

100

Extreme UV

1000

10 4

10 5

Frequency (THz)

The infrared, visible, and ultraviolet spectra

R. Ubic

II-2

10 6

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

With wavelengths of only 1-20 Å, x-rays are the result of transitions of more tightly held inner

electrons. It is interesting to note that in 1883 Lord Kelvin, then president of the Royal Society,

predicted that “X-rays will prove to be a hoax.” Finally, gamma and cosmic rays, with

wavelengths of less than 1 Å, are produced from very high-energy re-arrangements of nuclear

particles.

The product of wave frequency and wavelength is a constant which is equal to the speed of the

wave. In a vacuum, the speed of light (EM radiation) is c = 2.9979X108 ms-1 so:

νλ = c

Inside media other than vacuum (e.g., transparent glass), the speed of light is slowed down by a

factor equal to the square root of the dielectric constant (εr), which implies that the wavelength

decreases by the same amount (the frequency is unaffected).

Strangely, photons can be described in terms of a wave or a particle (in reality they must

therefore be neither in the conventional sense).

The energy, E, of a photon is described by

E = hν

(2.8)

where h = Planck’s constant = 6.6261 x 10-34 Js. This energy only comes in discrete packets or

quanta (hence particle representation), yet can also easily be described as a wave with frequency

ν (hence the wave representation).

The rate of flow of this energy through a unit area perpendicular to the direction of propagation

is called intensity, I

I ∝ A2

(2.9)

which is often expressed as relative intensity (e.g., Iscattered beam / Iincident beam).

Electrons as waves

Credit for discovering the electron is usually given to J.J. Thomson, who was the first to

quantify the ratio of mass to charge of what he termed negatively-charged “corpuscles.”† The

ratio he published in 1897 was 0.4 - 0.5 X 10-7 g/C (the modern value is 0.569 X 10-7 g/C);

however, Thomson did not have the whole picture.

H.A. Lorentz and A. Einstein determined in 1905 that the mass of any object varies with its

velocity, especially at very high (relativistic) speeds, according to:

†

Curiously, Thomson studiously avoided the word “electron,” which had been invented by a wily and less

respectable scientist named G.J. Stoney in 1891.

R. Ubic

II-3

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

m = mo

1− v

2

(2.10)

c2

where c is the speed of light (2.9979 X 108 m/s), mo is the rest mass of an electron (9.1091 X 10-31

kg), and v is velocity. A. Einstein published his famous equation, E = mc2, in the same year;

however, this is actually a shortened form of a longer equation valid only in the case of

stationary objects. The full relativistic equations is:

E = mc 2 = ρ 2 c 2 + mo2 c 4

(2.11)

where ρ is momentum. In the case of photons (mo = 0) then the equation reduces to:

E = ρc

(2.12)

The energy of a photon can also be defined by the photoelectric effect, which points to the

particle properties of light:

(2.13)

E = hν or E = hc/λ

where h is Planck’s constant (6.6261X10-34 Js), ν is frequency, and λ is wavelength.

Combining these two equations, we obtain:

λ = h/ρ = h/mv

(2.14)

In his 1924 Ph.D. dissertation in Paris, Louis deBroglie postulated that particles may also have

wave-like properties and that the above equation may also be true for particles like electrons as

well as for photons - the wave nature of matter.

Using this equation, Einstein’s relativistic one, and a simple energy balance, it is possible to

derive the wavelength of the electron as a function of accelerating voltage, V, only. To start, the

kinetic energy of the electron is:

KE = eV = mc 2 − mo c 2 ∴ m = mo +

eV

c2

where moc2 is the rest energy (mass energy) and e is the elemental charge of an electron

(1.6022 X 10-19 C). Setting the above two equations equal to each other and solving for v:

eV

mo

mo + 2 =

2

c

1− v

R. Ubic

and taking the inverse :

c

mo +

2

II-4

1− v

1

eV

c2

=

2

mo

c2

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

Now multiplying both sides by mo and squaring:

mo2

eV

mo + 2

c

∴v2 = c2 −

= 1− v

2

2

c2

mo2 c 2

eV

mo + 2

c

⇒ v = c2 −

2

mo2 c 2

eV

mo + 2

c

2

Now we can calculate the momentum, ρ:

ρ = mv = mo +

mo2 c 2

eV 2

c

−

2

c2

eV

mo + 2

c

(2.15)

and squaring both sides gives us:

