Tax Expenditure Analysis and Housing Policy Reform J.D.

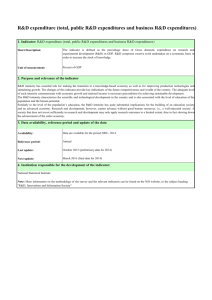

advertisement