Assessing the Effect of Architectural Design on Real Estate Values:

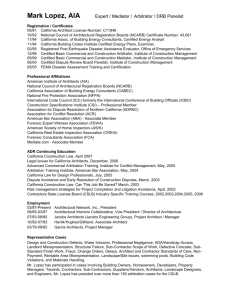

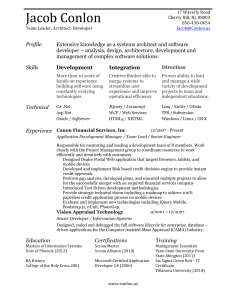

advertisement