2 2

mo c

eV 2

2

ρ = mo + 2 c −

2

c

eV

mo + 2

c

2

2 2

mo c

eV 2

eV

= mo + 2 c − mo + 2

2

c

c

eV

mo + c 2

2

2

2

2mo eV e 2V 2

eV

= c mo + 2 − mo2 c 2 = c 2 mo2 +

+ 4 − mo2

2

c

c

c

2

2m eV e 2V 2

= c 2 o2 + 4

c

c

1

= 2 2mo c 2 eV + e 2V 2

c

(

)

Therefore,

ρ=

1

2mo c 2 eV + e 2V 2

c

Now, substituting this into deBroglie's relation:

R. Ubic

II-5

(2.16)

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

λ=

h

h

= = hc 2mo c 2 eV + e 2V 2

mv ρ

(

)

−1

2

(2.17)

The wave nature of electrons makes possible interference and diffraction. The eventual

discovery of electron diffraction was made jointly by C.J. Davisson and L.H. Germer at Bell

Labs, USA and G.P. Thomson (son of J.J.) and A. Reid in the UK in 1927. Both teams used Ni

crystals in their experiments, and Davisson and Thomson later shared the Nobel Prize for their

discovery in 1937.

The Bohr Atom

Atoms are, of course, made up of a positively charged nucleus

surrounded by a negatively charged cloud of electrons. An early

emodel of the atom which combined elements of classical and

+

quantum mechanics was that of Bohr (1913). Consider the

e

2

e

simple hydrogen atomic model shown. The electron, which has

r

2

a charge of -e (e = 1.6022x10-19 C) and rest mass of mo =

4πε o r

9.1094x10-31 kg, revolves around the nucleus, which consists of

-27

Bohr model of the hydrogen a single proton of charge +e and mass m = 1.6726x10 kg, in a

circular orbit of radius r and with a velocity v. The stability of

atom

the orbit requires equilibrium between the attractive Coulombic

force on the electron and the centrifugal force. This balance of forces must satisfy equation 2.1.

mv 2

r

mv 2

e2

=

r

4πε o r 2

(2.1)

where εo is a constant introduced by Coulomb’s Law called the permittivity of free space and is

equal to 8.854x10-12 F/m. The total energy of the electron W is the sum of its kinetic energy and

its potential energy (Wp) due to the Coulomb field of the proton. Defining the potential energy

for r → ∞ as zero, equation 2.2 is obtained.

W=

1

2

2 mv −

e2

4πε o r

(2.2)

The minus sign indicates that the electron has less energy in the orbit r than it would at r = ∞.

Now, substituting equation 2.1 into equation 2.2 one arrives at equation 2.3.

e2

e2

−e 2

W=

−

=

(2.3)

8 πε o r 4πε o r 8 πε o r

Equation 2.3 states that the electron is bound to the nucleus, and the energy required to excite it

away is the positive quantity -W. W decreases as r decreases, but, of course, that is not to imply

negative energy!

Bohr realised that this classical model of the atom would be unstable because the electron’s

energy would dissipate, sending the electron crashing into the nucleus. According to classical

R. Ubic

II-6

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

electromagnetic theory, an electric charge e undergoing harmonic oscillation with angular

frequency ωo (rad/s)† and amplitude xo along a line, its coordinate x being given by the equation x

= xocosωot, where t is time, loses energy W by emitting radiation (light) at the rate

−

dW ω 4o e 2 xo2

=

dt

3c 3

An electron in a circular orbit in the xy plane is equivalent to a linear oscillator along the x-axis

and one along y, and should consequently radiate twice as fast. This energy loss is a simple way

of understanding Bohr’s dilemma. In order to retain the orbit’s stability, Bohr suggested that the

electron can only radiate energy of a certain size. He postulated that only those circular orbits

are stable for which the angular momentum is an integer multiple of h/2π, where

h = 6.6261x10-34 Js is Planck’s constant. Mathematically, this requirement takes on the form of

equation 2.4.

mvr = nh 2π

n = 1,2,3...

(2.4)

Substituting equation 2.4 into equation 2.1, one obtains an expression for the radii of all the

allowed circular orbits in hydrogen.

ε oh2 2

rn =

n ≈ 0.529n 2 Å

2

πme

(2.5)

Now, combining equations 2.3 and 2.5 one obtains an expression for the binding energy for

electrons in various circular orbits n.

− e 2 πme 2 − me 4 1

−13.6

= 2 2 2 ≈

W =

eV

2

2

n2

8 πε o ε o h n 8 ε o h n

(2.6)

Quantum electron transitions

According to equation 2.6, when n = 1, the electron is bound to the nucleus with 13.6 eV (1 eV =

1.6022x10-19 J). It can be further deduced that as n increases (r increases), less energy is

required to strip the electron from the nucleus. One final postulate to complete this view of the

atom states that the transition of an electron from one energy level Wn1 to another Wn2 is

accompanied by the emission or absorption of electromagnetic radiation of frequency ν such

that:

hν = Wn2 − Wn1

Thus, the energy involved in electronic transitions is quantized.

approximation, n determines the energy of the electron.

