Household Options and Limitations in Marginal Upland Areas in Java:... Observations in a Small Village in West Java and Beyond

advertisement

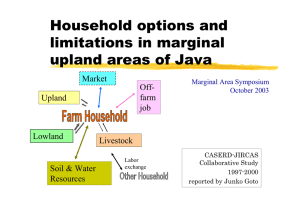

Household Options and Limitations in Marginal Upland Areas in Java: Field Observations in a Small Village in West Java and Beyond Junko Goto Independent regional planning researcher, 4-9-25, Higiriyama, Konan-ku, Yokohama, Japan, Email: jgoto999@yahoo.co.jp ABSTRACT Java, Indonesia, is usually characterized by its rich natural resource endowment and cultural heritages. Marginal areas, however, do exist in this central island of Indonesia. This report is based on a socio-economic investigation of a small upland village in West Java, where a banana-based farming systems research took place to assist a small farmer development project called P2RT in the late 1990s. This survey was part of JIRCAS-CASERD collaborative research initiated in 1997. Our survey of fifty-one households in 1998 revealed that, on the average, a farmer operated 0.20 ha of lowland in 1.35 parcels and 0.72 ha of upland in 2.06 parcels, i.e. a total of 0.92 ha in 3.41 parcels. Those parcels were located mostly inside the village and were usually owner-operated. Although lowland comprised only one fourth or less in each farmer’s operation, lowland rice requires roughly half of the labor input and rice was very important for household subsistence. Lowland operation in upland areas is usually dependent on natural rainfall and intensive human labor input. Technical irrigation and small tractors which are common in the lowland area is still beyond reach. Yet, because of government emphasis to bring small and poor farmers into agribusiness development, production of upland crops was encouraged. Local farmer groups were stimulated as a vehicle for extension at first, and subsequently for further economic cooperation at the community level. Upland crops in the area included banana, corn, peanuts, soybean, cassava, and chili, among which banana and chili were the main cash earners. Clove, palm sugar, and small livestock sales also contributed to the farmers’ income. Prior to this project, main income sources were daily wages from plantation or remittances from family members working in large cities or abroad. In the mid-1990s, plantation went bankrupt and the state company that succeeded the land allowed local farmers to cultivate. After a few years of market-oriented operation, however, agricultural income was still a small portion of household sustenance. Based on our survey, we classified farmers (households) into the following five categories: progressive farmers, subsistent farmers, barely subsistent farmers, part-time farmers, and households with remittance incomes. It is apparent that not every household can try to become the progressive farmer type. In addition to the difficulties associated with the remoteness and unfavorable soil and water conditions in the area, farmers have to cope with the macro-economic difficulty of rising input cost and depressed agricultural market. Differences in priority between farmers (if we can call them farmers) and the research and extension staff were also obvious from our field experience. Small farmer development requires rethinking of priority and measurement of progress.