†

The frequency ν in Hz is simply given by ν = ωo/2π.

R. Ubic

II-7

(2.7)

To a very good first

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

The idea of an atom consisting of electrons in quantised energy states was further developed by

Schrödinger and Heisenberg (1924). Their wave mechanical treatment of the atom replaced

electrons in circular orbits with charge distributions of various shapes. The charge density

(C/m2) associated with the single ground-state electron in hydrogen is:

ρ (r ) = (e πr12 )e

−2 r

r1

(1.8)

where r1 = 0.529 Å (the radius of the first Bohr orbit). This density is highest for r = 0 and goes

to zero when r → ∞. The total charge on a sphere of radius r is given by the product of the

charge density ρ(r) and the surface area of the sphere (4πr2). This product reaches a maximum

for r = r1, indicating that the maximum charge distribution in the ground state occurs at a

distance from the nucleus equal to the first Bohr radius.

Erwin Schrödinger’s (1887 - 1961) three-dimensional wave equation,

∇2Ψ +

2m

(W − W p )Ψ = 0

h2

h = h / 2π

(1.9)

describes the statistical distribution of electrons around a nucleus (W = total energy,

Wp = potential energy). In spherical coordinates, its solution is of the form:

Ψ(ρ, θ, φ) = R(r )Θ(θ)Φ(φ)

and |Ψ|2dV is the probability of finding an electron in volume element dV. The solution involves

four constants. The first, n, is the principal quantum number. The second, l, sometimes called

the azimuthal, angular momentum, or orbital quantum number, determines the angular

momentum of the electron. Its value can be 0,1,2,...(n-1). The orbital angular momentum is

1

{l (l + 1)} 2 h . The component of angular momentum along a given direction, usually defined as

that of an applied magnetic field, must be a multiple of h , and the multiplying factors are ml, the

third or magnetic quantum number. It can assume any integer value between -l and +l. The

fourth and final quantum number describes the intrinsic angular momentum of the electron, like

that of a spinning top, and is usually called the spin quantum number, s. The solution of the

equation requires that s = ±½, making it the only non-integer quantum number. The total angular

1

momentum (orbital plus spin) is then equal to { j ( j + 1)} 2 h , where j = l ± s and is generally

called the total angular momentum quantum number.

The principal quantum number is an indication of the electron energy, and the group of states

corresponding to a given value of n is referred to as a shell of electrons. The n = 1, 2, 3, 4...

states correspond to the K, L, M, N... shells.† The angular momentum quantum number, l,

†

The naming of these shells is an historical accident. Between 1905 and 1910, Charles G. Barkla discovered that

elements emit characteristic x-ray radiation of two kinds, differing in their penetrating power. After having used the

letters A and B, in 1911 he decided to assign K to the more penetrating and L to the less penetrating x-rays in order

R. Ubic

II-8

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

describes the shape of the electron orbital. The l = 0 orbital is called the s (sharp) orbital and as

has already been seen, it describes a spherical charge distribution. The l = 1 or p (principal)

orbital consists of six lobes symmetrically arranged about the nucleus along ±x, ±y, and ±z

directions. There are ten l = 2 or d (diffuse) orbitals and fourteen l = 3 or f (fundamental)

orbitals, all of which are also lobes arranged in a complicated way about the nucleus. The names

of the orbitals are relics of the nomenclature used in the classification of spectral lines. The

Pauli Exclusion Principle states that no two electrons within an atom can have the same four

quantum numbers. The outer electron states in atoms which are bonded together overlap, thus

broadening the energy levels into bands (valence band and conduction band).

In general, each electron shell can take 2n2 electrons; however, the way in which the various

orbits fill is not as trivial as it may first seem. Lower-energy shells do not always fill before

higher-energy ones. The group of elements for which parts of an inner shell are not occupied

are called transition elements. In general, the order in which orbitals are filled is illustrated in

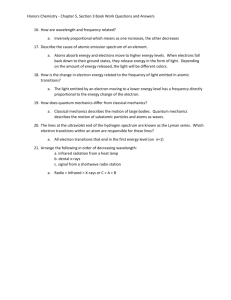

Fig. 1.6. Following the arrows across and down, the filling sequence is

1s,2s2p,3s3p,4s,3d,4p,5s,4d,5p,6s...

Occasionally, hybrid orbitals are created, as is the case with carbon or boron. The electronic

structure of carbon is: 1s2,2s22p2, meaning the 1s (n = 1, l = 0) orbital is completely filled with 2

electrons, as is the 2s (n = 2, l = 0) orbital, and the 2p (n = 2, l = 1) orbital is only 1/3 filled with 2

of a possible 6 electrons. This structure would give carbon two different kinds of bonds;

however, it is well known that carbon forms four tetrahedrally arranged bonds of equal strength.

1s

2s

2p

3s

3p

3d

4s

4p

4d

4f

5s

5p

5d

5f

6s

6p

6d

6f

FIGURE 1.6 Schematic of the order in which electron orbitals are filled (excluding hybrids)

The atom does this by forming hybrid orbitals - it combines the 2s and 2p orbitals into 2sp

orbitals, making the outer electrons 2sp4, therefore all equivalent. The most stable configuration

for such orbitals tends to maximise their spatial separation, creating four orbitals each 109.47°

to leave other letters available for more penetrating radiation which he thought would be discovered. He soon found

M and N radiation, but characteristic x-rays more penetrating than K were, of course, never discovered.

R. Ubic

II-9

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

from the other - a regular tetrahedron. Similarly with boron, the 2s22p1 electrons are combined

into 2sp3 whose maximum separation results in a trigonal planar configuration.

Atoms prefer full or half-full shells, so filling sequences are sometimes shifted in order to

achieve this. In addition, outer shells with single electrons are very unstable, and such atoms are

readily positively ionised (e.g., Na, K, and the other alkali metals). Similarly, atoms with outer

shells deficient by a single electron readily ionise negatively in order to complete them (e.g., F,

Cl, and the other halogens).

An electron in its normal energy level is said to be in the ground state. Similarly, an atom with

all its electrons in the ground state is also in the ground state.

There are two sets of terminology in use to describe the localized energy levels of electrons. The

spdf notation described above is traditional and very wide-spread. The alternative nomenclature

is that recommended by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).

spdf Notation

In the spdf notation, electron states are referred to by a number equal to the principle quantum

number, n, followed by a letter (s, p, d, or f) corresponding to the orbital shape described by the

angular momentum quantum number, l. A superscript is used to indicate the number of electrons

in that orbital.

IUPAC Notation

In the IUPAC notation, a letter (K, L, M...) is assigned to each energy shell (1, 2, 3...) and a

subscript number, which is related to both l and ml quantum numbers, is used to indicate specific

electron states. The number is 1 if l = 0; 2 if l = 1 and ml = 0; 3 if l = 1 and ml = ± 1; etc. In the

case of n = 1 (K), no subscript number is used.

Transitions - Rules

We have already seen (§ II.E.3.f) how an inner-shell electron can be liberated from its atom by a

high-energy electron, resulting in an outer electron dropping into its place and the release of a

photon of x-ray energy. This process is called an electron transition; however, not all possible

electron transitions are allowed by quantum mechanics. There are essentially four selection rules

governing which transitions are allowed.

R. Ubic

a.

∆n < 0

The principle quantum number, n, of the electron must be reduced in the

transition.

b.

∆l = ± 1

The angular momentum quantum number, l, must change by ± 1 (never 0).

This rule does not apply to Auger electron emission.

c.

∆ml = 0 or ± 1

d.

∆s = 0

This rule does not apply to Auger electron emission.

II-10

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

R. Ubic

Siegbahn

Line

Kα1

Kα2

Kβ1

Kβ I2

IUPAC

line

K-L3

K-L2

K-M3

K-N3

Siegbahn

Line

Lα1

Lα2

Lβ1

Lβ2

IUPAC

line

L3-M5

L3-M4

L2-M4

L3-N5

Siegbahn

Line

Mα1

Mα2

Mβ

Mγ

IUPAC

line

M5-N7

M5-N6

M4-N6

M3-N5

Kβ II2

Kβ3

Kβ I4

K-N2

Lβ3

L1-M3

Mζ

M4,5-N2,3

K-M2

K-N5

Lβ4

Lβ5

L1-M2

L3-O4,5

Kβ II4

K-N4

Lβ6

L3-N1

Kβ 4x

K-N4

Lβ7

L3-O1

Kβ 5I

K-M5

Lβ '7

L3-N6,7

Kβ 5II

K-M4

Lβ9

L1-M5

Lβ10

Lβ15

Lβ17

Lγ1

Lγ2

Lγ3

Lγ4

Lγ’4

Lγ5

Lγ6

Lγ8

Lγ’8

Lη

Ll

Ls

Lt

Lu

Lv

L1-M4

L3-N4

L2-M3

L2-N4

L1-N2

L1-N3

L1-O3

L1-O2

L2-N1

L2-O4

L2-O1

L2-N6(7)

L2-M1

L3-M1

L3-M3

L3-M2

L3-N6,7

L2-N6(7)

II-11

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

The last two rules can almost always be satisfied, so it’s the first two rules which are the most

useful to keep in mind.

The Siegbahn notation is widely used to describe electron transitions, but it is not entirely

systematic. Transitions are denoted by a letter (K, L, M...), which corresponds to the shell into

which the higher-energy electron has dropped, followed by another letter (sometimes Greek)

related in a non-systematic way to the higher-energy state, followed by another number. The

IUPAC system is more systematic. Transitions are denoted simply by indicating first the final

state of the electron followed by its initial state. In the case of unresolved lines, such as K-L2

and K-L3, the recommended IUPAC notation is K-L2,3.

Elastic interactions of radiation (waves) with matter

Reflection - the redirection of a beam incident upon a reflective surface away from that surface,

at an angle equal to the incident angle.

Law of reflection is derived from Fermat's principle (light follows path of least time).

Both angles are measured with respect to the normal to the surface.

Smooth surface (e.g., a mirror), easy

Rough surface, multiple surface orientations (roughness) yield multiple reflection angles

and thus cause severe light scattering (why we polish specimens).

Io

Ir

θi θr

R. Ubic

Law of Reflection:

θi = θr

II-12

Io

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

Refraction - Light incident upon a surface will in general be partially reflected and partially

transmitted.

Bending of a wave when it enters a medium where its speed is different.

A wave bends when it passes from a fast medium (low µ) to a slow medium (high µ).

The bend is toward the normal to the boundary between the two media, and the amount

of bending depends on the indices of refraction (µ)

θ1

Snell’s Law:

Slow

medium

θ2

µ1 sin θ 2

=

µ 2 sin θ1

µ = cv

Rayleigh Scattering

Scattering of light off air molecules and particles up to about a tenth of the wavelength of the

light.

I = Io

8π 4 N α 2

(1 + cos 2 θ)

4 2

λR

θ

I = scattered intensity at a distance R from N dipole scatterers much smaller than the

wavelength, λ, with polarisability α.

Strong wavelength dependence which makes the sky blue.

R. Ubic

II-13

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

Inelastic Scattering Events

Compton Scattering

The scattering of photons from charged particles is called Compton scattering after Arthur

Compton who was the first to measure photon-electron scattering in 1922. When the incoming

photon gives part of its energy to the electron, then the scattered photon has lower energy and

accordingly lower frequency and longer wavelength.

At a time when the particle (photon) nature of light was still being debated, Compton gave clear

and independent evidence of particle-like behaviour and was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1927

for the discovery of the effect named after him.

The change in wavelength of the x-ray can be calculated by simply applying the conservation of

energy and momentum to the collision between the photon and electron; however, before

attempting this derivation, it is useful to review some basic concepts.

Energy of a photon with frequency ν is:

Momentum of a photon with wavelength λ:

E = hν

ρ = E/ c = h ν / c = h / λ

Energy of a particle with mass m and velocity v:

E = mc2 =

mo c 2

1− v

=

2

(ρc )2 + (mo c 2 )2

c2

With these definitions in mind, the energy balance is:

hυ i + m o c 2 = hυ f +

(ρ e c )2 + (mo c

2

)

2

which can be re-written as:

(ρ e c )2

= h 2 ν i2 + h 2 ν 2f + 2hν i mo c 2 − 2hν f mo c 2 − 2h 2 ν i ν f

Now, considering the conservation of momentum,

R. Ubic

II-14

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

v

v v

ρe = ρi − ρ f

This equation can be squared by invoking the scalar product of vectors (dot product):

v v

v v

v v

ρ e • ρ e = (ρ i − ρ f ) • (ρ i − ρ f )

v v

v

v

v v

ρ e2 = (ρ i • ρ i ) + (ρ f • ρ f ) − 2(ρ i • ρ f

2

e

2

i

)

2

f

ρ = ρ + ρ − 2ρ i ρ f cos θ

which, by multiplying both sides by c2 and making the substitution ρ2c2 = h2ν2, can also be rewritten as:

(ρ e c )2

= h 2 ν i2 + h 2 ν 2f − 2h 2 ν i ν f cos θ

Now, by equating these two expressions for (ρec)2, one obtains:

h 2 ν i2 + h 2 ν 2f + 2hν i mo c 2 − 2hν f mo c 2 − 2h 2 ν i ν f = h 2 ν i2 + h 2 ν 2f − 2h 2 ν i ν f cos θ

2h 2 ν i ν f − 2h 2 ν i ν f cos θ = 2hν i mo c 2 − 2hν f mo c 2

2h 2 ν i ν f (1 − cos θ) = 2hmo c 2 (ν i − ν f

)

Finally, divide both sides by 2hν iν f mo c to obtain the Compton formula:

h

(1 − cos θ) = λ f − λ i = ∆λ

mo c

The shift in the wavelength increases with scattering angle. The constant in the formula

(h/moc) = 0.0243 Å for an electron and is called the Compton wavelength for the electron.

Fluorescence

Fluorescence is the absorption of light at one wavelength and its re-emission in any direction at a

longer wavelength. When a photon is incident on an atom, it may eject an electron from an inner

shell. This electron is called a photoelectron. This excited atomic state relaxes by filling the

inner shell with an outer electron whilst simultaneously releasing a photon characteristic of the

atom which produced it. If the relaxation occurs via an intermediate excited state, there is a

delay in the emission of the photon and the process is termed phosphorescence.

hv2

hv1

R. Ubic

II-15

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

Absorption

The penetration depth or mean free path of the incident beam determines the depth and volume

of material that will be sampled. In many cases the radiation detected is a different type to that

used in the probe (e.g., EDS and XPS).

Visible light is used mainly to obtain a visual image of the surface of a material, although it can

also be used to probe the optical properties of a (usually transparent) specimen. Ultraviolet

radiation (3.1 ≤ E ≤ 620 eV) can be used to investigate the electron distribution in surface atoms.

After visible light, x-rays (620 eV < E ≤ 12.4 keV) are the next most utilised part of the spectrum

to characterise materials. They are useful for probing the atomic arrangement (crystallography)

of matter.

The penetration distance varies with wavelength and material and is typically several microns for

x-rays but much shorter for electrons. The linear absorption coefficient, µ, which increases

with atomic number, determines the depth of penetration according to:

I = I o exp(−µx)

where I is the intensity of radiation transmitted through the material, Io is the intensity of

radiation originally incident, and x is the thickness of the material. For a substance with mass

density ρ, the mass absorption coefficient is µ/ρ and is independent of the physical state of the

material (solid, liquid, or gas), and the equation can be re-written as:

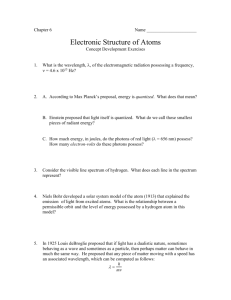

Mass Absorption Coefficient (cm2/g)

I = I o exp[−( µ ρ )ρx]

Wavelength (Å)

Absorption coefficients (µ/ρ) of Pb showing K and L absorption edges

When x-ray photons of wavelength 0.4 Å are incident on a sheet of Pb, the absorption coefficient

is about 30 cm2/g. As the wavelength decreases (frequency increases), the absorption coefficient

decreases because photons of higher energy pass more easily through a material. When the

wavelength is reduced to just below the critical value, which is 0.14088 Å for Pb, the absorption

R. Ubic

II-16

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

coefficient suddenly rises by a factor of about 5. Photons now have sufficient energy to knock K

electrons out of the atoms. True K absorption is now occurring and a large fraction of the

incident energy is converted into K fluorescent radiation and kinetic energy of ejected

photoelectrons. The five-fold increase in µ/ρ means a tremendous decrease in transmitted

intensity because of the exponential dependence of I. If the percentage of photons transmitted in

a given Pb sheet is 0.1 for x-rays with wavelengths just longer than 0.14088 Å, it is only 2.2X10-5

for wavelengths just shorter. The value of 0.14088 Å is called the K absorption edge for Pb.

Three closely spaced L edges exist at longer wavelengths, five M edges, etc. Each of these

discontinuities marks the wavelength of photons which have just sufficient energy to eject an L,

M, N, etc. electron from the atom.

Absorption of x-rays occurs in two distinctly different ways, by scattering and by true

absorption, and these two processes together make up the total absorption measured by µ.

Compton scattering of x-rays occurs in all directions and thus reduces the number of photons in

the transmitted beam. True absorption is an inelastic process caused by the production of

photoelectrons and fluorescent radiation.

Absorption of x-rays is important for a number of reasons. Firstly, it obviously plays a role in

shielding and screening of x-ray producing equipment. Secondly, implantable biomaterials are

visible in x-ray images because of their radiopacity, that is, they are opaque to x-rays. The level

of opacity required is equivalent to 1mm of aluminium. Third, absorption has a role in filtering

x-rays, which will be covered in more detail later on.

R. Ubic

II-17

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

Raman effect

The Indian physicist Sir Chandrasekkara Venkata Raman (1888-1970) discovered in 1928 that

when visible light is scattered, some of the scattered light undergoes shifts in wavelength. He

based his theory on an analogous effect observed in x-rays. Assuming that the x-ray scattering

of the unmodified type observed by Compton corresponds to the normal or average state of the

atoms and molecules, while the modified scattering of altered wavelength corresponds to their

fluctuations from that state, Raman postulated and eventually proved that two types of scattering

should also be observed in the case of visible light. The first (Rayleigh scattering) should be

due to the normal optical properties of the atoms or molecules, the second (Raman scattering)

representing the effect of their fluctuations from their normal state. While on average the

position of an atom in a crystal is known by its symmetry, these tiny vibrations break that

symmetry at any given instant, and can thus lead to Raman scattering. While most scattered light

retains the wavelength of the incident light, a small fraction is scattered at altered frequencies.

The Raman effect lent support to the photon theory of light and furnished a valuable tool in

probing the nature of matter. He was honoured for the discovery with the Nobel Prize for

physics in 1930.

The development of vibrational infrared (IR) absorption spectroscopy and Raman

spectroscopy after World War II was a major step in applying spectroscopy to determine

molecular structure. The IR spectrum and complementary Raman scattering spectrum provide

information about vibrations of atoms with respect to each other.

Symmetrical stretching

(breathing)

Asymmetrical stretching

+

In-plane deformation

(scissoring)

+

Rocking

+

-

Out-of-plane deformation Out-of-plane deformation

(wagging)

(twisting)

Matter is composed of atoms bonded together where the bond lengths are determined by a

balance between attractive, long-range Coulombic forces and short-range repulsive interactions.

Imagining each atom as a solid ball and the bonds as springs, one can imagine vibrations in the

lattice which correspond to thermal energy. Indeed, the structure will have certain natural

frequencies where resonance occurs. Most radiation at these frequencies will be absorbed; and,

as we have already seen, these frequencies lie in the infrared spectrum. Using these frequencies

to characterise a material is called infrared (IR) spectroscopy. Vibrations in the direction of the

R. Ubic

II-18

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

bond are called stretching vibrations while those normal to the bond are called bending or

deformation vibrations.

Molecules that consist of many atoms have very complex vibrations, but all vibrations of the

whole can be reduced to a superposition of a finite number of normal modes of vibration. In

each normal mode, all the atoms are assumed to vibrate with the same frequency and in phase.

The simple CO2 molecule has four such modes. In a more complicated molecule like acetone

(CH3COCH3), with ten atoms, 24 modes are possible. In general, an N-atom molecule (or

primitive unit cell) has 3N-6 modes of vibration (a linear N-atom molecule has 3N-5 modes).

Fortunately, not all vibrational modes are important for identifying molecular structures. For

example, the most distinctive vibration of the acetone molecule is that of the carbonyl (C=O)

group; the rest of the molecule can be regarded as fixed in space. The absorption frequency of

the carbonyl group is not strongly influenced by the rest of the molecule, so that most

compounds which contain this group display a similar band in their IR or Raman spectra, or

both, at frequencies between 5.0 and 5.6x1013Hz. It is common to express these frequencies in

terms of the wavenumber, or number of wavelengths per centimetre. The wavenumber is

simply the inverse of wavelength (1/λ). The resultant wavenumber typically has units of cm-1,

but is often referred to (somewhat incorrectly) as frequency in the literature.

The existence of such group frequencies makes IR and Raman spectroscopy valuable analytical

tools. The most important and exploited group frequencies are those corresponding to light

hydrogen atoms vibrating with respect to the rest of the molecule, the C-C bonds in diamond,

and double and triple bonds.

Raman spectroscopy

As a first approximation, it is possible to separate the kinetic energy of a molecule into three

components associated with the rotation of the molecule as a whole, the vibrations of the

constituent atoms, and the motion of the electrons in the molecule. The justification for this

separation lies in the fact that the velocity (and hence kinetic energy) of the electrons about a

nucleus is much greater than the velocity of the vibrating nuclei, which in turn is much greater

than the velocity of molecular rotation. If a molecule is placed in an electromagnetic field such

as that carried by a photon of light, a transfer of energy from the field to the molecule will occur

only when Bohr's frequency condition is satisfied:

∆E = hν

where ∆E is the difference in energy between two quantized states, h is Planck's constant, and ν

is the frequency of light. If

∆E = E' ' − E'

( E' ' > E' )

where E'' and E' represent the energy associated with different quantum states S'' and S',

respectively, then the molecule absorbs radiation when it is excited from S' to S'' and emits

radiation when it reverts from S'' to S'.

R. Ubic

II-19

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

Because rotational energy levels are relatively close together, transitions between these levels

involve energies of low frequencies. Pure rotational spectra occur in the range between 1 cm-1

to 100 cm-1 and are observed in the microwave and far infrared region. The quantum separation

of vibrational energy levels is greater, and those transitions involve energies of higher frequency.

Pure vibrational spectra are observed in the range from 100 to 10,000 cm-1, which appear in the

infrared region.

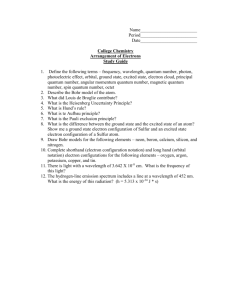

Although vibrational spectra are observed experimentally as IR or Raman spectra, the physical

origins of these two types of spectra are quite different. IR spectra originate in transitions

between two vibrational levels of the molecule in the electronic ground state and are usually

observed as absorption spectra in the infrared region. On the other hand, Raman spectra

originate in the electronic polarization caused by ultraviolet or visible light. Put another way, IR

spectra arise due to a change in the electronic dipole moment during the vibration, which has a

frequency νν; whereas Raman spectra arise due to a change in the polarizability of the molecule

during the vibration. If a molecule is irradiated by monochromatic light of frequency ν, then,

because of electronic polarization induced in the molecule by the incident photon, light of

frequency ν (Rayleigh scattering) as well as of ν±νν (Raman scattering) is emitted. Thus the

vibrational frequencies are observed as Raman shifts from the incident frequency ν in the

ultraviolet or visible regions.

ν4

ν1

Intensity

ν2

FTIR

Raman

ν4

ν3

600

800

1000

1200

1400

1600

-1

Wavenumber (cm )

Origin of IR and Raman spectra

Although Raman scattering is weaker than Rayleigh scattering by a factor of 10-3 to 10-4, it is

possible to observe the effect by using a strong exciting source. The development of lasers has

made it possible to choose any number of such sources, and typical laser lines used include Kr+

(647.1nm, 15,454cm-1, red), He-Ne (632.8nm, 15,803cm-1, red), Ar+ (514.5nm, 19,436cm-1,

green), and Ar+ (488.0nm, 20,492cm-1, blue).

R. Ubic

II-20

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

The origin of Raman spectra, though quantum mechanical, can be explained by classical theory

by considering a light wave of frequency ν with an electric field strength E. According to EM

theory, E fluctuates at frequency ν:

E = E o cos2πνt

where Eo is the amplitude. This, then, describes the electric field associated with a photon of

light. If a simple diatomic molecule is irradiated by this light, an induced dipole moment P is

generated in the molecule and is given by:

P = αE = α Eo cos2πνt

where α is a proportionality constant called the polarizability.* Now, if the molecule is vibrating

with frequency νν, then the net displacement of the atomic nuclei from their equilibrium

positions is given by:

q = qo cos 2πννt

For small vibrational amplitudes qo, α is a linear function of q, so:

δα

α = αo +

q

δq o

where αo is the polarizability at the equilibrium position and (δα/δq)o is the rate of change of α

with respect to q evaluated at the equilibrium position. All that is left is to combine equations

and collect terms to obtain an expanded expression for P.

P = αEo cos 2 πνt

δα

q Eo cos 2 πνt

= αo +

δq

o

δα

qEo cos 2 πνt

= αoEo cos 2 πνt +

δq o

δα

qo cos 2 πννtE o cos 2 πνt

= αoEo cos 2 πνt +

δq

o

δα

= αoEo cos 2 πνt +

qo Eo cos 2 πνt cos 2 πννt

δq o

Here, P has been simplified into linear form. In reality, P=αΕ + βΕ2 + γΕ3 . . . where β and γ, called the

hyperpolarizability, are usually ignored due to their small contribution to P.

*

R. Ubic

II-21

MSE 421/521 Structural Characterization

Finally, a little trigonometric manipulation suffices to show that

cos a cos b = 12 [cos( a + b) + cos( a − b )]

δα

qo Eo {cos[ 2 π( ν + νν )t ] + cos[2 π ( ν − νν ) t ]}

∴ P = αoEo cos 2 πνt + 12

δq o

The first term in this equation describes an oscillating dipole which radiates light of frequency ν,

which simply corresponds to Rayleigh scattering. The second term describes the Raman effect,

that is, light which is scattered at frequencies ν+νν (anti-Stokes) and ν-νν (Stokes). It is also

clear that if

( )

δα

δq o

= 0 then the second term becomes zero and there is no Raman effect;

therefore, the primary requisite for a molecular vibration to be Raman active is that the electronic

polarizability must change during the vibration.

R. Ubic

II-22